Then Lee Robinson sat down and spent 344 agent requests and around $260 to migrate the content and setup to markdown files, GitHub, Vercel, and a vibe-coded media management interface.

He did a great write-up of the process on his blog. He was classy and didn’t name us.

Of course, when a high-profile customer moves off your product and the story resonates with builders you respect, you pay attention.

The weird twist here is that we sort of agree with Lee’s take. He has a lot of great points. The conversation around complexity and abstractions that a headless CMS brings reflects real frustration. The way things have been done for the past decade deserved criticism.

But Lee’s post doesn’t tell the full story. We see what people are trying to solve when it comes to content every day. We live and breathe this CMS stuff. So let us add some context.

The headless CMS industry built complexity that didn’t deliver proportional value for many. This is true.

Preview workflows are clunky. Draft modes, toolbar toggles, account requirements just to see what your content looks like before it goes live. Having to add data attributes everywhere to connect front ends with backend fields feels unnecessary. Real friction for something that feels it should be simple.

Auth fragmentation is annoying. CMS login. GitHub login. Hosting provider login. Three systems to get a preview working.

Their CDN costs was largely caused by hosting a video from our file storage. It’s not an ideal way to host videos in front of Cursor’s massive audience. We should have made it more obvious that there are better and cheaper ways, like using the Mux plugin.

332K lines of code was removed in exchange for 43K new ones. That sounds a great win. We love getting rid of code too.

And here’s the one that actually matters: AI agents couldn’t easily reach content behind authenticated APIs. When your coding agent can grep your codebase but can’t query your CMS, that’s a real problem. Lee felt this friction and responded to it. (We did too, and the new very capable MCP server is out).

These complaints are valid. We’re not going to pretend otherwise.

Here’s the thing though. Read his post carefully and look at what he ended up with:

- An asset management GUI (built with “3-4 prompts,” which, to be fair, is impressive)

- User management via GitHub permissions

- Version control via git

- Localization tooling

- A content model (markdown frontmatter with specific fields)

These are CMS features. Distributed across npm scripts, GitHub’s permission system, and Vercel’s infrastructure.

The features exist because the problems are real. You can delete the CMS, but you can’t delete the need to manage assets, control who can publish what, track changes, and structure your content for reusability and distribution at scale.

Give it six months. The bespoke tooling will grow. The edge cases will multiply. Someone will need to schedule a post. Someone will need to preview on mobile. Someone will want to revert a change from three weeks ago and git reflog won’t cut it. The “simple” system will accrete complexity because content management is complex.

Even with agents. Who were mostly trained within the constraints of these patterns.

Lee’s model is clean: one markdown file equals one page. Simple. Grep-able.

This works until it doesn’t.

The content === page trap

What happens when your pricing lives in three places? The pricing page, the comparison table, the footer CTA. In markdown-land, you update three files. Or you build a templating system that pulls from a canonical source. At which point you’ve invented content references. At which point you’re building a CMS.

What happens when legal needs to update the compliance language that appears on 47 pages? You grep for the old string and replace it. Except the string has slight variations. Except someone reworded it slightly on the enterprise page. Except now you need to verify each change because regex can’t understand intent. Now you are building a CMS.

What happens when you want to know “where is this product mentioned?” You can grep for the product name. You can’t grep for “content that references this product entity” because markdown doesn’t have entities. It has strings.

Suddenly you’re parsing thousands of files on every build to check for broken links (that you can’t query). And yes, you are building a CMS.

Structured content breaks the content = page assumption on purpose. A product is a document. A landing page document references that product and both are rendered together on the website. And in an app. And the support article for that product. When the product information changes, that changes is reflected in all these places. When you need to find every mention, you query the references, not the strings.

Engineers understand this. It’s normalization. It’s the same reason you don’t store customer_name as a string in every order row. You store a customer_id and join.

Markdown files are the content equivalent of denormalized strings everywhere. It works for small datasets. It becomes a maintenance nightmare at scale.

Git is not a content collaboration tool

Git is a version control system built for code. Code has specific properties that make git work well:

- Merge conflicts are mechanical. Two people edited the same function. The resolution is structural.

- Line-based diffing makes sense. Code is organized in lines that map to logical units.

- Branching maps to features. You branch to build something, then merge when it’s done.

- Async is fine. You don’t need to see someone else’s changes until they push.

Content has different properties:

- Merge conflicts are semantic. Two people edited the same paragraph with different intentions. The “correct” merge requires understanding what both people meant.

- Line-based diffing is arbitrary. A paragraph rewrite shows as one changed line that actually changes everything. If you have block content (like Notion) this breaks apart even more.

- Branching doesn’t map to content workflows. “I’m working on the Q3 campaign” isn’t a branch. It’s 30 pieces of content across 12 pages with 4 people contributing.

- Real-time matters. When your content team is distributed, “I’m editing this doc” needs to be visible now, not after a commit and push. Even more so with AI automation and agents in the mix.

None of this is git’s fault. Git solved the problem it was built for brilliantly. Content collaboration isn’t that problem.

We know this because every team that scales content on git builds the same workarounds:

- Lock files or Slack conversations to prevent simultaneous editing

- “I’m working on X, don’t touch it” announcements

- Elaborate PR review processes that become bottlenecks

- Content freezes before launches because merge complexity is too high

Sound familiar? These are the problems CMSes were built to solve. Real-time collaboration. Conflict-free editing. Workflow states that aren’t git branches.

Lee’s core argument: AI agents can now grep the codebase, so content should live in the codebase.

This sounds reasonable until you think about what grep actually does. It’s string matching. Pattern finding. It’s great for “find all files containing X.”

It’s not great for:

- “All blog posts mentioning feature Y published after September”

- “Products with price > $100 that are in stock”

- “Content tagged ‘enterprise’ that hasn’t been translated to German yet”

- “The three most recent case studies in the finance category”

Here’s what that last one looks like in GROQ:

*[

_type == "caseStudy"

&& "finance" in categories[]->slug.current

]|order(publishedAt desc)[0...3]{

title,

slug,

"customer": customer->name

}

Try writing that as a grep command against markdown files. You can’t. You’d need to parse frontmatter, understand your date format, resolve the category references, handle the sorting, limit the results. At which point you’ve built a query engine.

Structured content with a real query language is what agents actually need to reason about content. Markdown files are less queryable than a proper content API, not more.

The irony here is thick. Lee’s argument for moving to code is that agents can work with code. But agents are better at working with structured data and APIs than they are at parsing arbitrary file formats and grepping for strings. That’s not a limitation of current AI. That’s just how information retrieval works.

Here’s what we think Lee got backwards: the solution to “my agent can’t access my CMS” isn’t “delete the CMS.” It’s “give your agent access to the CMS.”

It was also bad timing. Our MCP server wasn’t good enough when Lee tried it.

But we fixed it. Our new MCP server is out now.

Your coding agent can now create new content projects, query your content, create documents, update schemas, and manage releases. All through the same interface you’re already using to build everything else. You never have to see any CMS UI unless you want to.

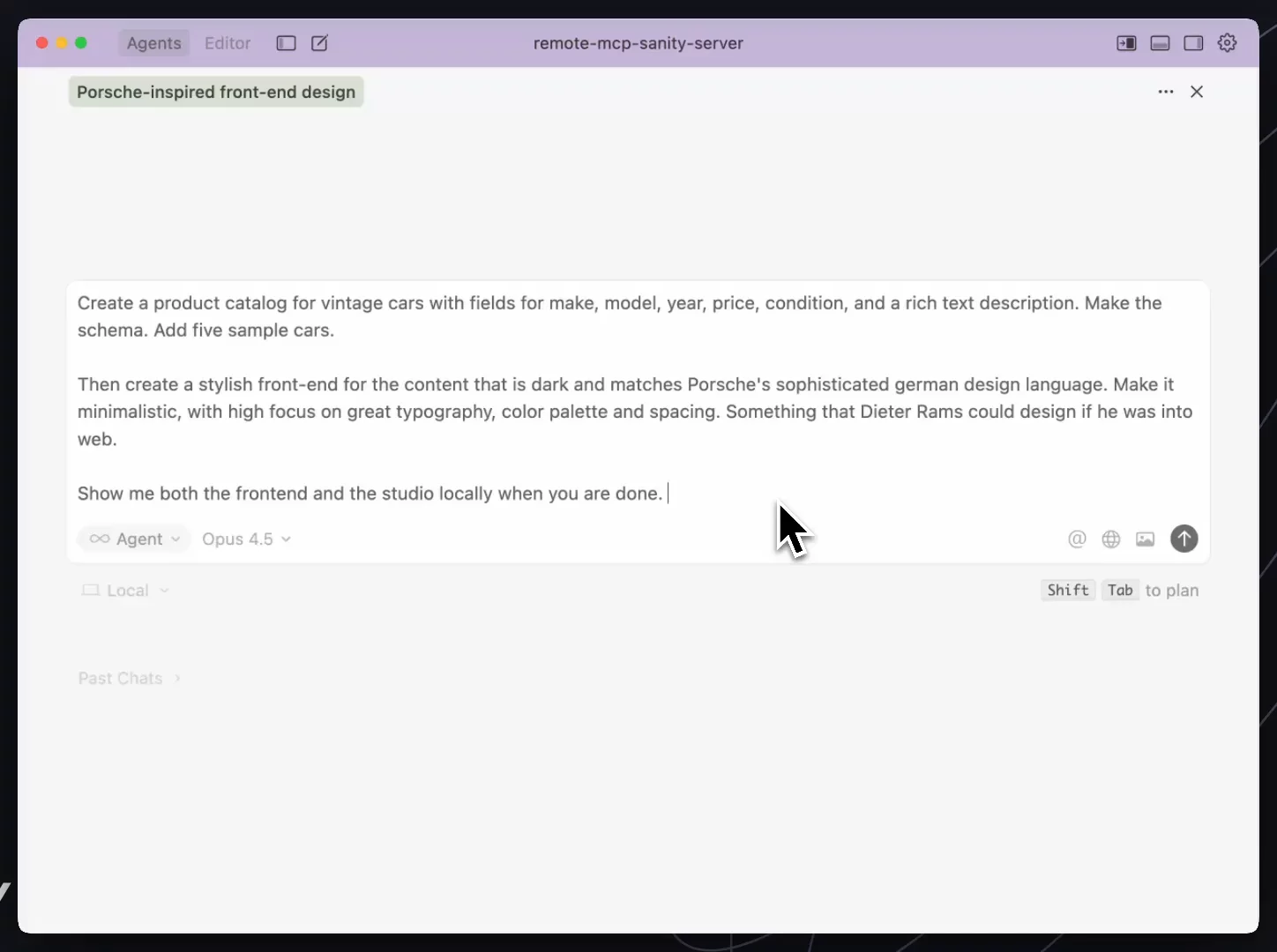

Create a product catalog for vintage cars with fields for make, model, year, price, condition, and a rich text description. Add five sample cars.

Schema, queryable content. From prompts. In about 10 minutes from start to deployed. You can ask it to generate images of those cars too.

You can also use it for content inquires like this:

Find all products missing SEO descriptionsThe agent queries your actual schema and returns actionable results. Not string matches. Actual documents with their field states.

Add an SEO metadata object to all page types with fields for title, description, and social image

The agent checks your existing schema, generates compatible additions, and can deploy them. No tab-switching to documentation. No copy-pasting boilerplate.

This is what “agents working with content” actually looks like. Not grep. A query language. Not editing markdown. Operating on structured data through proper APIs. Not string matching. Semantic understanding of your content model.

Here’s something we should acknowledge: LLMs are good at markdown. They were trained on massive amounts of it. The format is token-efficient compared to JSON and XML. When you ask an agent to write or edit prose, markdown is a reasonable output format.

This is real. It’s part of why Lee’s migration worked.

But there is a difference between “good format for LLM I/O” and “good format for content infrastructure.”

LLMs are also good at SQL (they even now GROQ fairly well when you remind them). That doesn’t mean you should store your database as .sql files in git and have agents grep them. The query language and the storage layer are different concerns.

I wrote about this three years ago in Smashing Magazine, before LLMs changed everything. The arguments still hold: you can’t query markdown, structured content is more tinker-able, and hosting content in a database doesn’t mean you own it less.

What’s changed is that we now have agents that can work with both formats. The question is which architecture sets them up to do more.

Let’s be fair about scope. Cursor’s setup works for cursor.com right now because:

- Their entire team writes code. “Designers are developers” at Cursor.

- Content has one destination: the website.

- They ship infrequently enough that git workflows are fine.

- They don’t need approval chains, compliance audits, or role-based permissions beyond what GitHub provides.

- Localization is “AI at build time.”

If your company looks like this, maybe markdown in git is fine. Genuinely.

But most companies don’t look like this.

This is what we are seeing every day:

- Content needs to flow to apps, email systems, AI agents, personalization engines. Not just one website.

- You need structured data, not just prose. Product specs. Pricing tables. Configuration. Things that need to be queryable and validated.

- You have governance requirements. “Who changed this and when” needs actual audit trails, not git blame.

- You need real-time collaboration. Multiple people and agents working on the same content simultaneously. Git merge conflicts on prose are miserable for humans and wasteful for agents.

- Content operations need to scale independently of engineering. Not because your team can’t learn git, but because content velocity shouldn’t be bottlenecked by PR review cycles.

Cursor is ~50 developers shipping one product website. That context matters.

The debate shouldn’t be “CMS vs. no CMS.”

There are definitely parts of the traditional CMS we should nuke into the sun with fire:

- WYSIWYG editors that produce garbage HTML soup

- Page builders that store content as layout blobs (you can’t query “all hero sections” if hero sections are just JSON fragments in a page blob)

- Webhook hell for basic content updates

- “Content modeling” that’s really just “pick from these 15 field types and good luck”

- Revision history that tells you something changed but not what or why

We can leave these things behind without resorting to git and markdown.

Rather, the question should be: is your content infrastructure built for AI to be both author and consumer?

That means:

- Structured, not flat files. AI that can reason about typed fields and relationships, not arbitrary strings.

- Queryable, not grep-able. Real query languages that understand your schema, not regex pattern matching.

- Real-time, not batch. Content changes shouldn’t require a deployment to be visible.

- Presentation-agnostic. No hex colors in your content model. No assumptions about where content renders. Separation of concerns.

Lee’s frustration was valid: “I don’t want to click through UIs just to update content.”

The answer is content infrastructure that works the way modern development does. Agents that understand your schema. Queries that express intent. APIs that don’t require you to build a query engine out of grep and find.

Lee’s post went viral because it resonated. Developers have real frustrations with content management tools that were built for a different era.

We know. We literally built Sanity because we were angry at the CMS industry (a.k.a “spite-driven development”)

The answer isn’t to retreat to 2002 and plain text files for agents to parse. It’s to build what actually solves the problem: content infrastructure that AI can read, write, and reason about.

You shouldn’t build a CMS from scratch with grep and markdown files. You probably shouldn’t have to click through forms to update content either. Both of these can be true.

The tools exist to have it both ways. Structured content that agents can actually query. Editorial interfaces that don’t require git. Real-time collaboration that doesn’t involve merge conflicts on prose.

That’s what we’re building. Lee’s post is a good reminder of what happens when we don’t get it right.

<a href