Birth of Benzene (Sort of)

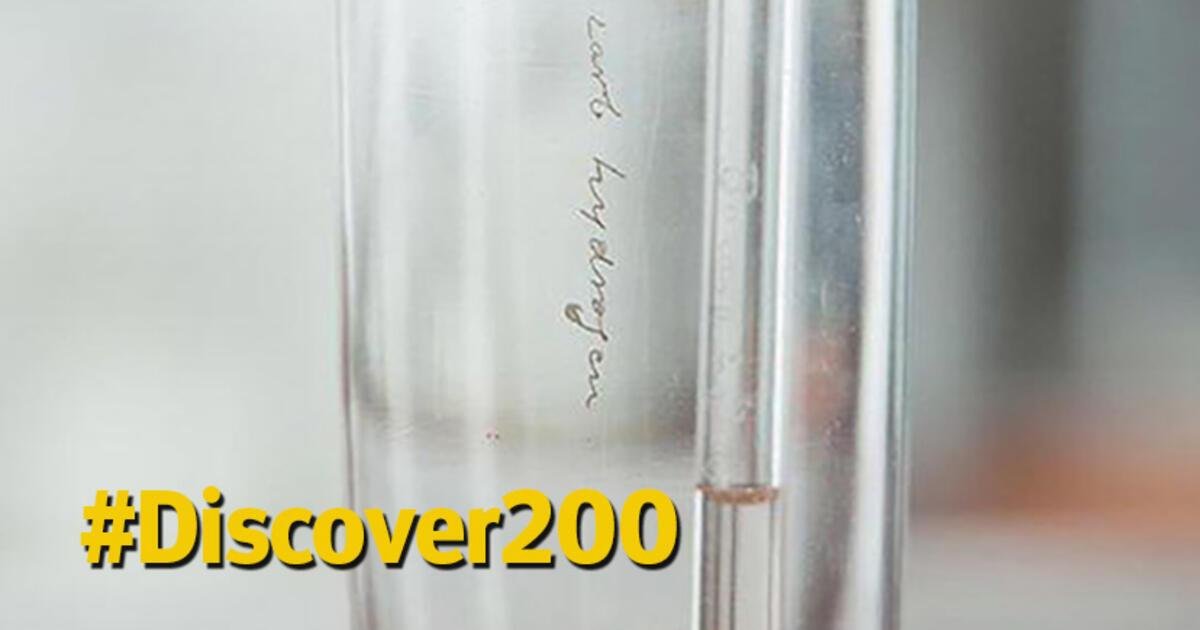

If you look carefully at the vial, you can see that Faraday has engraved the name of this substance on the glass: “Bicarburete of hydrogen,” No Benzene. You can also see this name on the margins of Faraday’s diary. Faraday’s understanding of chemical formulas was different from those we use today. After doing some calculations, he presented the substance as its proportional weight: 2 parts carbon for every 1 part hydrogen.

This name did not stick. As new routes for obtaining benzene were discovered and other chemists attempted to fit benzene into the existing understanding of chemical substances, after some permutations, the name benzene stuck. Fortunately, Faraday approved!

Chemists of the 19th century were also now discovering a whole new family of chemicals that were related to benzene. These became known as “aromatic compounds” because of their shared sweet-spicy odor. While today aromaticity has nothing to do with smell (rather it is defined as a cyclic compound), for chemists of the past their nose was an important tool for identifying compounds such as benzene.

These aromatic compounds have had a wide-ranging impact on modern life. The first major invention occurred in 1856, when an 18-year-old chemistry student named William Henry Perkin was attempting to synthesize synthetic quinine, a valuable anti-malaria drug. Perkin accidentally created something completely different. Working with aniline, an aromatic coal tar derivative containing benzene, he produced a dark precipitate, which when dissolved in alcohol reveals a beautiful purple color. This mauvein was the first synthetic dye.

Mauvemania caused an uproar throughout Victorian society. This new synthetic dye was bright and insensitive to fading, unlike natural dyes. Suddenly aromatic chemistry became fashionable, commercial, and apparently transformative. And importantly, the science surrounding benzene became incredibly profitable, and other uses for compounds like benzene began to develop.

At Rhee, Perkin’s former teacher, the famous chemist August Wilhelm Hofmann, gave a sermon on Friday evening, April 11, 1862, titled “On Mauve and Magenta.” He brought Faraday’s original benzene vial into the lecture theater and touted Faraday’s “pure research” as the gold standard of science. This was not a particularly veiled attack on Perkin, who had now made significant money from his mauvein synthesis. ri’s magazine, ProceedingContains samples of cloth dyed in various new colours. You can see how their vitality continues even today!