Important

This article was originally written in December 2021, but I’ve updated it to reflect my new configuration.

I have been an avid user of XFCE for a very long time. I’m fond of its lightweight nature and I feel productive in it. But when I first discovered tiling window managers, I was amazed. I want to use it forever.

My first experience with it was a few years ago, before I understood how Linux window managers worked. I still couldn’t wrap my head around the fact that you can install more than one window manager and choose the one you want during login. I guess I’ve grown since then. I vaguely remember trying to install i3wm, the most popular tiling window manager at the time. I guess I was surprised by the black screen and even more so by the mouse pointer, which was just said X,

About a year ago, I came across DistroTube’s YouTube channel, where he talks about xmonad, a tiling window manager written in Haskell. Although I have wanted to learn Haskell for a very long time, my career path has not given me the opportunity to learn it until now.

Since then I’ve changed jobs and moved completely to Linux everywhere. I never want to use a non-Linux machine again. I’m sure there’s an entire blog article somewhere inside me about how much of a Linux person I’ve become over the past year.

Last week, I came across DT’s video on QTile, a tiling window manager written entirely in Python. Now He It was really tempting. I am proficient enough in Python to be able to manage complex configurations on my own. And after a cursory glance through the documentation, I spent a day modularizing the default qtile configuration because the default configuration gives me goosebumps, and not in a good way.

In this article, I’ll describe what I did, and how I did it.

installing qutil#

I decided to separate the entire configuration so that it doesn’t reside in my dotfiles repository. I wanted to create a Python library for myself so that it would contain a bunch of utilities for my own consumption.

Additionally, I disagree with the default way of installing QTile. As a principle, I Never sudo pip install AnythingInstead, I asked my friend Karthikeyan Singaravel, who is a Python core developer, and he recommended using the Deadsnake PPA for Ubuntu to install whatever version of Python I chose, I tried to compile python 3,10 myself, installed /opt/qtile/ using the configure --prefix /opt/qtile/ During the configuration phase of the source code. However, I admit that using deadsnakes This is a much better idea because I can create a virtual environment based on python3.10 In /opt/qtile/ instead. I had to change the owner of the folder to my user account. Note that I can Store the virtual environment in your home folder and just use that, but I wanted to separate it Outside Of my home folder.

installation approach

The key principle here is isolation – keeping Qty’s dependencies separate from the system Python and user Python environments. This prevents conflicts and makes updates easier.

So, I installed python3.10-full And python3.10-dev (Development header files are required to build some dependencies qtile), and I created a virtual environment using venv in module /opt/qtileThen, I changed the owner of the folder to my regular user account,

Then, it’s time to install QTile.

Since I use fish shells, I had to source activate /opt/qtile/bin/activate.fish To activate the virtual environment. and then i continued to install qtileI didn’t choose a version right away, I decided to go with the latest version,

Qtile doesn’t setup any entries for you xsessionsSo you need to do it yourself.

i made /usr/share/xsessions/qtile.desktop And fill it with the following:

|

|

Notice how I used it absolute Path to Qty.

Next, I logged out of my previous window manager and switched to the new entry for Qtile.

Upon loading qtile for the first time, I was quite surprised by the default configuration. it was not like that Empty As were i3wm and xmonad. It had a panel, there was a helpful text field on the panel about how to start the launcher, and it was very easy to use. I was already liking it.

But I wanted to configure it so I could play around with the design.

The first thing that bothered me was the lack of wallpaper. I had used Nitrogen before, so I installed it and started it up, setting the wallpaper. I restarted qtile and then… nothing.

That was me being a fool and forgetting her Explicit is better than implicitLike all tiling window managers, Qtile didn’t do the trick for us, You have to make sure that Wallpaper Manager Burden When Qtile is loaded. it is right here .xsessionrc The file arrives.

Since nitrogen can restore wallpaper easily, all I had to do was:

it went in ~/.xsessionrc file.

configuring qtile#

Qtile’s config file is located here ~/.config/qtile/config.pyInitially, Qtile will be Reading this file. Since this file is just Python code, it also means that every line of this file is executed.

When you look at the default configuration, you will see:

- It is approximately 130 lines long. not too big.

- It’s just a bunch of variable declarations.

This meant that to configure Qtile you just had to make sure you set the values of some global Variable in config file. And Qtile will take care of the rest.

This was useful. I just needed to set a few variables.

The default configuration creates all of these variables the same way it sets them, which is something I don’t recommend. Python’s error handling will not tell the exact place where the error is occurring, and while Python 3.11 attempts to improve this, it is generally not a good practice to have a long variable declaration step in your code.

For example, where the configuration does this:

|

|

if you want reuse It is better to create these items separately and then use them in a panel. The same applies for reusing panels.

My current configuration#

After months of tweaking and refinement, my current QTile setup looks like this. The key principles I adopt are:

- modularity: break down complex structures into functions

- favorable behavior: Detect hardware and adjust accordingly

- practical shortcuts:Keybindings that are suitable for daily use

- visual consistency:A consistent color scheme and layout

Color Scheme and Properties#

|

|

I use a consistent color palette and have custom icons for different system components. The straw hat is a personal touch – a nod to One Piece!

Smart mouse movement between monitors#

One of my favorite custom functions handles multi-monitor setups elegantly:

|

|

When I press it it automatically moves the mouse cursor to the center of the next monitor Super + .Which makes multi-monitor workflow more seamless.

key bindings#

My keybindings follow a logical pattern:

- super + hjkl:vim-style window navigation

- super + shift + hjkl: move windows around

- Super + Control + HJKL:resize windows

- super + r:Launch Rofi Application Launcher

- Super + Shift + P:Screenshot Utility

- Super + Shift + L: lock screen

- Super + Shift + E:Power Menu

|

|

Hardware-aware widgets#

One of the most powerful aspects of a Python-based window manager is the ability to create intelligent, hardware-aware components:

|

|

These functions automatically detect hardware capabilities and adjust the interface accordingly. The battery widget is only visible on laptops, and the IP address widget shows the current network status.

AMD GPU integration#

Since I run AMD hardware I’ve integrated it amdgpu_top For real-time GPU monitoring:

|

|

It provides real-time VRAM usage information directly in the status bar.

Dynamic Screen Configuration#

The screen configuration automatically adapts to the number of connected monitors:

|

|

The main screen gets additional widgets like the system tray and network information, while the secondary screen gets a simplified layout.

Startup Hook#

Qtile provides hooks to run scripts at startup:

|

|

This lets me separate one-time setup (like setting the wallpaper) from things that need to happen on every reload.

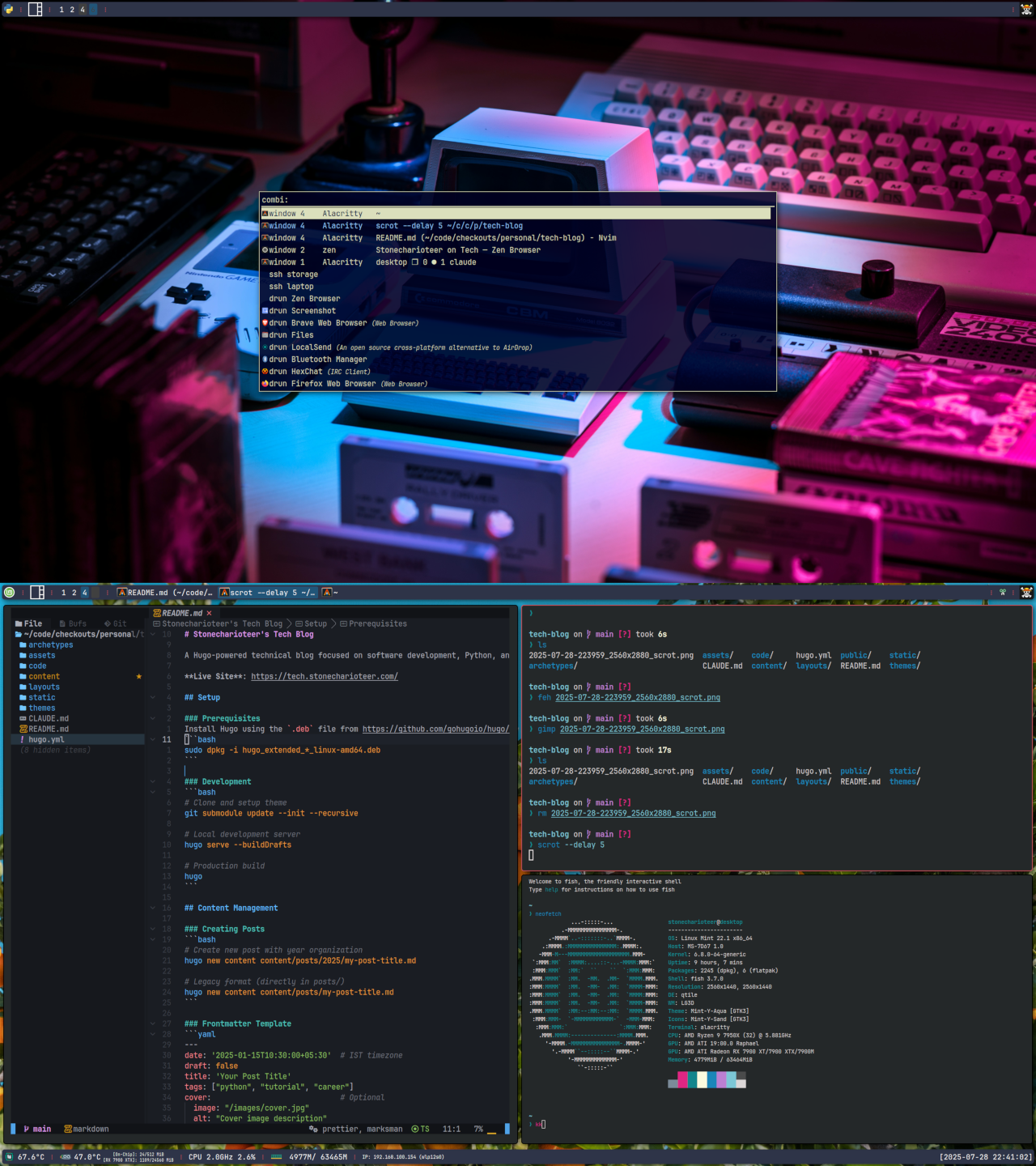

Current setup in action#

My current setup includes:

- top bar: Shows the Linux Mint logo, current layout, groups (workspaces), task list, and system tray.

- lower bar: CPU/GPU temperature, VRAM usage, system resources, battery (if present), IP address and clock

- custom separator:Visual separator using the “⋮” character in my accent color

- jetbrains mono nerd font: for consistent icon rendering across all widgets

font selection

It is important to use the Nerd font for proper icon rendering in Qtile widgets. JetBrains Mono provides excellent readability while supporting all essential symbols.

Lesson learned#

After using Qtile daily for months, here are the key findings:

Python configuration is powerful#

Keeping your window manager configuration in Python means you can:

- Write complex logic for hardware detection

- Create reusable functions and modules

- Integrate seamlessly with system tools

- Debug configuration issues using Python tools

Start simple, iterate#

Don’t try to recreate someone else’s rice right away. Start with the defaults and gradually adapt:

- Basic keybindings first

- Add required widgets

- Customize colors and fonts

- Add advanced features like custom functions

Hardware Awareness Issues#

Modern systems differ considerably. Your configuration should be compatible with:

- number of monitors

- presence of battery

- available sensors

- network interface

Performance Considerations#

Since widgets can run arbitrary Python code, be careful:

- Update interval for poll widget

- Error handling in custom functions

- Resource usage of external commands

future plans#

This configuration is constantly evolving. Some planned improvements:

-

custom widget,

- One Piece Chapter Release Notifications

- Gmail Filtering Widget

- tmux session manager

- Kubernetes Reference Indicator

-

Better multi-monitor support,

- Per-monitor wallpaper management

- Workspace bindings to specific monitors

- Dynamic layout switching based on monitor configuration

-

integration improvement,

- nordvpn status widget

- NAS storage monitoring

- Better notification management

Preview#

Here’s what my configuration looks like today.

conclusion#

QTile has changed my Linux desktop experience. The ability to configure everything in Python, combined with the logical tiling approach, has made me significantly more productive. The learning curve is softer than pure configuration-file-based window managers, and the extensibility is unmatched.

If you’re comfortable with Python and want a window manager that adapts to your needs, Qtile is an excellent choice. The community is helpful, the documentation is extensive, and the possibilities are endless.

The configuration I shared represents months of daily use and refinement. It’s not just about aesthetics (although it looks good!) – it’s about creating a workspace that suits your hardware, workflow, and preferences.