The early poetry of the writer JM Coetzee is almost incomprehensible. This is because it was written in computer code.

Coetzee’s global reputation rests on his literary output, for which he received the Nobel Prize in 2003. Before embarking on a career as a scholar and writer, the South African-born author was a computer programmer in the early years of the industry’s development (1962–1965). I believe that this experience, however short, was crucial to the development of Coetzee’s writerly project. While visiting the Ransom Center on a research fellowship, I examined Coetzee’s documents, which yield fascinating clues about his neglected “other careers.”

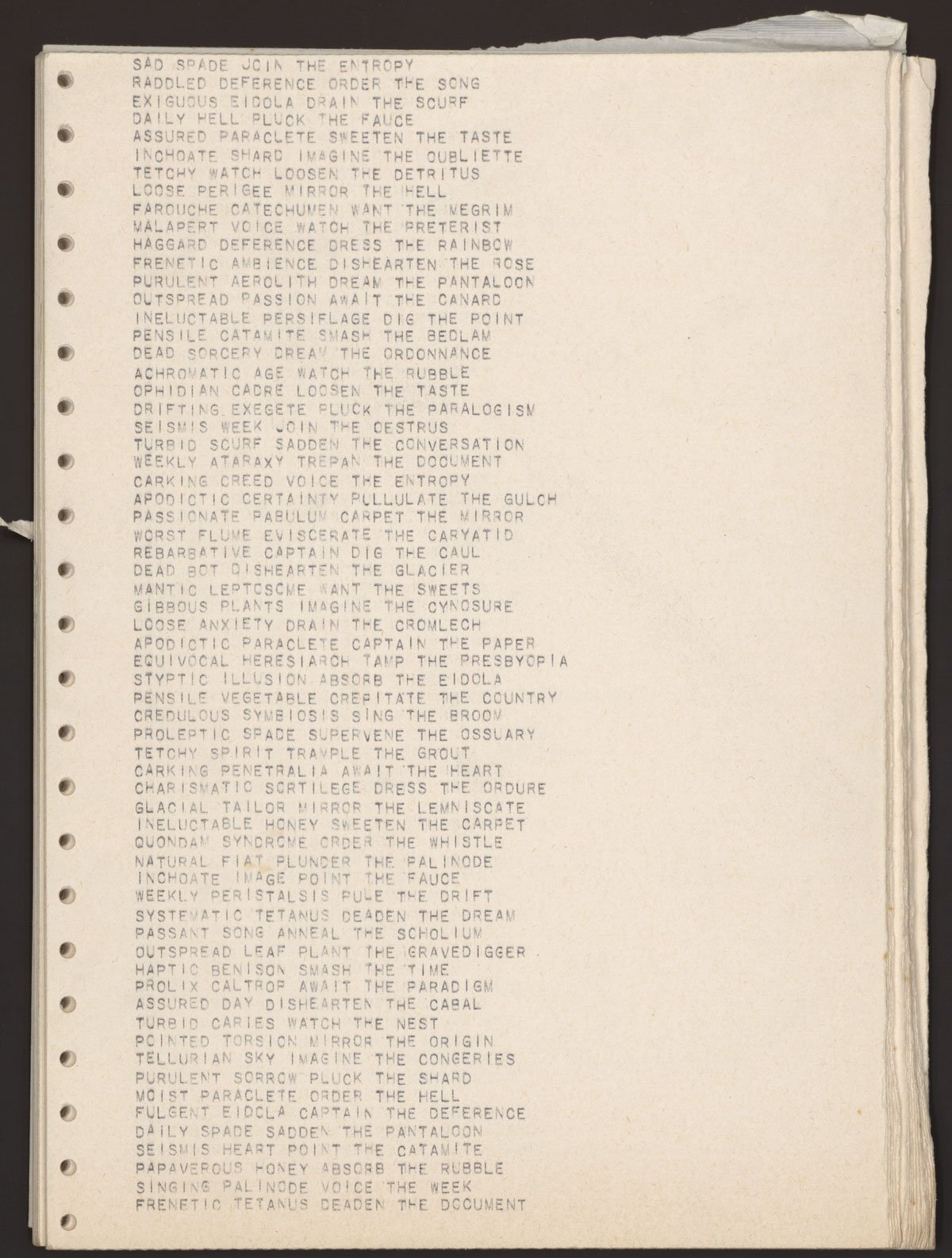

In the mid-1960s Coetzee was working on one of the most advanced programming projects in Britain. During the day he helped design the Atlas 2 supercomputer for the United Kingdom’s Atomic Energy Research Establishment at Aldermaston. At night he used this extremely powerful Cold War machine to write simple “computer poetry”, that is, he wrote programs for a computer that used algorithms to select words from a set vocabulary and create repetitive lines. Coetzee never published these results, but edited and incorporated phrases from them into poetry which he published.

While Coetzee was never in danger of starting World War III, these important experiments have flown under the radar of both Coetzee scholars and historians of computing. Coetzee’s readers may be familiar with these experiences from his descriptions in his second “imaginary autobiography”. Youth (2002), but Coetzee’s role in the Atlas 2 project and his continuing interest in computing throughout his academic and literary career have been largely ignored.

While at the Ransom Center I was able to examine print-outs testifying to Coetzee’s poetic generation on Atlas 2. I’m asking to check because reading them resulted in a steep learning process on my part: some binary and hexadecimal numbers were written in strings. This individual “machine code” is designed to give instructions to the computer, but it is difficult for programmers to read and almost incomprehensible to me. Other documents were written in FORTRAN, the first high-level programming language, developed in the late 1950s as a language that was easy for human users to write and read, but could then be easily “translated” into machine code via a compiler. Still others were written in Fortran “pseudocode”, a specialized form of notation that a programmer like Coetzee could develop (a kind of personal shorthand) that looks like Fortran but is not executable.

Excitingly, I was also able to examine Coetzee’s natively-digital materials obtained from 5.25″ and 3.5″ floppy diskettes. This was invaluable, and helped me establish a timeline of what types of computing hardware and software Coetzee was using throughout his writing career. I am extremely grateful to Abby Adams, the Center’s digital archivist, for devoting so much of her time before and after my arrival to making this collection available. Without their help, my research would have been limited to consulting print-outs of such digital materials – useful, but less than ideal! Thanks to them, I was able to establish several file types of Coetzee’s records, which would help me determine the software on which he wrote most of his novels.

Although it is still early days for this research project, Coetzee’s access to electronic files, programming records and outputs has given rise to a number of fascinating challenges and research questions: How do you read code? What is the “text” of a program – machine code, high-level programming, or the output it produces? How do you protect an electronic file and how should the scholar access it? As more and more writers create born-digital archives, these questions will become more urgent for archivists and literary scholars. Looking at Coetzee’s other career will, I hope, help to clarify some of these issues.

Rebecca Roach is a postdoctoral researcher at King’s College London. His current book project, of which his work on Coetzee is part, is titled “Machine Talk” and explores communication and collaboration in digital literature. His fellowship at the Ransom Center was supported by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Research Fellowship Endowment.