Today, a young man down on his luck in a new city is more likely to end up in jail or on the streets than standing on his own feet. Fifty years ago they had another option. A place to wash up, get a hot meal, meet other young people – even a place to start again. He just had to put his pride on hold and get himself to—well, you can pronounce it: the YMCA.

The Village People’s 1978 disco hit celebrated one of the lesser-remembered services provided by the YMCA. YMCA construction begins in the 1860s occupancy of a room (SRO) units “to provide safe and affordable housing to youth coming from rural areas to the city.” At its peak in 1940, the YMCA had more than 100,000 rooms – “more than any hotel chain at that time.” The Y was not the only provider of such accommodation; In fact, there was a vibrant market for hotel accommodation that existed well into the twentieth century.

Variously and derogatorily known by many names – rooming houses, lodging houses, flophouses – SROs provided affordable, market-rate housing to people at the bottom of the socioeconomic ladder. SROs were the cheapest form of residential hotels, specializing in single rooms furnished for individuals, usually with shared kitchens and bathrooms. A typical SRO rent in 1924 was $230 per month.in today’s dollars,

By the late 1990s, nearly 2 million people lived in residential hotels—more than “all the public housing in America”—according to Paul Groth, author stay downtown, Today, not so much. SROs like those offered by the YMCA were safety nets that kept many people off the streets – and their disappearance from the housing supply explains modern-day homelessness. What we destroyed was not just one type of housing, but an entire urban ecosystem: one that provided flexibility, freedom, and affordability on a large scale.

Like much of our urban history, this destruction was deliberate.

From the mid-1800s to the early 1900s, hotel living was a common way of life for people of all socio-economic backgrounds. As hotel operator Simeon Ford eloquently stated in 1903, “We have good hotels for good people, good hotels for good people, plain hotels for plain people, and some worthless hotels for idiots.” SROs, “bomb hotels”, were the backbone of affordable housing, serving “a great army” of low-wage but skilled workers. Grouped into vibrant downtown districts with restaurants and services that functioned as extensions of the home, SROs provided freedom from the constraints of familial supervision and Victorian customs. Rooming house districts allow youth to mix freely and even allow same-sex couples to live together discreetly – indicative of a more secular, modern urban culture. Downtown hotel life, Groth notes, “had the promise of being not just urban but urban.”

And herein lay the problem: the urbanity of SROs conflicted directly with the morals of the Progressive Era.

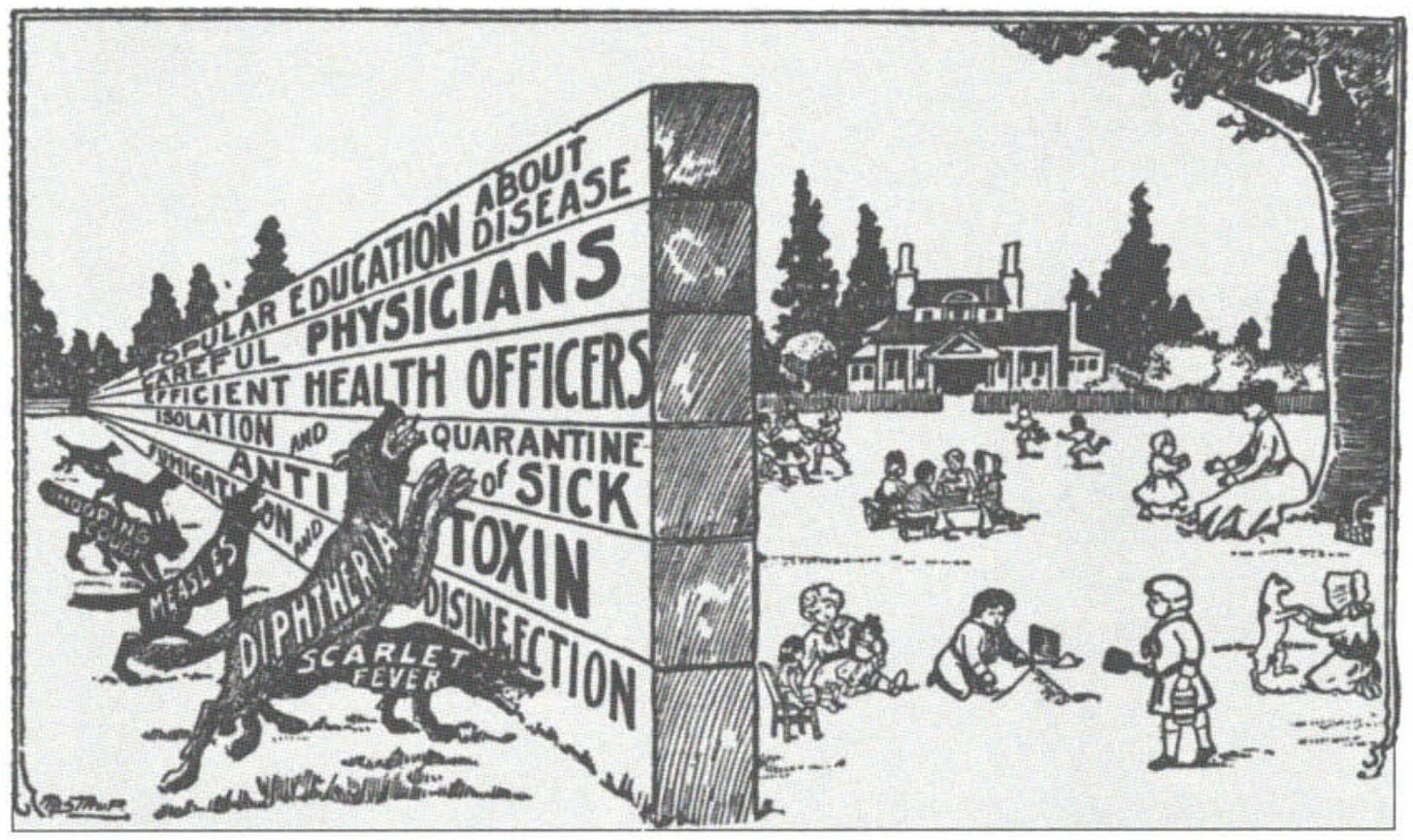

Reformers drew on a long tradition anti-urban biasSeeing the emerging twentieth-century city as a problem, with cheap hotels at its core. He described the hotel residents as “friendless, isolated, needy, and disabled” and described SROs as “centers of social and cultural evil.” some of the cheapest hotels Were Unsafe and exploitative, but reformers cared less about improving conditions than symbolizing the hotels. They blamed rooming houses for loneliness, sexual immorality, civic apathy – even suicide. To him, the presence of “social misfits” proved that hotels lead to moral disorder. In fact, people lived in SROs because they were cheaper and provided more independence – especially for career-oriented young women. Firm in their belief in “the one best way to live”, reformers revered the single-family home as a “bastion of good citizenship” and succeeded in destigmatizing hotel life.

By the turn of the century, he focused his attention on changing the law.

Beginning in the late 19th century, reformers used building and health codes to eradicate “abnormal social life”. San Francisco’s early building ordinances targeted Chinese dwelling houses, while later codes outlawed cheap wooden hotels altogether. By the early 1900s, cities and states were classifying boarding houses as a public nuisance. Other laws increased building standards and mandated plumbing fixtures, which increased costs and slowed the pace of new construction. After this urban reformers adopted exclusionary zoning To separate unwanted people and harmful uses from residential areas. SROs were considered inappropriate in residential areas, and many codes banned mixed-use districts that maintained them. In cities such as San Francisco, zoning was used to create a “cordon” around the pre-war city to “protect views of the old city from contaminating the new one.”

Residential hotels, like apartments, fell into the same category of “mere parasitic” use. Euclid vs Ambler– a 1926 case that upheld zoning – were considered potential health hazards. Redlining and federal lending criteria starved the capital’s urban hotels, while planners omitted them from surveys and censuses – as if their residents did not exist. From urban renewal In that era, the very existence of the Old City was seen as a disgrace, and it too had to be destroyed.

In effect, SROs became “intentional casualties” of the new city.

Economic and policy changes hastened their decline. Industrial jobs moved to peripheral locations accessible only by car, urban highway expansion targeted single-home neighborhoods, and cities encouraged office development on increasingly valuable downtown land. The “moral decline” of hotel districts had rapidly become an economic crisis, requiring renovation. And because SROs are not counted as “permanent housing” in official statistics, evacuation programs cannot claim to displace anyone. San Francisco’s urban renewal experience was typical: redevelopment in and around the Yerba Buena/Moscone Center area ultimately eliminated an estimated 40,000 hotel rooms. The public housing that replaced hotel districts – if it was built at all – often failed to accommodate single adults. For bureaucrats, the bulldozer was beneficial, “eliminating dead tissue” and “redressing the mistakes of the past.” For the people living there, it also wiped out their last foothold in the housing market.

By the mid-twentieth century, “millions” of SRO hotel rooms disappeared due to closures, conversions, and demolitions in major cities, and what little hotel market remained was rapidly shrinking. With almost no new SROs being built since the 1930s, the remaining stock was disappearing by the thousands by the 1970s. When New York City banned new hotel construction in 1955, there were 200,000 SROs; By 2014 only 30,000 were left. As tenants changed and land values rose, owners who once fought to save their tenement houses now wanted out; It was the authorities who suddenly wanted to protect him. The tenant movement and new government programs emerged in the 1970s and 80s, but Reagan-era cuts eliminated funding, and many remaining hotels were transformed into the “street hotels” that opponents had long envisioned: unsanitary, unsafe, and unfit for all but the city’s most desperate residents.

At the same time, demand for SRO housing was growing rapidly. In the 1970s, states emptied mental hospitals without funding options, pushing thousands of people with serious needs into cheap city hotels that had no facilities to support them. What was left of the SRO system became America’s emergency shelter network – the last leg of shelter for people who had been abandoned by the state.

Thousands of people were barely surviving, and there was a full-scale crisis of homelessness in American cities for the first time since the Great Depression.

Groth argues that the SRO crisis was not an accident, but the result of government policy at all levels that picked winners and losers in the housing market. The people we now call “chronically homeless” were once simply low-income tenants, placed in affordable rooms by the private market rather than public programs. Once that market ended, the outcome was predictable: homeless The wave of the late 1970s and 1980s resulted directly from the destruction of SROs. Today’s crisis – nearly 800,000 people homeless by 2024 – is the long tail of that harm, exacerbated by decades of underbuilding and rising rents in expensive cities. As a lawyer said“The people you see sleeping under bridges used to be valuable members of the housing market. They’re not anymore.”

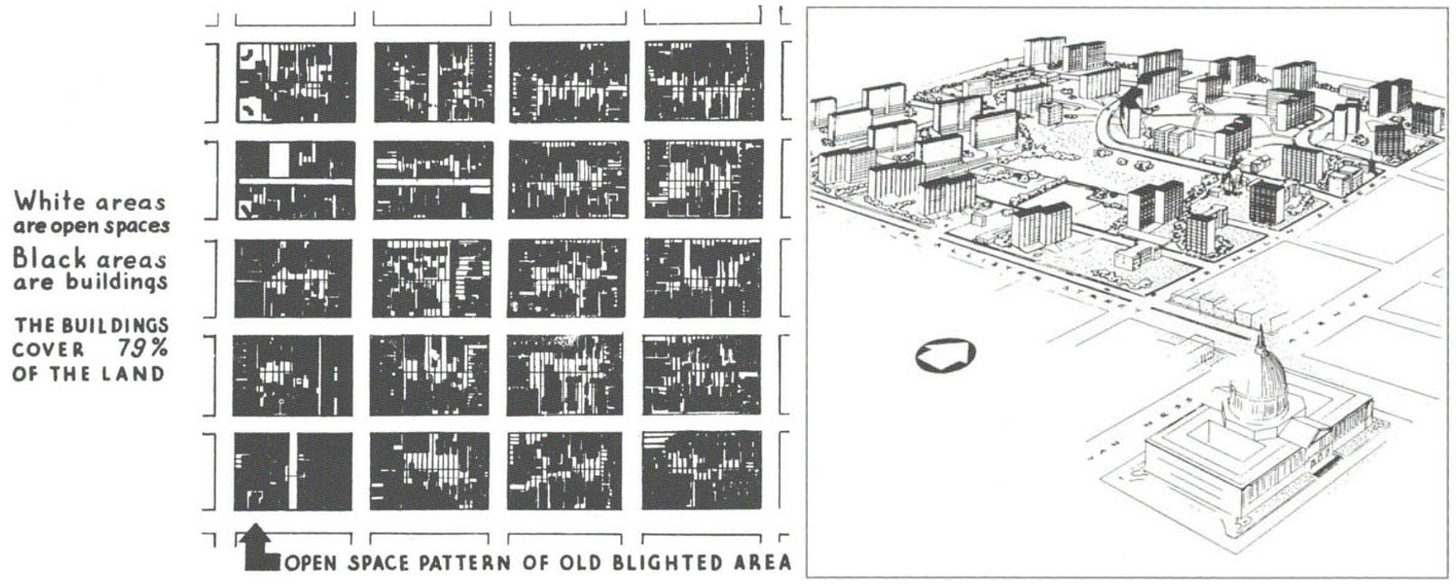

As Alex Horowitz of the Pew Charitable Trusts writesIf SROs “had grown at the same rate as the rest of the US housing stock since 1960, there would be approximately 2.5 million such units in the country” – more than three times the number of homeless individuals. Although we can’t rebuild the old SRO market that was destroyed, cities now face a new opportunity: a vast surplus of obsolete office space that can be converted into cheap rooms.

Horowitz argues that cities should re-legalize shared housing—”co-living” in today’s parlance. Office vacancies are rising and at the same time affordable housing is disappearing. Horowitz & Architecture Firm gensler It demonstrated what cities could actually build. Their analysis shows that a vacant office tower can be converted into extremely affordable rooms for half the per unit cost of a new studio apartment. A typical 120-220 sq ft unit with shared kitchen and bathroom can be rented to people earning 30-50% of the area average income. Urban development has become so expensive that such conversions are only possible if subsidized, but Horowitz argues that conversion offers a better way to take advantage of scarce public dollars: For example, a $10 million budget could build 125 co-living rooms instead of 35 studios, providing a way to scale up intensive affordable housing more quickly.

It’s a good idea—but in many cities, it’s illegal.

While many cities have made efforts to eliminate SRO restrictions, in many American metropolises, restrictions abound – from zoning that bans shared housing or residential use in office districts, to minimum-unit-size regulations that outlaw SRO-scale rooms. building code with strict Exit and corridor rules And ventilation requirements make conversion technically infeasible, while parking mandates add unnecessary costs. Meanwhile, “unrelated occupancy” limits prohibit the types of homes that SROs can serve.

None of these barriers are structural; Every individual is a policy choice.

We talk endlessly about the “missing middle.” But the real catastrophe was the “expunged bottom” – the deliberate destruction of the cheapest rung of the housing ladder. Re-legalizing SROs would not immediately restore the affordable housing market that provides mass housing, but it would at least make it possible for cities to create a much cheaper form of housing that could benefit some of the 11 million extremely low-income renter families and 800,000 homeless people in the US. No city will meaningfully address the need for affordable housing until it restores this missing footing — and acknowledges that not everyone needs a perfect apartment to live a full life. Sure, an SRO is better than sidewalks.

Incidentally, while the YMCA is no longer generally in the SRO business, it Austin branch is redeveloping itself as a mixed-use center with 90 highly subsidized affordable units for families. It’s a worthy project — but it highlights the gap: More than 80% of Austin’s homeless residents are single adults, the same group that once lived in the Y. We used to have a place where they could go—but so what He,

Y is as much a question as it is an answer.