The Linear Representation Hypothesis (LRH) has been around for quite some time, ever since people noticed that the word embeddings produced by Word2Vec satisfy some interesting properties. If we consider $E(x)$ to be the embedding vector of a word, you see the approximate equivalence

$E(“\text{king”}) – E(“\text{man”}) + E(“\text{woman”}) \approx E(“\text{queen”})$.

Observation of this form shows that concepts (i.e. gender in the example) are represented linearly in the geometry of the embedding space, which is a simple but non-obvious claim.

|

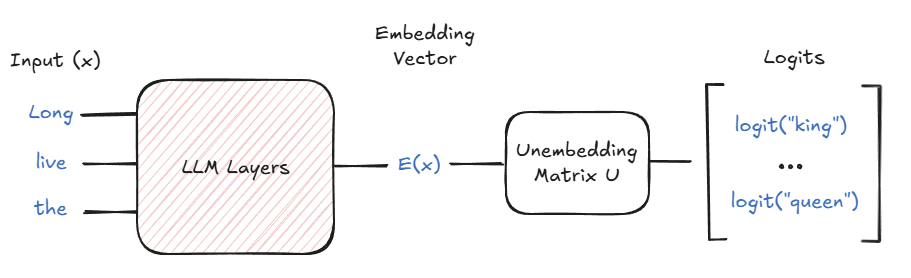

| Simplified model of LLM in terms of embedding and unembedding. |

Modern LLMs are rapidly moving forward, and LRH remains a popular way of explaining what is going on inside these models. Park et al. The paper presents a mathematical outline of the hypothesis to try and formalize the idea. It uses a simplified model of the LLM where most of the internal functioning (multilayer perceptron, attention, etc.) is treated as a black box, and the LRH is interpreted in two different representation spaces with the same dimensionality as the model:

- The “embedding space” is where the final hidden states of the network reside ($E(x)$ for the input context $x$). This term is similar to the embedding formulation and is where you will make interventions that affect the behavior of the model.

- The “unembedding space” is where the rows of the unembedding matrix reside (U(y)$ for each output token $y$). The concept direction measured by a linear probe at the hidden position (to evaluate the presence of the concept) corresponds to a vector in this space.

There are formulations corresponding to LRH in two related places. Let $C$ represent the directional concept of gender, i.e. male => female. Then any pair of input contexts that differ only in that concept must satisfy it, e.g.

$E(“\text{Hail the Queen”}) – E(“\text{Hail the King”}) = \alpha \cdot E_C$

where $\alpha \ge 0$ and $E_C$ is a constant vector in the embedding space called the embedding representation. Similarly, any pair of output tokens that differ only in that concept must satisfy it, for example

$U(“\text{queen”}) – U(“\text{king”}) = \beta \cdot U_C$

where $\beta \ge 0$ and $U_C$ is a constant vector in the unembedding space called the unembedding representation. Essentially, applying the concept has a linear impact on both locations.

The paper goes into more detail which I will skip here, but they show that these representations are isomorphic, unifying interference and linear detection ideas. They then verify empirically on Llama 2 that they can find embedding and unembedding representations for different concepts (e.g. present => past tense, noun => plural, English => French) that approximately fit their theoretical framework – great!

|

| Approximate orthogonality of concept representation in Llama 2. Source: Park et al. |

OK, so let’s assume that concepts actually have linear representation. It would then be logical that unrelated concepts have orthogonal directions. Otherwise, implementing the male => female concept may affect the appearance of the English => French concept, which makes no sense. One of the key results of Park et al. Is this orthogonality not under the standard Euclidean inner product, but under a “causal inner product” derived from the unembedding matrix. Only by looking at concept representations through that lens do we get the stereotypy we expect.

But in these models, the representation space is relatively small (at most 2K to 16K dimensions). So how do these spaces “fit” such a large number of language features that far exceed their dimensionality? It is impossible for all such features to be orthogonal, regardless of the geometry.

|

| Interference effects of non-orthogonal features. Source: Anthropological. |

This is where superposition comes into play. In low-dimensional spaces, the intuition is that, when you have $N$ vectors with $N > d$ in a $d$-dimensional space, they start to interfere significantly (the magnitude of the inner product is large). This is one of the examples where low-dimensional intuition does not extend to higher dimensions, however, as evidenced by the Johnson–Lindenstrauss lemma. One implication of the lemma is that you can choose exponentially (in the number of dimensions) many vectors that are nearly-orthogonal – that is, the inner product between any pair of vectors is bounded by a small constant. You can consider this the flip side of the curse of dimensionality.

The Anthropic paper demonstrates superposition phenomena in toy models on small, synthetic datasets. A particularly interesting observation is that superposition does not occur with no activation function (purely linear computation), but it occurs with a nonlinear one (ReLU in their case). The idea is that non-linearity allows the model to manage interference in a productive way. But this still works well only because of the natural sparsity of these features in the data – models learn to superimpose features that are unlikely to exist together.

|

| Visualization of a square antiprism, an energy-minimizing arrangement of 8 points on a 3-D unit sphere. |

In experimental setups where features in synthetic data are of equal importance and sparsity, they observe that the embedding vectors learned by the model form regular structures in the embedding space, such as tetrahedrons, pentagons, or square antiprisms. Coincidentally, these are the same types of structures I worked with in some earlier research I did on circular codes. These structures emerged from using gradient descent-like algorithms to minimize the energy of arrangements of points on the unit hypersphere (analogous to that described by the Thomson problem). It’s fun to see the overlap of so many areas!

To conclude, features as linear representations, even if not the whole story, are a valuable framework to help us interpret and intervene in LLM. It has a solid theoretical foundation that is empirically supported. Sparseness, superimposition, and the non-intuitive nature of high-dimensional spaces give us a window into how the complexity (and intelligence?) of language is captured by these models.

<a href