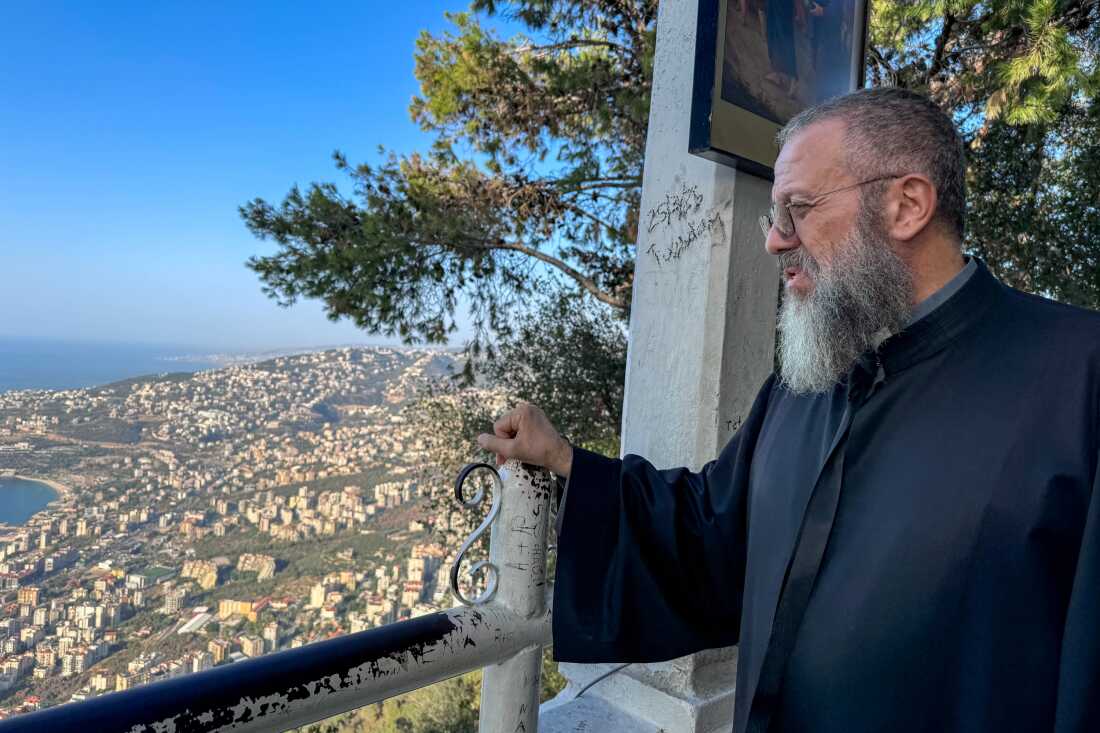

Father Fadi Al-Meir looks towards the Mediterranean Sea from Our Lady of Lebanon Sanctuary. Pope Leo will meet with clergy and other church officials there.

Zane Arraf/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Zane Arraf/NPR

Harissa, Lebanon – In the mountains near Beirut, a colossal statue of the Virgin Mary, atop a spiral pedestal, with her hands outstretched in the direction of the Mediterranean Sea, is visible beyond the railing of the Our Lady of Lebanon Sanctuary.

It is a quiet place; However, it is far from immune to the country’s economic turmoil and endless cycle of security threats.

Lebanon is a small multi-faith country with about 30 percent Christian population – the largest percentage of any country in the Middle East. Last week the country quietly celebrated its 82nd Independence Day from French rule – without any grand parade or celebration, what Lebanese typically call a ‘situation’.

The current situation follows a years-old ceasefire with Israel that Israeli forces regularly violate, including in a drone strike in Beirut last week that killed the second-in-command of the terrorist group Hezbollah. The country’s financial collapse in 2019 and a devastating port explosion a year later that killed 218 people still cast a long shadow.

A statue of the Virgin Mary overlooking the Mediterranean Sea at Our Lady of Lebanon. The sanctuary is an important pilgrimage site for Christians and Muslims, who also revere Mary as the mother of the Prophet.

Zane Arraf/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Zane Arraf/NPR

Lebanese/American event organizer Neiman Azzi has been tracking the progress of preparations for the Pope’s visit in the Maronite Catholic Patriarchate. Azzi says security is paramount in the preparations but he hopes the visit will send a message that Lebanon is not about war and killing.

Zane Arraf/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Zane Arraf/NPR

“The mission of the Church is for everyone, for all of Lebanon,” says Father Fadi El Meir, in charge of logistics for the papal visit to Our Lady of Lebanon, where Pope Leo will address clergy and other religious workers on Monday. “Poverty in our country is increasing every day and that is why the Pope will say a lot of things to encourage us to be more effective in society and especially in our Church.”

In France he ministered to struggling young Lebanese who not only moved, he says, but “escaped” an impossible situation in Lebanon, where there are few opportunities to earn a living or provide for a family.

Father Fadi, who has served in missions including South Africa and France since being ordained in 1967, says people want the church to be more “compassionate” and responsive to them, especially in Lebanon’s many Catholic-run hospitals and schools.

He speaks matter-of-factly about the time he was shot at when he was in charge of a school in the southern Lebanese city of Tyre.

“They shot at the doors when I was coming in. I don’t know why,” he says, shrugging.

They say that this was the same big Christian school where 40 years ago a pastor was murdered by terrorists who did not want it there. Southern Lebanon is predominantly Shia Muslim, as is the student population in Catholic schools, which are widely considered to provide a better education than the public school system.

Father Fadi says any tension between religious groups in Lebanon is politically motivated – not rooted in the community.

Israeli attacks during the war with Hezbollah have devastated Christian and Muslim villages along the Lebanese-Israeli border in the south.

Many Christians there are angry that Pope Leo will stay in Beirut and northern Lebanon during his visit.

Father Fadi, a member of the Lebanese organizing committee for the trip, says he told Vatican Pope Leo that they should go south.

“I said ‘The people there need their presence. It would be great for them to see people from that area, in Tyre,'” he says. “He said ‘No, no, it’s impossible’.”

He says he understood it was for security reasons.

There are statues of Jesus and the Virgin Mary in a grotto in Canna, in what is now southern Lebanon, where Jesus is believed to have performed his first miracle – turning water into wine. Christians are now a small minority in the mostly Muslim village of Kanna.

Angie Majd/Zane Arraf/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Angie Majd/Zane Arraf/NPR

‘Source of strength for us’

The Tire district in southern Lebanon includes the part of the Galilee that extends into northern Israel. It is here that Jesus is believed to have preached, including the village of Canna in what is now Lebanon. According to the Bible, at a wedding in Canna Jesus performed his first known miracle – turning water into wine.

Christians in Kanna are now a small minority among the Muslim residents. The mountain grotto where Jesus and Mary rested is open to visitors, but was deserted on a recent afternoon — lit candles were evidence of prayers but not a single visitor.

The nearby village of Alma al-Chaab, the only 100 percent Christian community left in the Tire district, has only a fraction of its population left after Israeli air strikes during the war with Hezbollah destroyed or damaged about 300 homes as well as the town’s infrastructure.

Mayor Chadi Sayah, elected five months ago, has arranged for a new ambulance with donations from city residents and a new garbage truck after the previous one was destroyed.

Like many villages, people here work and save for decades to build multi-generational homes. Some of the damaged houses were small stone houses up to 400 years old; Other new construction with swimming pool and now destroyed gardens.

Chadi Sayah, the new mayor of Alma al-Chaab, in front of a destroyed house. Before the destruction the village used to hold street festivals including Christmas celebrations. Sayah, a math teacher, says that the townspeople have pooled their money to replace the destroyed ambulance and they have a new water tank and garbage truck. But there is still no electricity or running water.

Zane Arraf/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Zane Arraf/NPR

The ruins of a house in the village of Alma al-Chaab, near the Israeli border. This number is a file for any future claims for reconstruction by the Lebanese or regional government. Lebanon is going through an economic crisis and says it has no money to rebuild – displaced residents say they have saved for years to build homes and are left with nothing.

Zane Arraf/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Zane Arraf/NPR

Almost everything grows here – oranges, olives, avocados and pomegranates. There are palm trees and pine trees that produce precious pine nuts – a source of revenue for the village. Sayah points to an area where hundreds of cedar trees were cut down during Israel’s capture of the village in 2024.

On the banks of Alma al-Chaab, the Israeli border and military posts are less than a mile away and the coast of the Israeli city of Nahariya is visible in the distance. In the other direction is a view of the bright blue waters of Lebanon’s Nakoura Gulf.

Sayah, who is on leave as a maths teacher, says the village has not received much support either from the state – which he says is unable to help anyone – or from the church.

“We love the Lebanese state,” he says. But they should also love us as much as we love them.” He says that even after a year of the ceasefire, they have neither electricity nor water. “We are part of the Lebanese land. We want to stay here.”

He also says he expects more support from the Catholic and Maronite Catholic churches.

“We believed the church needed to help us rebuild,” he says. “They needed to help if they wanted Christians to stay in this area.”

“Your visit, even if brief, will be a profound source of strength for us, a sign that the Church remembers her children on the borders and a message to the world that these lands and their people have not been forgotten,” he said, reading from a letter he wrote to Pope Leo to persuade him to come south.

He says he won’t go to any of the Pope’s events – and neither will many of the village’s residents. Instead they would collect and plant new cedar trees to replace those cut down in the war.

<a href