I was given a year-round puzzle by Palmetto for Christmas last year, and I immediately knew I had to do it.

This is one of those tile puzzles where you have a set of Tetris-like pieces (polyominoes) that you have to fit into a grid – the trick is to only leave 2 cells open that correspond to the day.

It’s a big enough puzzle that I’ll spend 5 minutes in the morning, but not a puzzle I can solve every day! And, whenever I failed, the vengeful little ghost in my brain would get closer to creating a program to take complete control and find Everyone solution for Everyone day, to actually show this laser-cut piece of plywood who’s boss – (and a few days to find out if are really Harder than others or if I get lucky sometimes)

Spoiler, every day Is A different difficulty. Also, I believe that the puzzle could be improved substantially with a small change.

problem formulation

When I started researching how to solve these tiling puzzles the first algorithm I found was Knuth’s Algorithm X.

I didn’t end up using DLX because I was more interested in learning how to use the SAT solver (Z3 is actually an SMT solver, I know), but the problem formulation used by Knuth in DLX made it much easier to set up.

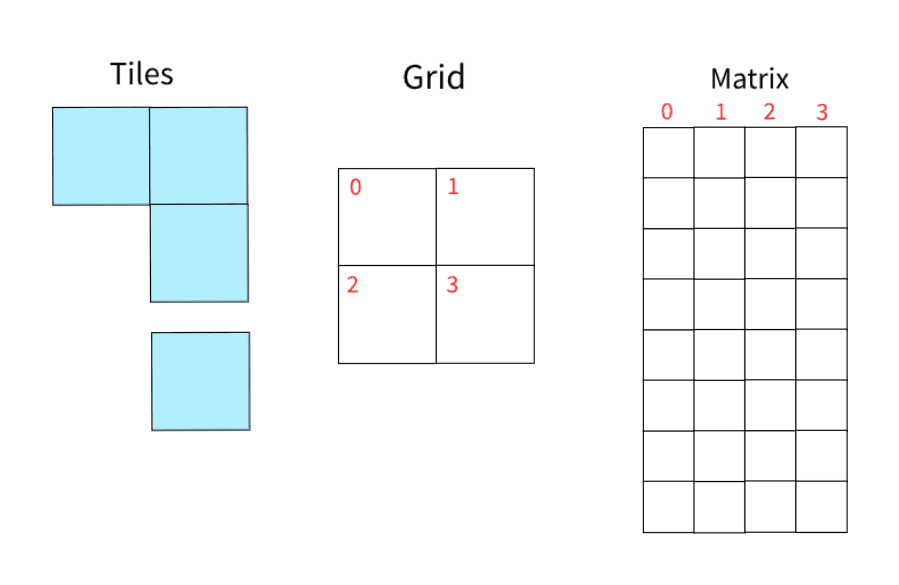

Essentially, we convert the puzzle into a matrix. Each row of the matrix matches Valid placement of polyominoes on empty puzzle

and matches each column a special cell of the puzzleHopefully a picture will help clarify this,

![]()

In this simplified setup, we just need to completely cover a 2×2 puzzle grid with 2 very simple tiles. I have numbered each cell and assigned it a column in the matrix.

![]()

We start filling the matrix by placing the first tile and recording which cells it covers with 1. Also, we need to remember that this first row corresponds to this particular polyomino, but it is not described.

![]()

This process is repeated until all possible polyomino placements have been recorded. Now we have the entire puzzle stored as this matrix.

In this formulation, it is easy to see which polyomino placements can be chosen to cover a particular cell: for example, the 0 cell is covered by all but one placement of the tromino and only one placement of the monomino.

Furthermore, the puzzle is now reduced to choosing the rows of the matrix (choosing the placement of the polyominoes) such that each column is covered exactly once (each cell is covered exactly once). To make sure you only use each tile once, you can either keep track of them separately (which is what I did) or encode the use of each tile with an additional column that is 1 for any placement where it is used.

to Z3

Now, with this matrix in hand, you can easily feed it to DLX and get all the solutions very quickly.

However, if you’re interested in learning about Z3, read on to see how easily we can set it up using this representation.

First, we need to create a solver and a Z3 bool variable for each possible placement.

solver = Solver() # inc_mtx is the numpy array representation of the puzzle placement_bools = [Bool(f"p_{i}") for i in range(inc_mtx.shape[0])]Then, we can iterate over each column of our matrix (each cell of the puzzle), and add a condition to the solver that one of the placements covering it must be used (unless we want to leave that cell open, in which case we don’t need to use any).

for j in range(inc_mtx.shape[1]): # Get all indices with a 1 (placement covers this cell) placement_idxs = np.argwhere(inc_mtx[:,j]).flatten() # Convert indices to associated Bool variables covering_bools = [placement_bools[i] for i in placement_idxs] # Either require exactly 1 or 0 be used depending on the day # j1 and j2 are the columns / cells wanted uncovered today cell_is_today = (j == j1) or (j == j2) solver.add(PbEq( [(v, 1) for v in covering_bools], 0 if cell_is_today else 1) )Finally, we require that each polyomino is not used more than once, that exactly one placement of each polyomino is used.

# poly_is maps polyominos to all the # row-indices of their placements in the matrix for poly, idxs in poly_is.items(): poly_bools = [placement_bools[i] for i in idxs] solver.add(PbEq([(v, 1) for v in poly_bools], 1))And that’s all! now we can just call solver.check() And solver.model() To find solutions any day of the year!

But, if you want to enumerate all solutions, you will have to repeatedly ask Z3 to find new solutions, such as by adding new constraints:

while solver.check() == sat: model = solver.model() n_solns += 1 # Require next solution to be different # in at least 1 variable than this one not_last_soln = Or([v != model[v] for v in placement_bools]) solver.add(not_last_soln)Result

To see how difficult each day is, I logged the number of solutions for each day of the year calplotin which fewer solutions (more difficult puzzles) are red, and more solutions are blue

As you can see, every day is different. Also, the main factor of difficulty is the month.

Improvement

Not satisfied, as there is no easy way to explain how difficult a puzzle each day is, I became curious to know whether a different arrangement of the underlying months and days would yield a more satisfying plot.

So, I calculated all the solutions for all the pairs (this is where using DLX would have saved me half an hour of waiting) and sorted them, and came up with the following arrangement:

This system places the months on increasingly difficult cells by interpolating them from easiest to hardest. For days, I put them in the easiest-difficult arrangement for January, although other sorting can lead to a steady increase in difficulty each month. Here are the results:

I’ll let you decide whether this decidedly much less intuitive arrangement of days is worth the knowledge that the puzzle you’re solving becomes more difficult every day.

That is all! If you want to see my code you can find the full notebook here on my Github.

Thanks for reading!