A severe loss in short-term kidney function, known as acute kidney injury (AKI), can be life-threatening and may also increase the chance of developing permanent chronic kidney disease. AKI can occur after sepsis or major stress such as heart surgery, and more than half of all intensive care patients experience it. There are currently no approved medications to treat this condition.

Researchers at the University of Utah Health (U of U Health) have discovered that fatty molecules called ceramides trigger AKI by damaging the mitochondria that supply energy to kidney cells. Using a backup drug candidate designed to alter the way ceramides are processed, the team protected mitochondrial structure and prevented kidney injury in mice.

“We have completely reversed the pathology of acute kidney injury by inactivating ceramides,” says Scott Summers, PhD, distinguished professor and chair of the Department of Nutrition and Integrative Physiology at the University of Utah College of Health and senior author of the study. “We were stunned – not only did kidney function remain normal, but the mitochondria were also preserved,” says Summers. “It was truly remarkable.”

Results have been published cell metabolism,

Ceramide spikes may serve as an early warning

Earlier studies from the Summers lab have shown that ceramides can harm organs such as the heart and liver. When researchers measured ceramides in an AKI model, they found a strong relationship: levels increased rapidly after injury in both mice and human urine samples.

“Ceramide levels are greatly increased in kidney injury,” says Rebekah Nicholson, PhD, first author of the work, who completed the research as a graduate student in nutrition and integrative physiology at U of U Health and is now a postdoctoral fellow at the Arch Institute. “They increase rapidly after kidney damage, and they increase in relation to the severity of the injury. The worse the kidney injury, the higher the ceramide levels.”

These findings indicate that urinary ceramides may act as an early biomarker for AKI, giving physicians a tool to identify vulnerable patients, including those preparing for cardiac surgery, before symptoms begin. “If patients are undergoing a procedure that we know puts them at higher risk of AKI, we can better predict whether they’re actually going to get AKI or not,” says Nicholson.

Modulating ceramide production protects kidney function

The team virtually eliminated kidney injury in a mouse model by modifying the genetic program that controls ceramide production. This mutation produced “super mice” that did not develop AKI, even under conditions that normally cause severe damage.

The researchers then tested a ceramide-reducing drug made by Centaurus Therapeutics, a company co-founded by Summers. The mice treated prematurely did not suffer kidney damage, their kidneys continued to function normally, remained active, and their kidneys appeared close to normal under the microscope. Nicholson notes that his model places extreme stress on the kidneys, making it “truly remarkable that the mice were spared from injury.”

“These rats looked incredible,” says Summers.

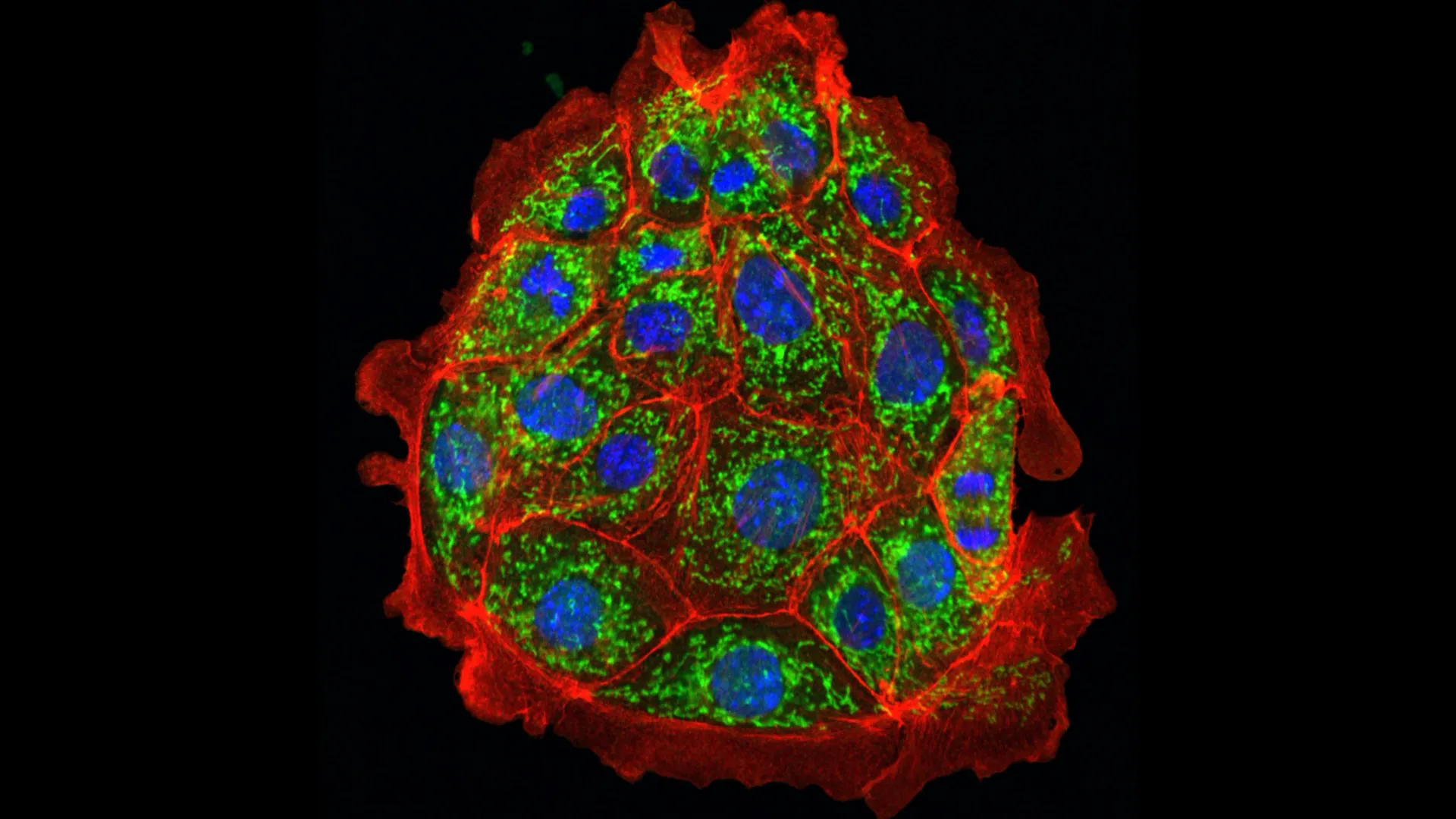

The team found that ceramides damage mitochondria, which are the parts of the cell responsible for energy production. Damaged mitochondria in kidney cells become distorted and function poorly. Adjusting ceramide production, whether genetically or with medication, kept mitochondria intact and functioning even under stress.

Potential for future therapies targeting mitochondrial health

Summers points out that the compound used in this study is closely related, but not identical, to a ceramide-reducing drug entering human clinical trials. He emphasizes that results in mice do not always predict human outcomes and that more research is needed to confirm safety.

“We are thrilled with how protective this backup compound was, but it is still preclinical,” Summers says. “We need to be cautious and do our due diligence to make sure this approach is truly safe before implementing it on patients.”

Still, researchers are encouraged by the findings. If the results extend to people, the drug could potentially be given prematurely to individuals who face a higher risk of AKI, including patients undergoing heart surgery, where about a quarter experience the condition.

Because the drug appears to work by maintaining mitochondrial health, the team believes this approach may be relevant to other disorders associated with mitochondrial dysfunction.

“Mitochondrial problems appear in many diseases — heart failure, diabetes, fatty liver disease,” says Summers. “So if we can really restore mitochondrial health, the implications could be huge.”

The results are published in Cell Metabolism as “Therapeutic remodeling of the ceramide backbone prevents kidney injury.”

Funding and disclosures

This work was supported by the NCRR Shared Equipment Grant, the Kidney Precision Medicine Project, and several branches of the National Institutes of Health, including the National Cancer Institute (P30CA042014, CA272529), the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (DK115824, DK116888, DK116450, DK130296, DK108833, DK112826, 1F31DK134088 and 5T32DK091317), and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (3R35GM131854 and 3R35GM131854-04S1). Additional support was received from the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation (JDRF 3-SRA-2019-768-AB and JDRF 3-SRA-2019-768-AB to WLH), the Burroughs Wellcome Fund Postdoctoral Diversity Enrichment Program (1058616), the American Diabetes Association, the American Heart Association, the Margolis Foundation, and the University of Utah Diabetes and Metabolism Research Center. The authors state that the content is their responsibility and does not necessarily reflect the views of the National Institutes of Health.

Scott Summers and Jeremy Blitzer are co-founders and shareholders of Centaurus Therapeutics. Liping Wang is also a shareholder. DN and Blitzer are listed as inventors on US patents 1177684, 11597715, and 11135207, which are licensed to Centaurus Therapeutics, Inc. Is licensed.