Two years after banning student cell phones, student test scores in a large urban school district were significantly higher than before, according to David N. Figlio and Umut Ozack find in The Impact of Cell Phone Bans in Schools on Student Outcomes: Evidence from Florida (NBER Working Paper 34388). The study examines data from a large urban county-level school district in Florida, one of the 10 largest school districts in the United States. While Florida statewide law bans the use of cell phones during instructional time, this district implemented a strict policy requiring students to keep phones on silent and stored in backpacks throughout the school day, including lunch and transitions between classes.

Two years after banning student cell phones, student test scores in a large urban school district were significantly higher than before, according to David N. Figlio and Umut Ozack find in The Impact of Cell Phone Bans in Schools on Student Outcomes: Evidence from Florida (NBER Working Paper 34388). The study examines data from a large urban county-level school district in Florida, one of the 10 largest school districts in the United States. While Florida statewide law bans the use of cell phones during instructional time, this district implemented a strict policy requiring students to keep phones on silent and stored in backpacks throughout the school day, including lunch and transitions between classes.

An all-day cell phone ban in a Florida school district improved test scores, especially among male students and in middle and high schools.

The researchers combined the two datasets to conduct this analysis. First, they accessed student administrative data for the year before the ban (AY 2022-23) and two years after the ban (AY 2023-24 and AY 2024-25). These data are reported to the district three times annually and include information on student demographics, attendance, disciplinary actions, and standardized test scores. Second, they examined building-level smartphone activity data from Advan for district schools. This data tracked the average number of unique smartphone pings between 9am and 1pm during the school day. To isolate the effects of student usage, the team compared normal school days only to professional work days. They then compared the last two months of AY 2022-23 (before the ban) with the first two months of AY 2023-24 and AY 2024-25 (after the ban) and found an average decline in usage of about two-thirds. The relative level of reduction in use was used to sort district schools into high-impact (top tercile of pre-ban use) and low-impact (bottom tercile of pre-ban use) pools.

During the first month of the ban (September 2023), student suspensions increased 25 percent compared to the same month last school year. The increased disciplinary rates continued throughout the school year. The effects were particularly severe among black male students, whose in-school suspension rates increased by 30 percent in heavily affected schools. However, even in the most affected schools and population groups, the rate of disciplinary actions fell to near pre-ban levels by the beginning of the next school year. Researchers believed this represented a period of adjustment to the new policy rather than an indication of long-term negative effects of the ban’s implementation.

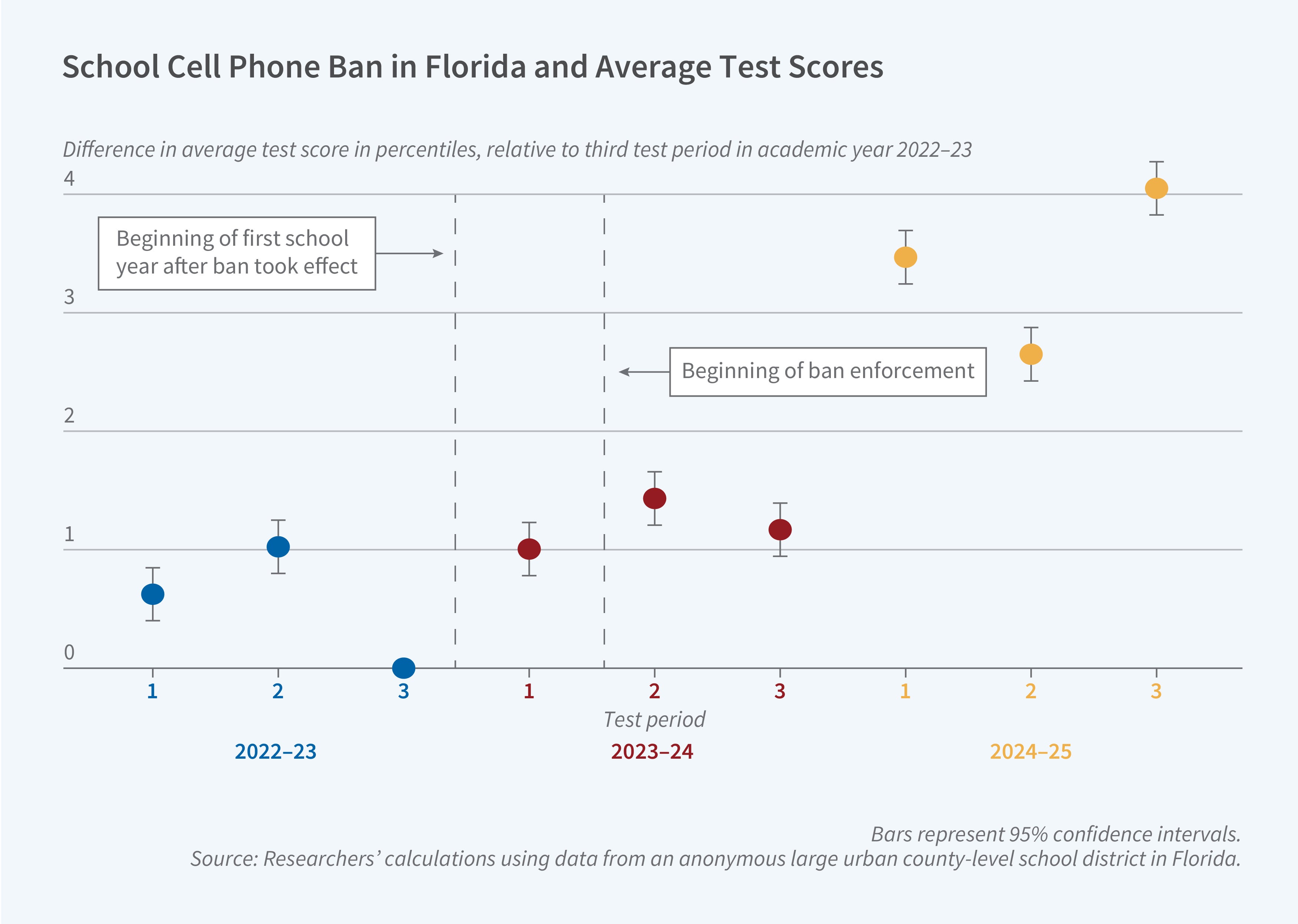

During the first year of the ban, when disciplinary rates were high, there were no statistically significant changes in test scores. In contrast, during the second year of the ban, test scores increased significantly, with the positive effects concentrated during the spring semester (scores increased by an average of 1.1 percent). Researchers suggest this may be due to higher exposure to spring tests, which can impact grade advancement and high school graduation. The improvement in test scores was also concentrated among male students (up 1.4 percent on average) and middle and high school students (up 1.3 percent on average).

When comparing high-impact and low-impact schools, researchers found a significant reduction in unexcused absences during the two years following the cell phone ban. They believe that increased attendance could explain half the improvement in test scores noted in their primary analysis.

-Emma Salomon

The researchers thank the Smith Richardson Foundation for generous research funding.

<a href