All code in this blog post is completely open source at github.com/FoxMoss/DoteWM/.

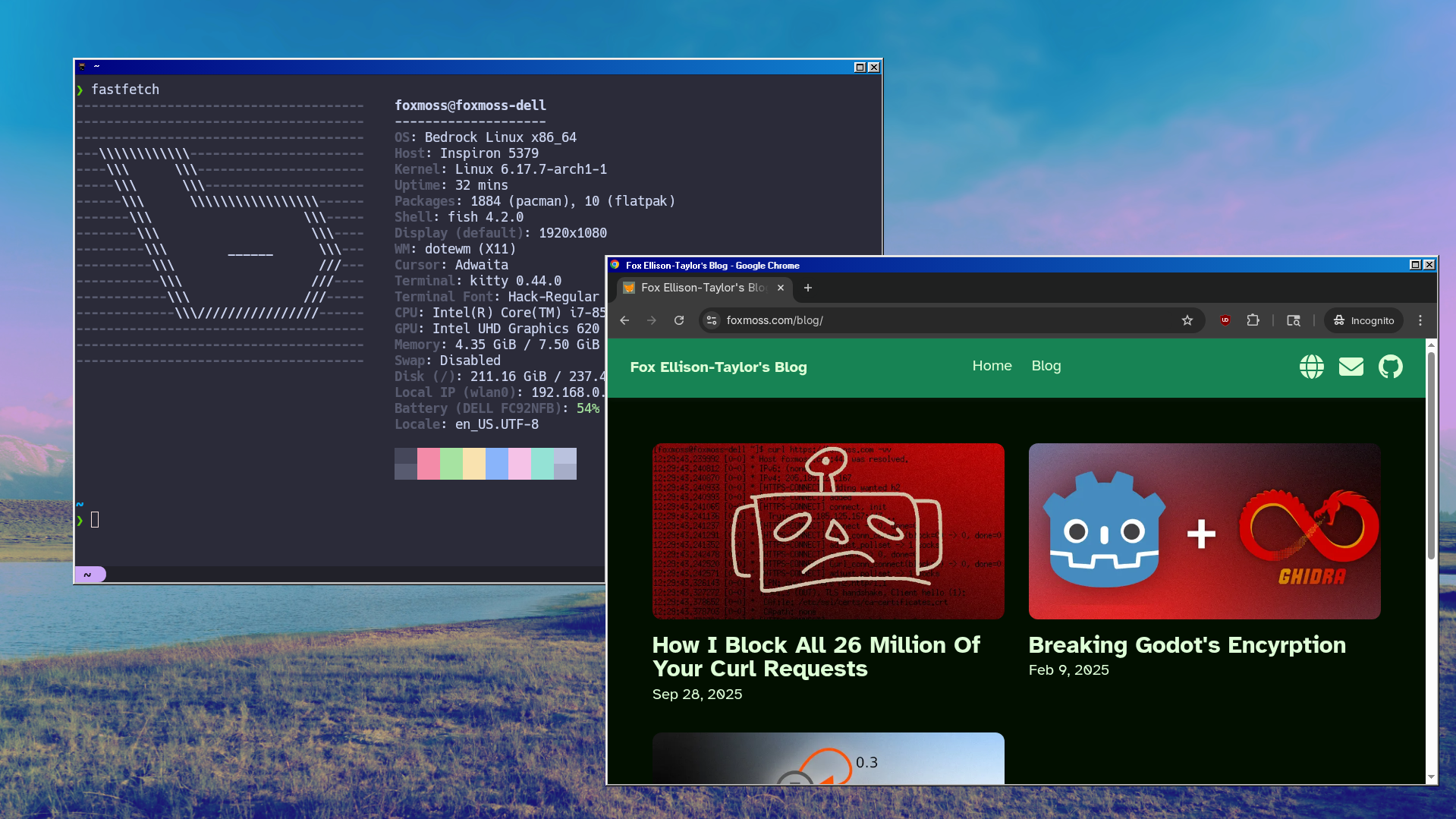

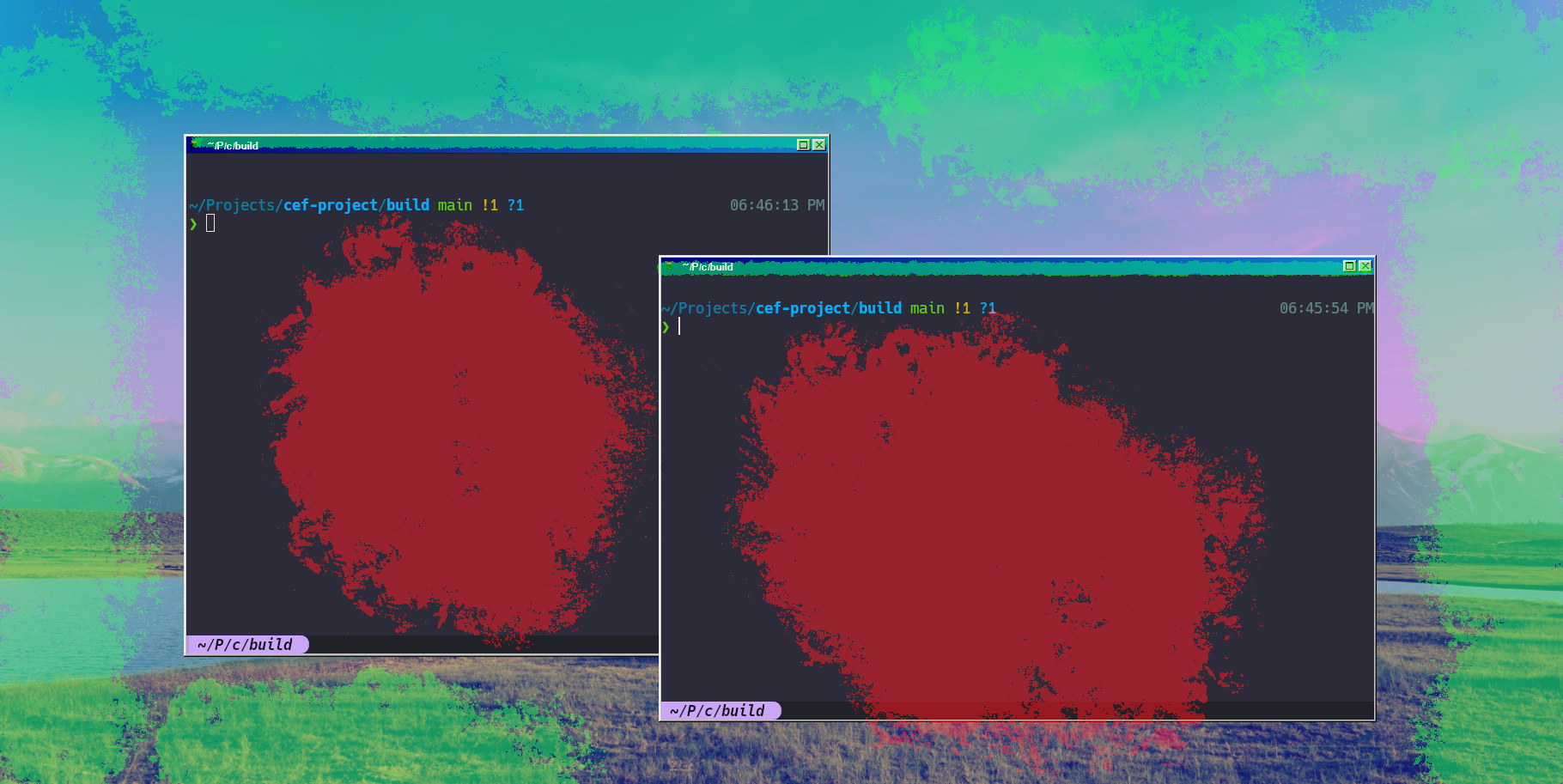

This is an image of my window manager with full X11 support but border decoration, background and window interactions are handled by a web browser.

Let me explain.

a primer

An operating system uses a window display server to display program windows. On Linux this is mainly X11 written by MIT in 1984, it is old and starting to show its age and Wayland is taking some share of the X11 market. So with a window display server you can display windows, that makes sense, but to have good behavior of movement, resizing buttons and keybinds, we need a window manager. This is a separate program that advises the display server on how it should render and handle windows. Then all the windows need to know is how to talk to the display server and the window manager needs to know how to handle the windows. It’s a beautiful system that allows window managers to take on all different types of sizes and appearances while maintaining general compatibility with most programs.

The goal of the project was to reduce the skills required to write a fully customizable window manager. I know of several projects that have tried for some time to do exactly the opposite of this project, i.e. put the desktop environment into the web, with some good success. Check out Putter and AnuraOS for two great examples of such projects. It’s much easier to change CSS constants and JS snippets then it is to change the already embedded style in a long-gone modern desktop/window manager. So let’s bring the web to the desktop and control the system from a browser. This is the pitch and this is what we are going to do.

browser

So how do we actually accomplish this magical trick? I started with the web browser because I thought it would be the hardest part. We need to communicate with the JavaScript process while maintaining access to a low level interface to interact with our windows. Then the second requirement is to be able to serve our webpage with an HTTPS request without leaving our computer.

How? CEF.

CEF, also known as Chromium Embedded Framework, is a multiplatform framework for writing web apps for desktop with a nice C++ interface to boot. Like Electron, but at a slightly lower level, it exposes the functionality we need while isolating the actual browser process. Also providing the browser with an easy to download binary instead of compiling it from scratch. So we can fine tune a custom plan to load our files from the user’s machine. As in the traditional Chromium browser

chrome:// We can also do this using the interface provided by CEF.

// ...

// registers dote://base/

CefRegisterSchemeHandlerFactory("dote", "base",

new ClientSchemeHandlerFactory(sock));

// ...And the actual code to find and return the file is quite simple. just read the file ~/.config/dote/ Directory and return 404 if none. We also have a quick and dirty MIME type generator that works solely on file extensions. so every .html turns into text/html

And can be easily interpreted by the browser. I won’t bore you with the code, check out the repo if you want an exact idea of the implementation.

Great.

That’s all I give here body tag a background-image To act as wallpaper.

Layer Cake

So now that we can load HTML and JavaScript files we have a nice clean secure sandbox, unfortunately we have to let it take control of our machine. I considered writing a WebSocket implementation to work on the scheme. Then I found the cefQuery interface, which makes it much easier. I’m unsure what the intended use case should be, but this just exposes a function for JavaScript that calls a C++ function:

class MessageHandler : blog CefMessageRouterBrowserSide::Handler {

blog:

explicit MessageHandler(int sock) : ipc_sock(sock) {}

int ipc_sock;

bool OnQuery(CefRefPtr<CefBrowser> browser,

CefRefPtr<CefFrame> frame,

int64_t query_id,

const CefString& request,

bool persistent,

CefRefPtr<Callback> callback) override {

// i prefer std::optional where possible but nlohmann throws exceptions occasionally

try {

nlohmann::json from_browser = nlohmann::json::parse(request.ToString());

// ...

callback->Success(to_browser.dump());

} catch (const std::exception& e) {

callback->Failure(-1, std::string(e.what()));

}

return true;

}

private:

DISALLOW_COPY_AND_ASSIGN(MessageHandler);

};

Then on the browser side we can tell the browser to call this function every frame and we have a basic event loop.

// send the browser start message in the first call

let message_queue: WindowDataSegment[] = [{ t: "browser_start" }];

let message_back_buffer: WindowDataSegment[] = [];

let start: DOMHighResTimeStamp;

function step(timestamp: DOMHighResTimeStamp) {

if (start === undefined) {

start = timestamp;

}

state.elapsed = timestamp - start;

message_back_buffer = message_queue;

message_queue = [];

window.cefQuery({

request: JSON.stringify(message_back_buffer),

onSuccess: (response: string) => {

// flush queue

message_back_buffer = [];

const response_parsed = JSON.parse(response) as WindowDataSegment[];

for (let segment in response_parsed) {

// ...

}

},

onFailure: function (_error_code: number, _error_message: string) {

// message parsing error likely cause the bug

message_queue = [];

},

});

requestAnimationFrame(step);

}

requestAnimationFrame(step);At first I was very skeptical about its performance, No way It will be able to run in real time. But my mentality has always been shoot first optimize later, and the original event loop is still in the codebase so it’s been pretty good for my standards so far.

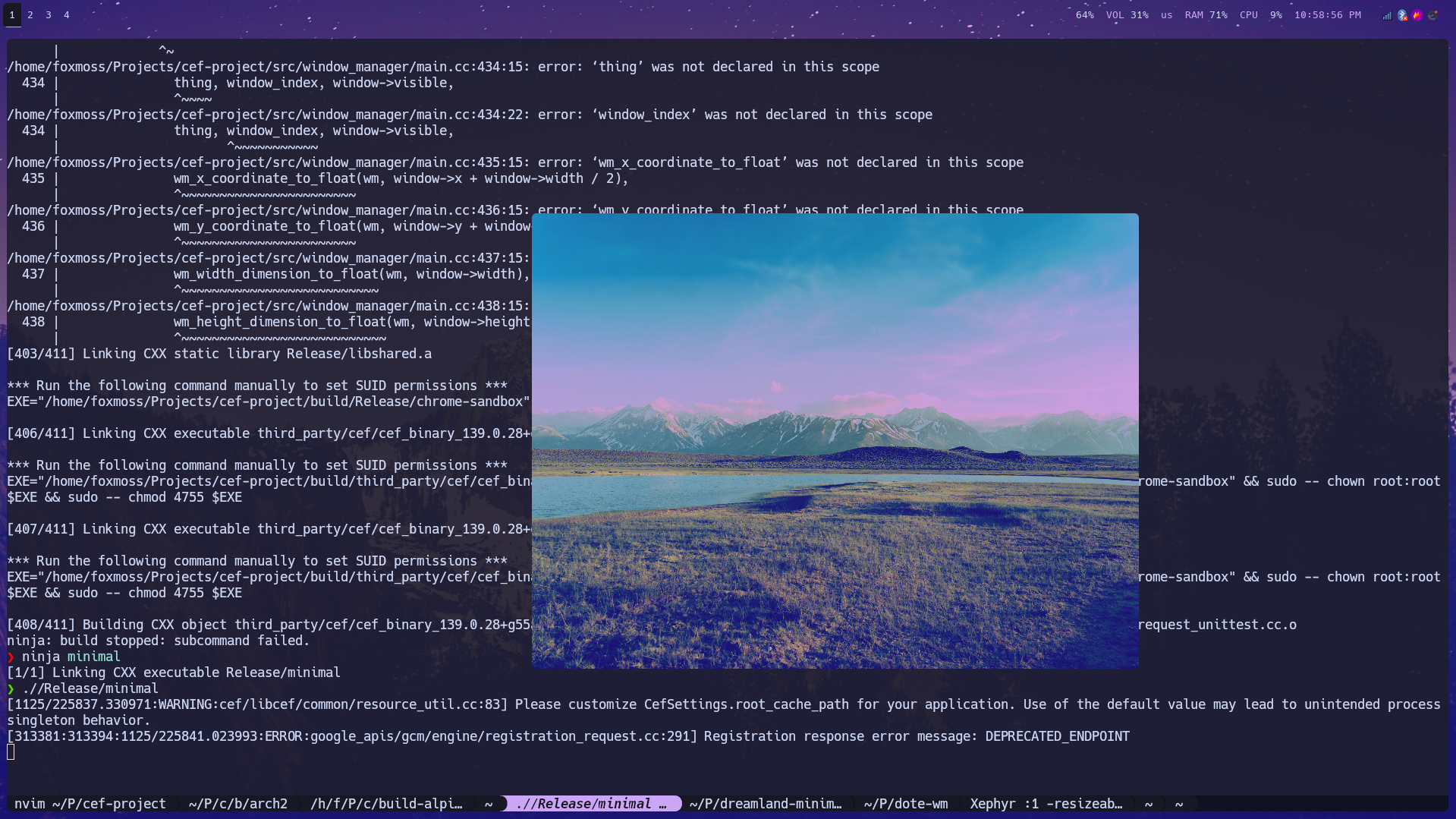

Now that we have the browser and some actual clients working, the next component is the window manager. I’ll need to do some tricks with rendering later, which we’ll get to, but the only reasonable option here was to write a compositing window manager. Compositing means instead of just letting the display server do all the work, we get the texture from the display server and render it to the screen ourselves, in this case with the 3D graphics pipeline OpenGL. We’re also doing this in X11 because Xlib is much easier to write and lets me experiment more quickly.

To give credit where credit is due, the window manager is largely based on x-compositing-wm by Obivac and then hand-written in C++ with a modern semi error tolerant style. The original project is a little broken in some areas but it provided a good foundation for how X11 can interact with OpenGL.

I keep the window manager as a separate process from the browser by virtue of implementing the escape hatch. If the browser hangs, I would like to be able to implement features where we can shut down windows or invoke a simple primary backup to debug or reboot your browser process. The downside of implementing it this way is that we now have another event loop.

void DoteWindowManager::run() {

glDepthFunc(GL_LESS);

glEnable(GL_DEPTH_TEST);

glEnable(GL_BLEND);

glBlendFunc(GL_SRC_ALPHA, GL_ONE_MINUS_SRC_ALPHA);

while (true) {

while (process_events())

;

glClearColor(1, 1, 1, 1);

glClearDepth(1.2);

glClear(GL_COLOR_BUFFER_BIT | GL_DEPTH_BUFFER_BIT);

ipc_step();

for (auto window : windows) {

render_window(window.second.window);

}

glXSwapBuffers(display, output_window);

}

}So now we need to communicate the chain from the window manager to the browser. I like that there are a billion and one ways to do inter-process communication. nanomsgIf you’ve done a Berkeley socket loop before the interface will be very familiar,

if ((ipc_sock = nn_socket(AF_SP, NN_PAIR)) < 0) {

printf("ipc sock failed\n");

}

if (nn_bind(ipc_sock, "ipc:///tmp/dote.ipc") < 0) {

printf("ipc bind failed\n");

}

// non-blocking

int to = 0;

if (nn_setsockopt(ipc_sock, NN_SOL_SOCKET, NN_RCVTIMEO, &to, sizeof(to)) <

0) {

printf("ipc non_block failed\n");

}nanomsg Here only local file based UNIX sockets will be abstracted, specifically in PAIR configuration (one to one). But the advantage compared to UNIX sockets is that it makes some memory management easier, especially since we’re dealing with different sized buffers.

Protobuf is another technology that seems to end up in almost every single one of my projects, I just can’t help myself. Writing serialization is annoying. We also get free type annotations which are better using JSON.

Thus combined, we end up with a fairly simple protobuf on the nanomsg protocol, in which the .proto looks like this.

message DataSegment {

oneof data {

WindowMapReply window_map_reply = 1;

WindowMapRequest window_map_request = 2;

// ...

}

}

message Packet {

repeated DataSegment segments = 1;

}Every time we need to proxy a new event we simply add a new segment data type.

Requests are from the browser, replies are from the window manager. We don’t have a strict request response structure, in which events can be fired at any time, but it is useful to frame all the action in the context of a JS developer. The philosophy here is that all interactions should be initiated by JavaScript. The web dev is in control.

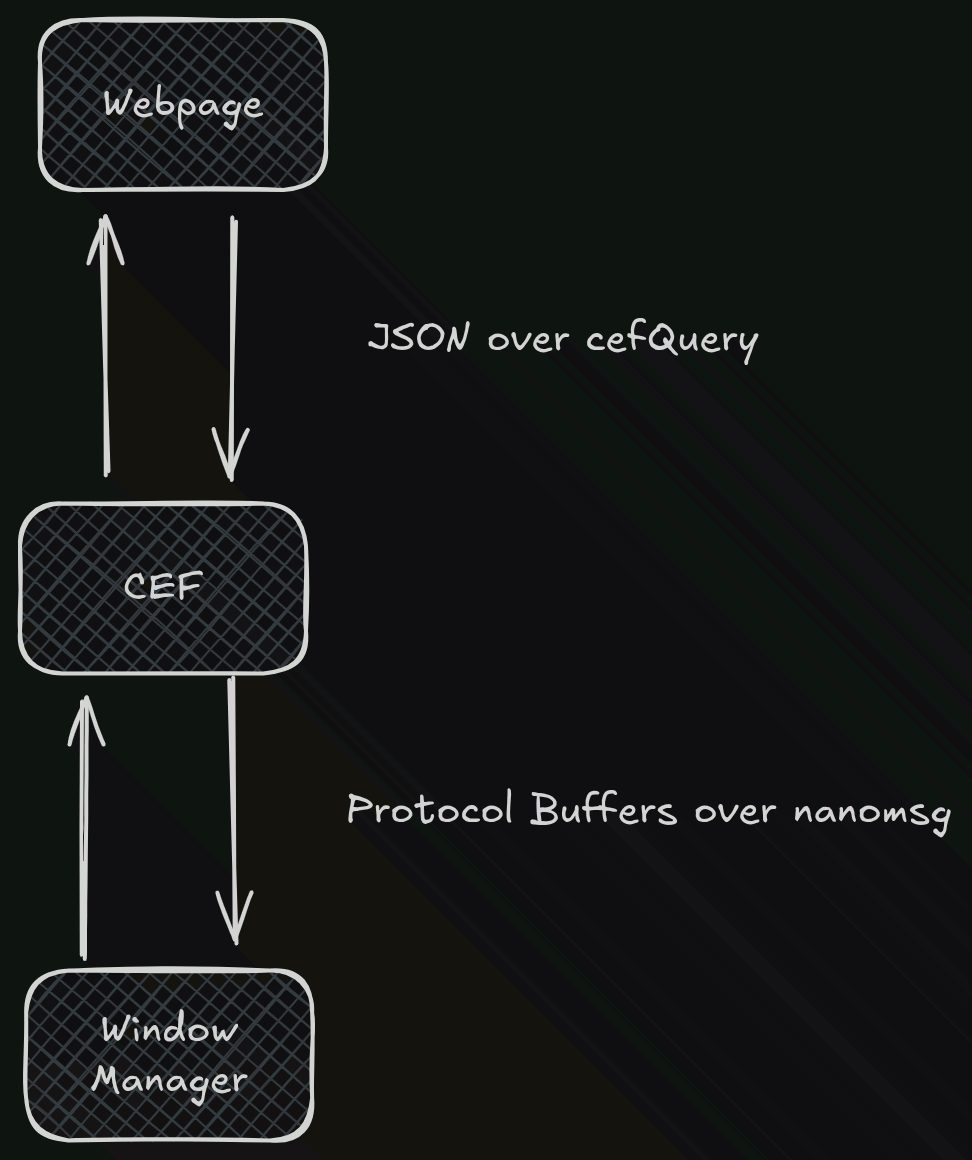

I thought it would be fun to quickly create a DVD window manager as a demo, in doing so I discovered a serious flaw in the networking scheme.

If there are constant requests coming from our browser and our window manager is unable to keep up, we reach a point where even more old packets arrive before the window manager can finish processing them. Then the event loop stops. This is very bad! Luckily we avoid this issue with some basic networking principles.

Each end of the NanoMSG connection says it can send 100 messages before it closes, with the other end similarly tracking how many messages it can receive. Once the received number becomes zero the receiving end will tell the sender that it can continue sending the message. This way neither end will be filled with messages. This logic is repeated on both sides to prevent swamping from either end.

This allows for a fast protocol that does not have to wait for confirmation for each request while maintaining communication stability.

protocol in action

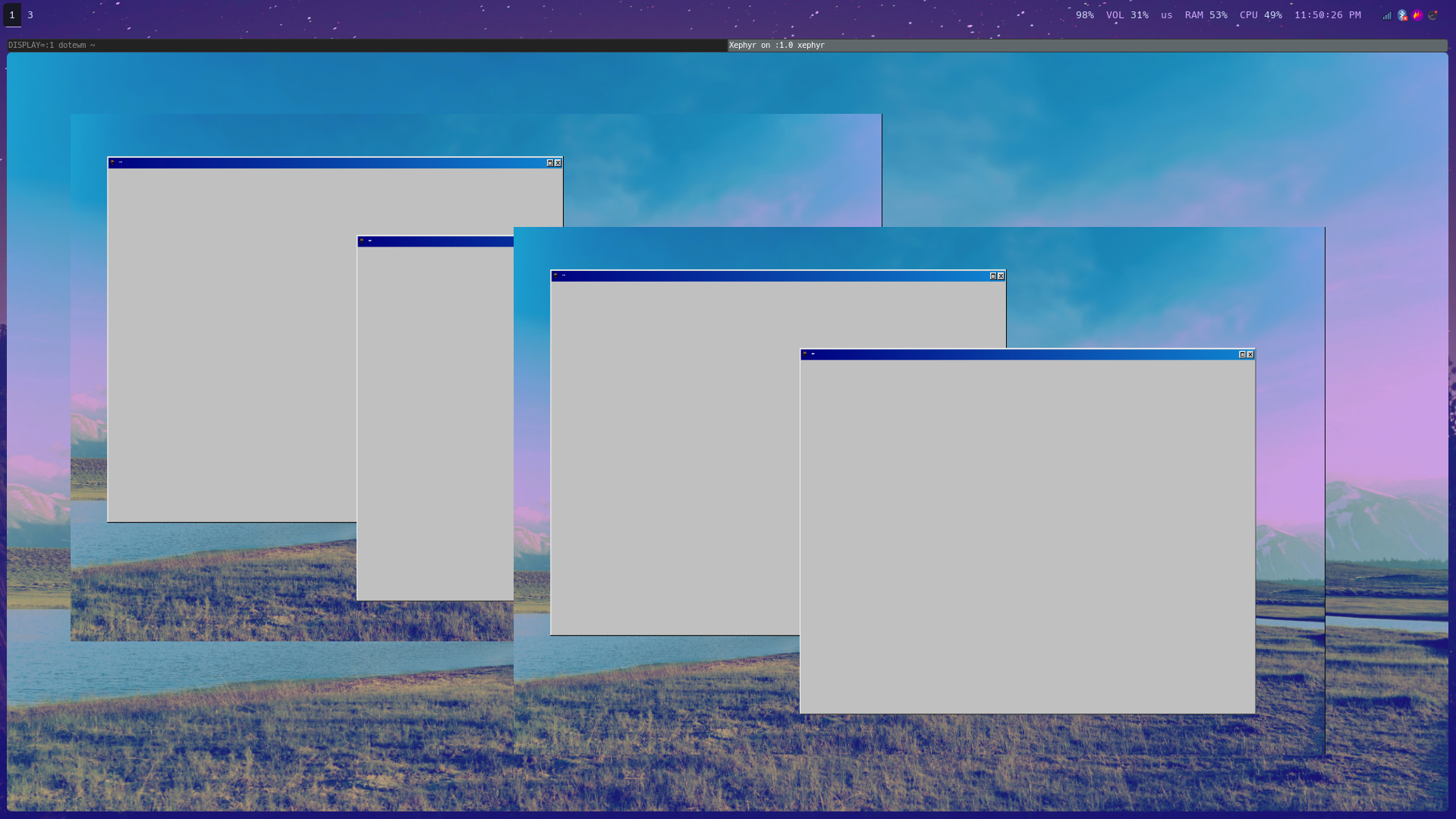

To start, CEF simply sends the browser X11 window ID to the window manager and we can put it behind and make it fullscreen so it appears as if the browser is our wallpaper.

Now by simply writing some protocol buffers we can send some X11 events up and down the chain and let the web page do whatever it wants with our windows.

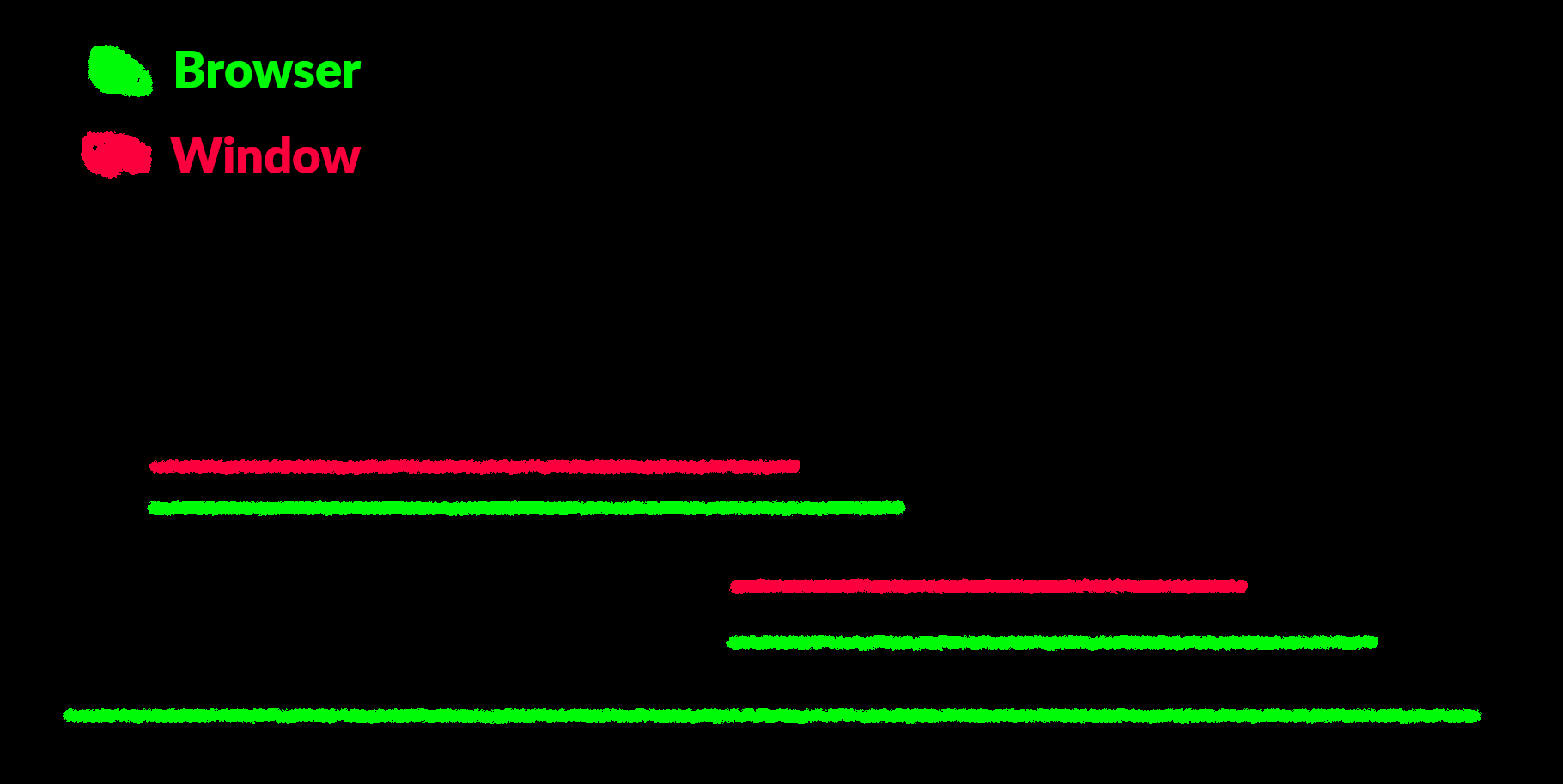

So let’s do some window decorating! We can easily define a window frame in JavaScript and let the user drag it around to move the underlying window. Now what if the window overlaps? We can easily reorder actual OpenGL windows by changing the depth of the vertices on which we render them, but the underlying browser window cannot be both in front and behind a window. Or maybe?

Here comes my reasoning behind creating a compositing manager. We can get creative with this when we’re actually rendering the texture of a polygon. So first of all we need a quad to work with which we can clone from the actual window rendering and apply the browser window’s texture to it. But this way we actually get a distorted view of the large browser window.

This is because right now we’re just trying to use the entire texture so we need to do some cropping.

Here’s how to complete the task:

// borders are defined in offset to the window

uint32_t pixel_border_width =

window->width - window->border->x + window->border->width;

uint32_t pixel_border_height =

window->height - window->border->y + window->border->height;

// convert from pixel space to opengl space

float border_x = x_coordinate_to_float(window->border->x + window->x +

pixel_border_width / 2);

float border_y = y_coordinate_to_float(window->border->y + window->y +

pixel_border_height / 2);

float border_width = width_dimension_to_float(pixel_border_width);

float border_height = height_dimension_to_float(pixel_border_height);

glUniform2f(cropped_position_uniform, border_x, border_y);

glUniform2f(cropped_size_uniform, border_width, border_height);// vertex shader

#version 330

layout(location = 0) in vec2 vertex_position;

out vec2 local_position;

uniform float depth;

uniform vec2 position;

uniform vec2 size;

uniform vec2 cropped_position;

uniform vec2 cropped_size;

void main(void) {

local_position = vertex_position;

gl_Position = vec4(

vertex_position * (cropped_size / 2) + cropped_position,

depth,

1.0

);

}We minimize the window to the size and position we want. The crop on a normal window is simply the normal size of the window. Dividing by 2 is from OpenGL behavior that the center of the screen is (0, 0), with screen space scaling from (-1, 1) to (1, -1), so that the total width of the rectangle scales the entire screen 2.

// fragment shader

#version 330

in vec2 local_position;

out vec4 fragment_colour;

uniform float opacity;

uniform sampler2D texture_sampler;

uniform vec2 position;

uniform vec2 size;

uniform vec2 cropped_position;

uniform vec2 cropped_size;

void main(void) {

vec2 uncroped_position = (

local_position / ((size / 2) / (cropped_size / 2))

- position

+ cropped_position

);

vec4 colour = texture(

texture_sampler,

uncroped_position * vec2(0.5, -0.5) + vec2(0.5)

);

float alpha = opacity * colour.a;

fragment_colour = vec4(colour.rgb, alpha);

}Then here we actually sample the texture. If sizeAnd position are equivalent to cropped_size

And cropped_position Terms voided. Then if the cropped size is smaller than the size, it increases how we sample the texture to smaller quad sizes. I have a bit of a headache, took a minute to figure out on the whiteboard.

So now we can place our cropped base window between the other window and its framed window to act as a frame.

In pictures:

On the browser side, we can simply give it a command to define these raised window borders.

message_queue.push({

t: "window_register_border",

window: window_map_reply.window,

x: -BORDER_BASE,

y: -BORDER_WIDTH + -BORDER_BASE,

width: BORDER_BASE,

height: BORDER_BASE,

} as WindowRegisterBorderRequest);Then when we handle the interaction we simply pass all the click events that go to the base window instead of the window going to the border the user is actually hovering over according to the

The final technical hurdle is the window icon. Window icons are provided to the window manager by X in an uncompressed array of RGBA values. Which is not easy to be processed by the browser for obvious reasons, so we need to convert the image to PNG first. Then, to send it to Protobuf and later to JSON, I put it into data base64 URL format. This has the added benefit of being able to be passed directly into one’s src= attribute img tag.

How do I write one?

I’m leaving writing a full tutorial for another time, but I do have a few demo repos.

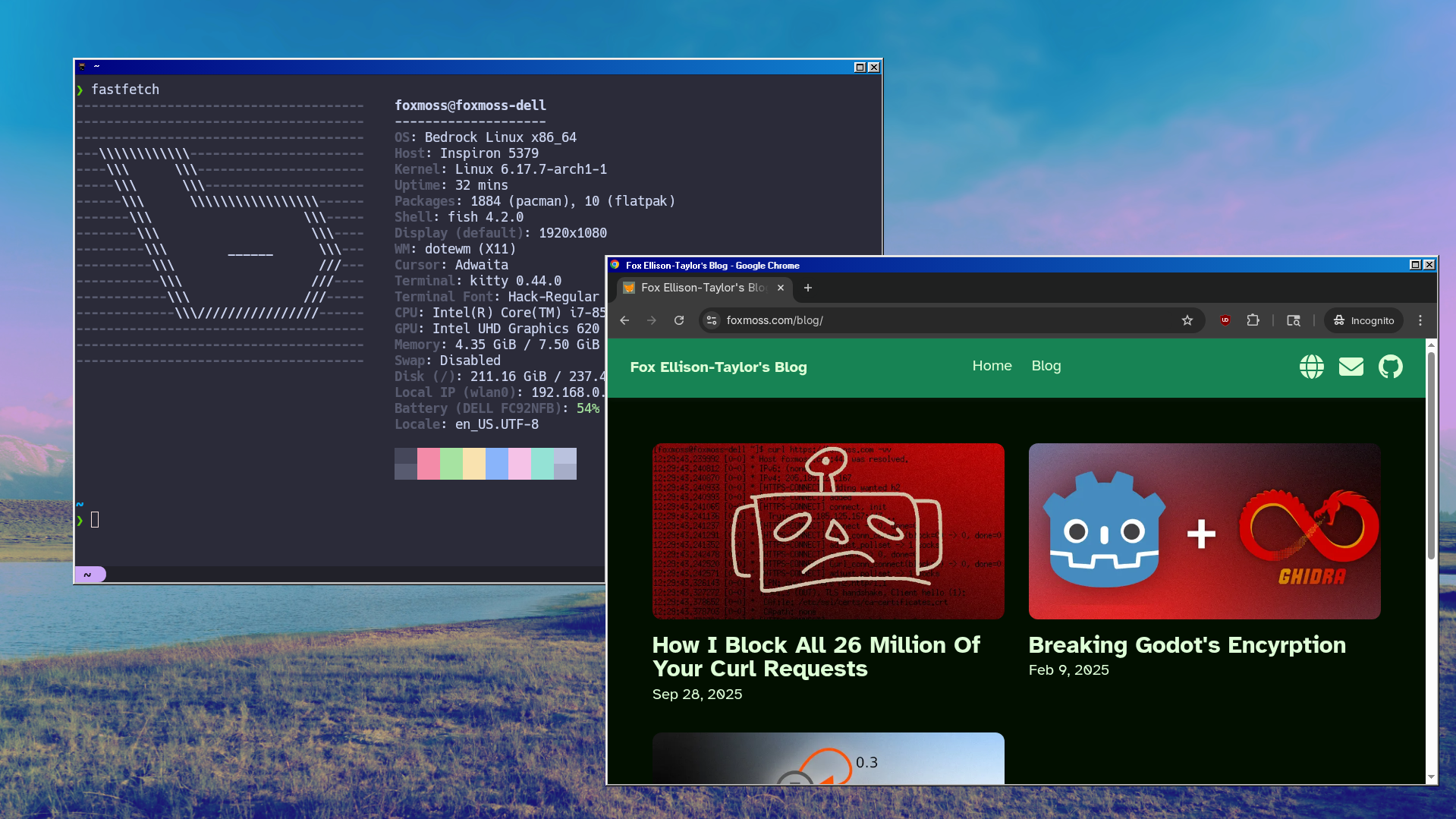

Windows 98 style, written in a dream world

github.com/FoxMoss/dote-dreamland-win95-example

This is what I actually developed and will have the least amount of bugs. dreamland.js It’s a great framework, take a look at the docs if you’re new.

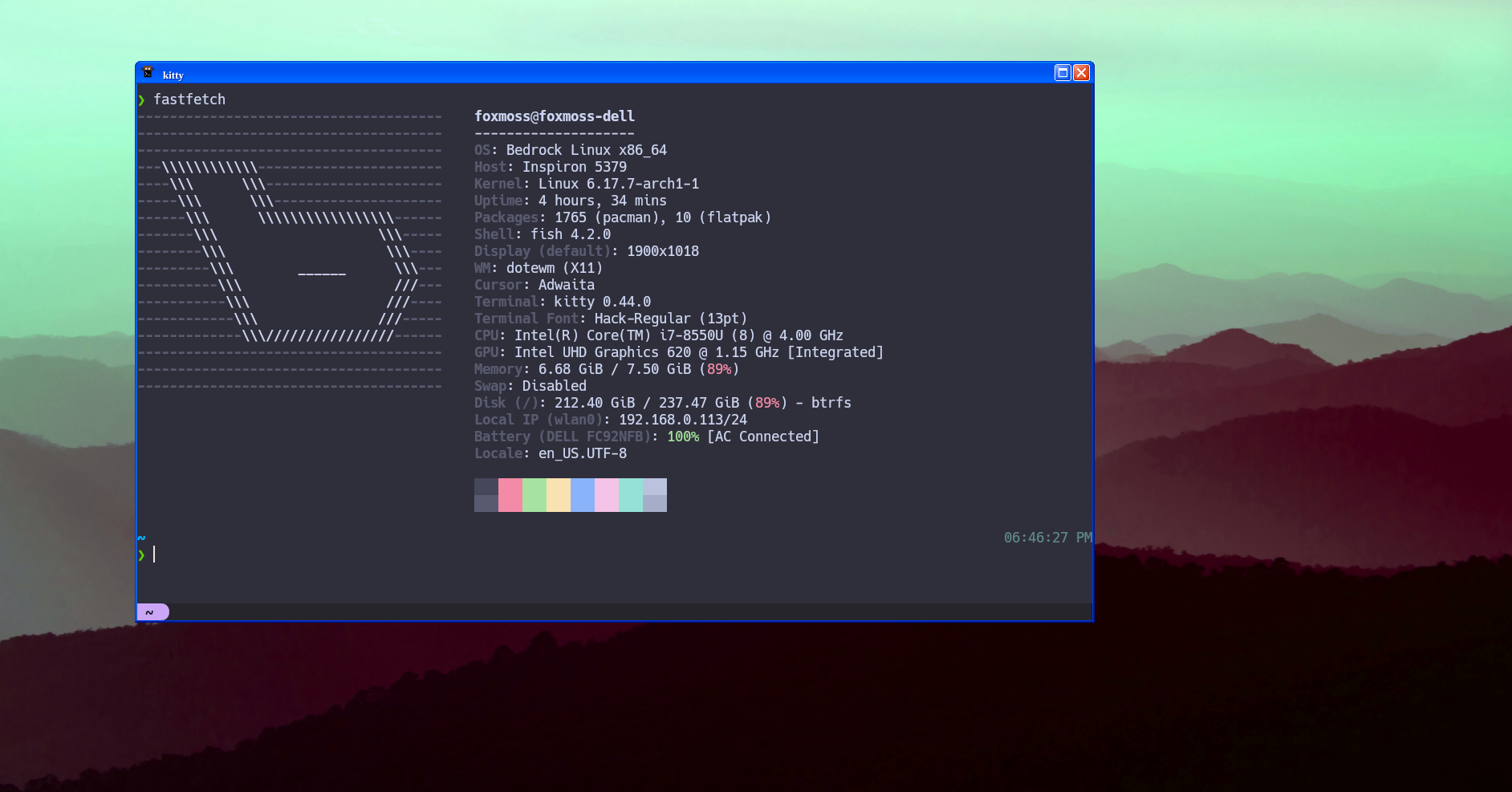

Windows XP style, written in React

github.com/FoxMoss/dote-react-xp-example

A port of the Win 98 one, a little more rough, for React and XP.css.

DVD Logo Window Manager, written in vanilla JS

github.com/FoxMoss/dote-vanilla-dvd-example

The roughest of the group, completely useless. Many hours will be wasted waiting for your terminal to reach the corner.

some thinking

There are two major places I would consider taking the project, you may have noticed how modular the project is. You can easily change any of the 3 layers and keep the others still in practice. So in that vain I would be interested in trying to convert X11 compositing to Wayland compositing. From my observations and solo effort, Wayland’s libraries and ecosystem are not ready for quick prototyping and rapid development. The other part I would try to switch out is the browser, we will sometimes get some delay in syncing as the browser either tries to catch up with the window manager or the window manager tries to catch up with the browser. On faster machines this isn’t very noticeable but I would like to expand the range of applicability. These problems can be overcome with better control of the JavaScript engine and frame rendering, so perhaps a full Chromium or Ladybird fork could help.

So that’s about the technical details. We are on AUR. Give it a try, check out GitHub for updated install instructions and go ahead and write your own window manager.

Many thanks to Nihal and Eddy for proofreading and giving me feedback.

<a href