Measuring cognitive performance in real world settings

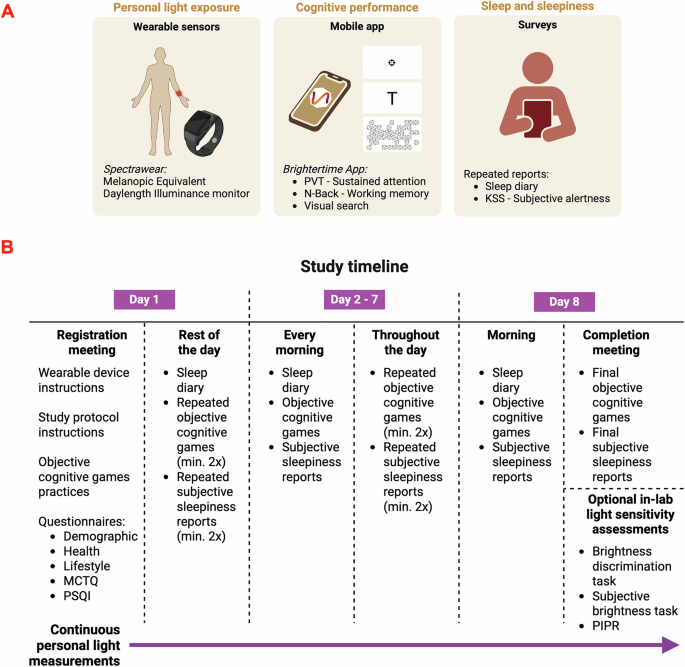

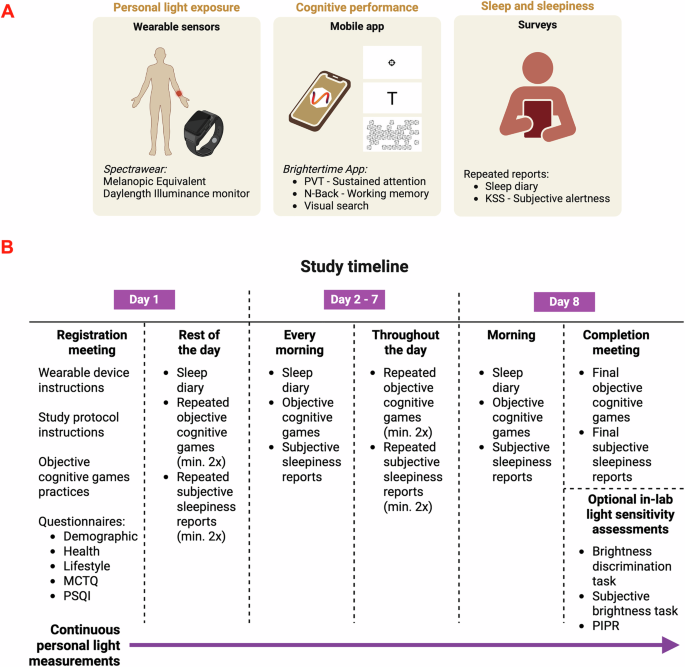

We aimed to collect cognitive function data in everyday life using an accessible smartphone app, Brightertime39. This app incorporates a Psychomotor Vigilance Task (PVT) to measure sustained attention, an N-back task (NB3; 3-back) to assess working memory, a T vs. L visual search task (VS) to evaluate search accuracy and efficiency, and subjective sleepiness report (KSS) (Fig. 1A). Participants (n = 58) used the app multiple times throughout the day at their discretion (Fig. 1B). (Fig. S2: min = 13, max = 52, median = 23 entries per participant over an 8-day study period; Fig. S3: a representative study design for one participant). Across the 1428 subjective sleepiness reports, we captured the full range of subjective sleepiness, indicating that our methodology appropriately captured real-world variations in ‘tiredness’ throughout the day. The data exhibited minor positive skewness (0.4), with a minimum value of 1, a maximum value of 10, a mean of 4.5, and a standard deviation of 1.9.

Objective tasks of vigilance (n = 1334), working memory (n = 1341), and visual search (n = 1340) recorded correct hits, misses, false alarms, and reaction times for each attempt (ms). Using these records, a set of cognitive variables was extracted, including median reaction times of hits, accuracy, false negative/positive rates, difficulty slope of visual search, number of lapses in vigilance task (>500 ms), discriminability score (d’) of working memory and visual search, and inverse efficiency slopes (IES; mean reaction times per ratio of correct answers). The summary statistics of the cognitive measures were comparable to previous real-world cognitive task findings39 (Table S1). The average of the median reaction times for the vigilance task was 421.5 ms (min = 263.0 ms, max = 800 ms, SD = 79.3), with an average accuracy of 93.8% (SD = 9.4) and an average number of lapses of 6.1 (SD = 5.8). For the working memory task, the average of the median reaction times to correctly remember a letter within a 2 s window was 750.5 ms (min = 285.5 ms, max = 1755.0 ms, SD = 234.3 ms), with an average accuracy of 84.8% (SD = 12.6) and an average d’ of 2.0 (SD = 0.9). In the visual search task, the average of the median reaction times to correctly answer within a 10-s window was 2637.4 ms (min = 295.0 ms, max = 7523.5 ms, SD = 821.9 ms), with an average accuracy of 87.9% (SD = 9.6) and an average d’ of 2.7 (SD = 0.7).

Since each objective task had multiple outcome variables that were commonly correlated with each other (Pearson correlation up to 0.96), we performed dimension reduction using factor analysis (Table S2). This analysis resulted in two factors for vigilance (median reaction time and accuracy), three factors for working memory (median reaction time, false positive rate, and false negative rate), and three factors for visual search (inverse efficiency score, false positive rate, and false negative rate) (Fig. S4). The remaining analysis will therefore assess these variables.

Rhythm of cognitive performance in everyday life

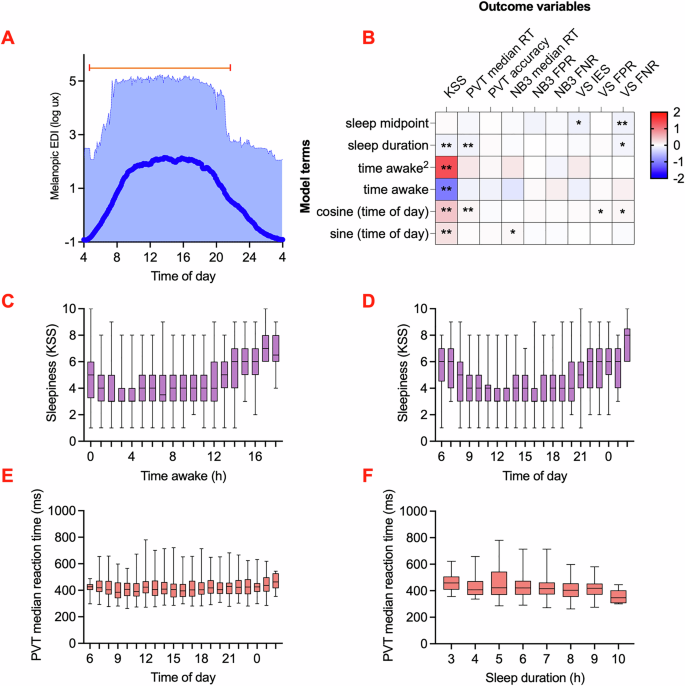

As expected, light exposure assessed with the wearable melanopic light logger (Spectrawear38) (Fig. 1A) exhibited time of day dependence. Across all 497 days of recording, global mean irradiance was 0.9 log lux melanopic equivalent daylight illumination (EDI) (SD = 1.5) (Fig. 2A). The maximum melanopic EDI per subject ranged from 4.4 to 5.2 log lux.

A Wrist-measured light exposure (mean and range log(melanopic EDI(lux))) across times of day for all observations collected by Spectrawear. The top line indicates daytime, with median sunset and sunrise times marked. B Results of the linear mixed model comparing sleep and diurnal rhythm variables to cognitive outcomes (KSS: n = 1405, PVT: n = 1312, NB3: n = 1323, VS: n = 1319). Time awake was modelled as a second-degree polynomial function, and time of day was represented as a harmonic fit line using cosine and sine terms. Scale bar indicates standardized coefficients of the linear mixed models. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.008. KSS Karolinska Sleepiness Scale; PVT Psychomotor Vigilance Task; NB3 3-Back Working Memory Test; VS Visual Search Task; RT reaction time; FPR false positive rate; FNR false negative rate. C Change in KSS over time awake. D Change in KSS over time of day. E Change in PVT median reaction time (ms) over time of day. F Change in PVT median reaction time (ms) over sleep duration. C–F The box extends from the 25th to the 75th percentile, with the median line inside, and the whiskers extending from the minimum to the maximum.

It is plausible that the cognitive variables we measured exhibit a diurnal rhythm, influenced by the natural circadian cycle. Furthermore, the timing and duration of recent sleep episodes, as well as the interval since the last waking, may significantly influence these cognitive outcomes. Therefore, we continued our analysis by investigating the rhythmic properties of cognitive function. The median time of day when cognitive tasks were performed was 16:06, with all clock times except 4–6 AM represented in our dataset. There was no statistically significant association between the median task completion time for each subject and the number of tasks completed during the week (r(56) = 0.08, 95% CI [–0.17, 0.33], p = 0.57), indicating that task timing preferences were not biased by the number of tasks completed. The mean time awake prior to task performance was 7.6 h (SD = 5.3). Additionally, the mean duration of the last sleep episode before each task was 7.1 h (SD = 1.2). The midpoint of the last sleep period occurred at an average time of 4:29 AM (SD = 1.4 h).

Subjective sleepiness scores showed strong associations with time of day, time awake, and the duration of the previous sleep episode (Fig. 2B). The subjective sleepiness model revealed that subjective sleepiness was typically higher within the first hour after wakening (mean=4.9) than later in the wake episode (mean daytime minimum = 3.7), indicative of sleep inertia, and then increased at approximately 0.4 subjective sleepiness points per hour later in the day (Time awake Std. Coef. = –1.04, 95% CI [–1.33, –0.75], p < 0.001, partial η² = 0.52; Time awake2 Std. Coef. = 1.36, 95% CI [1.07, 1.65], p < 0.001, partial η² = 0.64) (Fig. 2C). Given the strong relationship between sleep and clock time, it was not surprising to see a similar pattern for subjective sleepiness scores when plotted as a function of time of day, with a mean time of nadir in sleepiness at 14:21 (Sine (time of day) Std. Coef. = 0.24, 95% CI [0.17, 0.30], p < 0.001, partial η² = 0.48; Cosine (time of day) Std. Coef. = 0.44, 95% CI [0.36, 0.52], p < 0.001, partial η² = 0.67) (Fig. 2D). In comparison, the duration of the previous sleep episode had a relatively smaller effect on subjective sleepiness, with each additional hour of sleep reducing the daily mean subjective sleepiness score by 0.15 points (Std. Coef. = –0.10, 95% CI [–0.15, –0.04], p = 0.003, partial η² = 0.31).

Of the cognitive task parameters, median reaction time in the vigilance task showed statistically significant associations with the time of day and sleep duration, and the false negative ratio in the visual search task showed statistically significant associations with the sleep midpoint (Fig. 2B, Table S3). Thus, the amplitude of time-of-day variation was just 8 ms (Cosine (time of day) Std. Coef. = 0.07, 95% CI [0.02, 0.12], p = 0.005, partial η² = 0.14) (Fig. 2E). Each additional hour of sleep reduced the reaction time by 5 ms (Std. Coef. = –0.09, 95% CI [–0.13, –0.04], p < 0.001, partial η² = 0.08) (Fig. 2F). Visual search false negative rate decreased by 1% for each additional hour of later sleep midpoint time (Std. Coef. = –0.10, 95% CI [–0.17, –0.03], p = 0.006, partial η² = 0.007). Given that vigilance task reaction times are measured on a 100–1000 millisecond scale and visual search accuracy is assessed as a percentage, we acknowledge that, while statistically significant, these changes are relatively subtle in the context of within- and between-participant variability in these parameters.

Subjective sleepiness and cognitive performance were compared between weekdays and weekends. No statistically significant differences were observed for any variable except the visual search IES, which was lower on weekends by 150 ms (95% CI [46.1, 276.7], t(683.6) = 2.7, p = 0.006, Cohen’s d = 0.16). Daylength during the study ranged from 12.9 to 17.1 h. There was no statistically significant associations between daylength and subjective sleepiness (r(1403) = –0.01, 95% CI [–0.06, 0.04], p = 0.69) or vigilance task median reaction times (r(1310) = –0.03, 95% CI [–0.08, 0.03], p = 0.36), but small correlations (r < 0.20) were observed between daylength other cognitive measures. The direction of effect suggested that longer daylengths were associated with reduced cognitive speed and accuracy.

Cognitive performance is correlated with recent light exposure

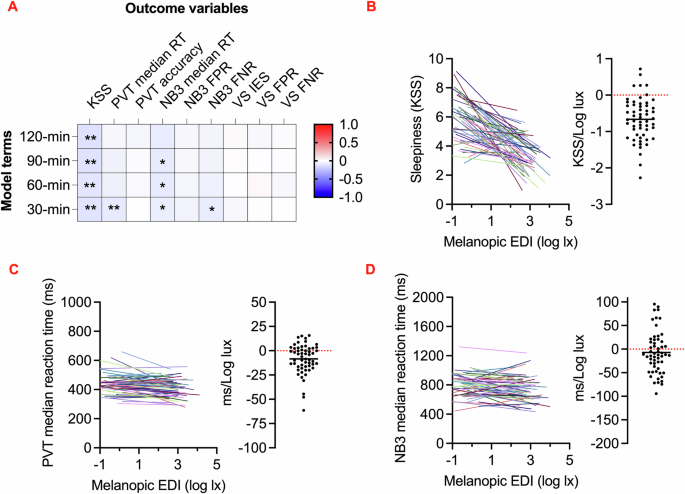

We next set out to ask whether cognitive task performance was correlated with recent light exposure. Including adjustments for time of day, time awake, last sleep duration, and last sleep midpoint, we assessed correlations with current light intensity as the mean light exposure over the preceding 30, 60, 90, and 120 min. This revealed correlations for subjective sleepiness, vigilance task and working memory reaction times, and working memory false negative rate. The effect was robust for the 30 min window for vigilance task reaction time and up to the 2 h window for subjective sleepiness, while working memory reaction time showed a moderate but consistent effect up to the 1.5 h window (Fig. 3A, Table S4).

A Heatmap shows standardized coefficients from linear mixed models comparing 30-, 60-, 90-, and 120 min light history with cognitive outcomes, including adjustments for time of day, time awake, last sleep duration, and last sleep midpoint. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.013. KSS Karolinska Sleepiness Scale; PVT Psychomotor Vigilance Task; NB3 3-Back Working Memory Test; VS Visual Search Task; RT reaction time; FPR false positive rate; FNR false negative rate. B–D Changes in cognitive performance with melanopic equivalent daylight illuminance (EDI, log lux) history (KSS: n = 1234, PVT: n = 1222, NB3: n = 1212). B Sleepiness (KSS) vs. 30-minute light history, C Psychomotor Vigilance Task (PVT) median reaction time (ms) vs. 30 min light history, and D 3-Back Working Memory Task (NB3) median reaction time (ms) vs. 30-minute light history. B–D The left plots illustrate linear regression lines for each individual. The right distribution plots display the mean and scatter of slopes derived from linear fits for each individual, with NB3 slopes adjusted for the learning effect.

Based on these findings, we utilized 30 min light history durations to model intensity-response relationships. By calculating the slopes of these curves, we quantified the relationship between light exposure and the three cognitive outcomes with most convincing light associations (subjective sleepiness, vigilance task reaction time, and working memory reaction time), offering an indication of cognitive sensitivity to light in real-world environments. On average, a 1 log-lux increase in melanopic EDI was associated with a 0.2-point reduction in subjective sleepiness as measured by the subjective sleepiness (Std. Coef. = –0.11, 95% CI [–0.18, –0.04], p = 0.003, partial η² = 0.14) (Fig. 3B). Despite this overall trend, substantial interindividual variability was observed (including six participants exhibiting positive slopes), indicating that the relationship between light and sleepiness varied among individuals. For the vigilance task, a 4 log-lux increase in melanopic EDI—from the sensor’s detection threshold to full sunlight — corresponded to an approximately 30 ms improvement in reaction time (Std. Coef. = –0.09, 95% CI [–0.14, –0.03], p = 0.003, partial η² = 0.09) (Fig. 3C). Similarly, but with a small effect size, working memory reaction time for correct short-term memory recall improved by roughly 60 ms across the same range of melanopic EDI (Std. Coef. = –0.07, 95% CI [–0.13, –0.01], p = 0.033, partial η² = 0.01; with task day adjusted for the learning effect) (Fig. 3D). Interestingly, interindividual variability appeared more pronounced for vigilance and working memory performance compared to subjective sleepiness scores, with nearly twice as many participants exhibiting positive slopes in these cognitive tasks. Coefficients of variation were calculated as −88.4 for subjective sleepiness, -181.1 for vigilance, and −633.1 for working memory, highlighting the diversity in correlation with light exposure across different cognitive measures.

Determinants of light and cognition correlation

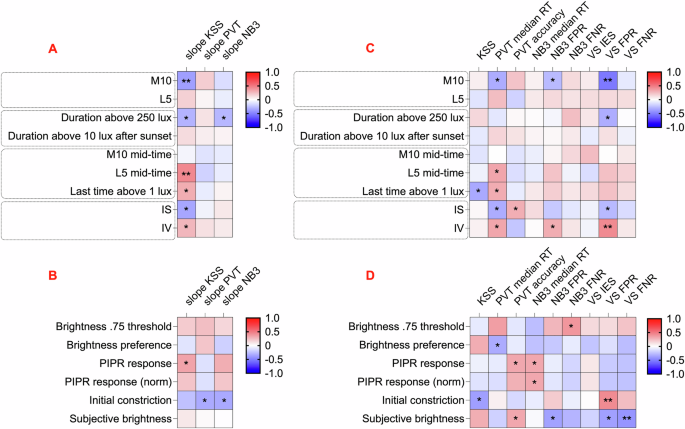

Having assessed within individual relationships between light exposure and performance, we moved to exploring the origins of inter-individual variation in the nature of this association. We first asked whether participants’ patterns of light exposure across the week were predictive of their sensitivity. To this end, we extracted various dimensions of light history known to affect circadian rhythms, including daytime and nighttime light intensity, duration of exposure, and the timing and stability of light exposure (see “Methods” for details). These habitual light exposure variables were subsequently compared to the slopes of the relationship between light and cognitive outcomes that demonstrated associations with light history, including subjective sleepiness, vigilance task reaction time, and working memory reaction time (Table S5). Higher M10, earlier clock times for the dimmest 5 h epoch and light exposure patterns with lower intra-daily variability and higher inter-daily stability all correlated with stronger associations between recent light exposure and subjective sleepiness. The strongest correlations were observed in the relationship between light and subjective sleepiness and timing of the main epoch of darkness (indicative of time in bed) (Fig. 4A). Specifically, participants whose dark epoch occurred later and had lower daytime light exposure showed less steep negative slopes for subjective sleepiness, indicating a weaker association between light and subjective sleepiness (L5 mid-time: r(52) = 0.44, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.20, 0.64] and M10: r(52) = –0.38, p = 0.005, 95% CI [–0.59, –0.12]; Figure S5A). These correlations remained robust after adjusting for age, sex, caffeine consumption, alcohol consumption, smoking, chronotype (MSFsc), and sleep problems (PSQI) (b = 0.22, SE = 0.08, 95% CI [0.05, 0.38], p = 0.013 and b = –0.76, SE = 0.29, 95% CI [–1.35, –0.17], p = 0.013 respectively).

The comparison of weekly light exposure variables (A, C) and in-lab photosensitivity measures (B, D) with real-world photosensitivity of cognitive measures (A, B) and weekly cognitive outputs (C, D) is presented. In (A–D), heatmaps show Pearson correlation coefficients, with *p < 0.05 and (A, C) **p < 0.006, (B, D) **p < 0.008. Sample sizes: A KSS: n = 54, PVT: n = 55, NB3: n = 54; B KSS: n = 39, PVT: n = 40, NB3: n = 39; C n = 56 for all models; D n = 41 for all models. KSS Karolinska Sleepiness Scale; PVT Psychomotor Vigilance Task; NB3 3-Back Working Memory Test; VS Visual Search Task; RT reaction time; FPR false positive rate; FNR false negative rate. Lower slope values indicate higher light sensitivity of KSS, PVT, or NB3, reflecting greater photosensitivity. In (A, C), light exposure predictors include intensity variables such as M10 (mean of the brightest 10 h period) and L5 (mean of the dimmest 5-hour period); duration variables such as the time spent above 250 Melanopic EDI lux (minutes) and the time spent above 10 Melanopic EDI lux after sunset (minutes); timing variables including the midpoint time of the M10 period, the midpoint time of the L5 period, and the last time above 1 Melanopic EDI lux; and stability variables such as IS (interdaily stability of light exposure) and IV (intradaily variability of light exposure). In (B, D), photosensitivity predictors include subjective brightness ratings (0–100), initial pupil constriction (%) in the post-illumination pupil response (PIPR) test, PIPR response (area under the curve between blue and red stimuli up to 6 s after the stimulus), PIPR response normalized to initial constriction, brightness preference (proportion of melanopsin-high choices at the highest melanopsin contrast), and brightness 0.75 threshold (the contrast at which melanopsin-high was chosen 75% of the time).

We next explored whether it was possible to predict cognitive task photosensitivity using in-lab assessments of light sensitivity. To this end, a subgroup of participants (n = 41) volunteered for in-lab assessments designed to measure melanopsin sensitivity through a series of pupillometric and perceptual psychophysics tasks43. The lab-based tests included the Post-Illumination Pupil Response (PIPR) test, silent substitution melanopic brightness discrimination tasks, and a subjective brightness assessment. The derived variables from these tasks were then analysed in relation to the real-world light sensitivity of cognitive functions mentioned earlier (Table S6). This failed to reveal strong associations (Fig. 4B).

Determinants of inter-individual differences in cognitive performance

We next asked whether any aspects of an individual’s light exposure profile correlated with overall cognitive performance (Table S7). Once again, we used nine cognitive performance measures (subjective sleepiness, vigilance task, working memory, and visual search), which were averaged across the week. The most consistent associations across endpoints were with the M10 (intensity over the day’s brightest 10 h) and IV (intra-daily variability) (Fig. 4C). Specifically, people with brighter daytime exposure (M10; Fig. S5B) and less fragmented daily patterns of light exposure (IV) had lower visual search false positive rate (r(54) = –0.53, p < 0.001, 95% CI [–0.69, –0.31] and r(54) = 0.44, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.20, 0.63] respectively) and lower working memory false positive rate (r(54) = –0.27, p = 0.043, 95% CI [–0.50, –0.01] and r(54) = 0.31, p = 0.021, 95% CI [0.05, 0.53] respectively), and reduced vigilance task reaction time (r(54) = –0.32, p = 0.015, 95% CI [–0.54, –0.07] and r(54) = 0.33, p = 0.013, 95% CI [0.08, 0.55] respectively). Correlations of visual search false positive rate with M10 and IV remained robust after adjusting for covariates (b = –14.4, SE = 3.30, 95% CI [–21.0, –7.7], p < 0.001 and b = 37.7, SE = 12.7, 95% CI 12.1, 63.4], p = 0.005 respectively).

Lastly, in-lab light sensitivity measures were compared to cognitive variables (Table S8). Initial pupil constriction had the most significant associations, with greater constriction indicative of greater false positives in visual search (r(39) = 0.43, p = 0.005, 95% CI [0.15, 0.65]; Fig. 4D). In addition, a higher rating of subjective brightness for a standard test stimulus was correlated with fewer false negatives in visual search (r(39) = –0.42, p = 0.007, 95% CI [–0.64, –0.12]; Fig. S5C). These associations remained robust after adjusting for demographic and lifestyle covariates (b = 0.70, SE = 0.19, 95% CI [0.32, 1.09], p = 0.001 and b = –0.24, SE = 0.10, 95% CI [–0.44, –0.04], p = 0.021 respectively).

<a href