Victoria GillScience correspondent, BBC News

Victoria Gill/BBC News

Victoria Gill/BBC NewsIf like me you have a spoiled, lazy dog who enjoys cheese-flavored treats, the fact that your pet’s ancestors were wild hunters may seem unfathomable.

But a major new study shows that their physical transformation from wolf to sofa-hogging furball began in the Middle Stone Age, much earlier than we previously thought.

“When you look at the Chihuahua – this is a wolf that has been living with humans for so long that it has adapted,” says the study’s lead researcher, Dr. Elowyn Evin of the University of Montpellier.

He and his colleagues found that the transformation of our domesticated animals, championed by the Victorians, through selective breeding actually began more than 10,000 years ago.

C Amin

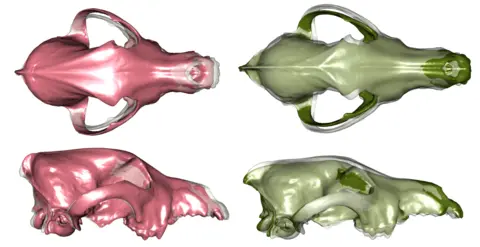

C AminIn a paper published in the journal Science, this international team of researchers focused their attention on prehistoric dog skulls. Over more than a decade, they collected, examined and scanned bones spanning 50,000 years of dog evolution.

They created digital 3D models of each of the more than 600 skulls examined – and compared the distinctive features of ancient and modern dogs – and their wild relatives.

This revealed that, around 11,000 years ago, just after the last Ice Age, the shape of dogs’ skulls began to change. While there were still lean, wolf-like dogs, there were also many with short snouts and broad, stocky heads.

Another lead researcher on the project, Dr Carly Amin of the University of Exeter, told BBC News that about half of the diversity we see in modern dog breeds today was already present in dog populations by the middle of the Stone Age.

“It’s really amazing,” she said. “And it begins to challenge ideas about whether it was the Victorians – and their kennel clubs – that drove it or not.”

C Brassard (VetAgro Super/Mechadev)

C Brassard (VetAgro Super/Mechadev)Domestication: An Ancient Mystery

Dogs were the first animals to be domesticated. There is evidence that humans have lived closely with dogs for at least 30,000 years. Where and why this close relationship began remains a mystery.

This study has revealed some of the earliest physical evidence of dogs transforming into the diverse range of pets, companions and working animals we know today. And digital scans of the skulls the researchers studied will help answer more questions about the evolutionary driving forces behind domestication.

Some researchers have suggested that humans and wolves came together almost accidentally, when wolves moved to the outskirts of hunter-gatherer communities in search of food.

Taming wolves would yield more food, and humans gradually came to rely on wolves to clean up dirty carcasses and sound the alarm if a hunter approached.

On why this changed the physical structure of the dogs, Dr. Amin said that there are likely to be many reasons for this. He didn’t dismiss our ancestors’ preference for boxy heads and beautiful, thin noses, but he explained: “It’s likely to be a combination of interactions with humans, adaptation to different environments, adaptation to different types of food – all of which are contributing to the explosion of diversity that we see.”

“It is difficult to sort out which of these may be most important.”

For thousands of years, our human story and the story of our dogs have been entangled. In another paper in the same edition of the journal Science, a research group led by scientists in China studied the ancient DNA of dogs that lived in Siberia, the central Eurasian steppe and northwest China between 9,700 and 870 years ago.

They concluded that the movement of domestic dogs in that area often coincided with the migration of people – hunters, farmers and herders. That’s why our dogs have been traveling with us – and integrated into our societies – for thousands of years.

I can’t say that my own stubborn, disobedient terrier offers me the advantage that previously domesticated wolves offered our ancestors. But I can see why, as research shows, once a dog came to get some leftover food, he wasn’t going back.