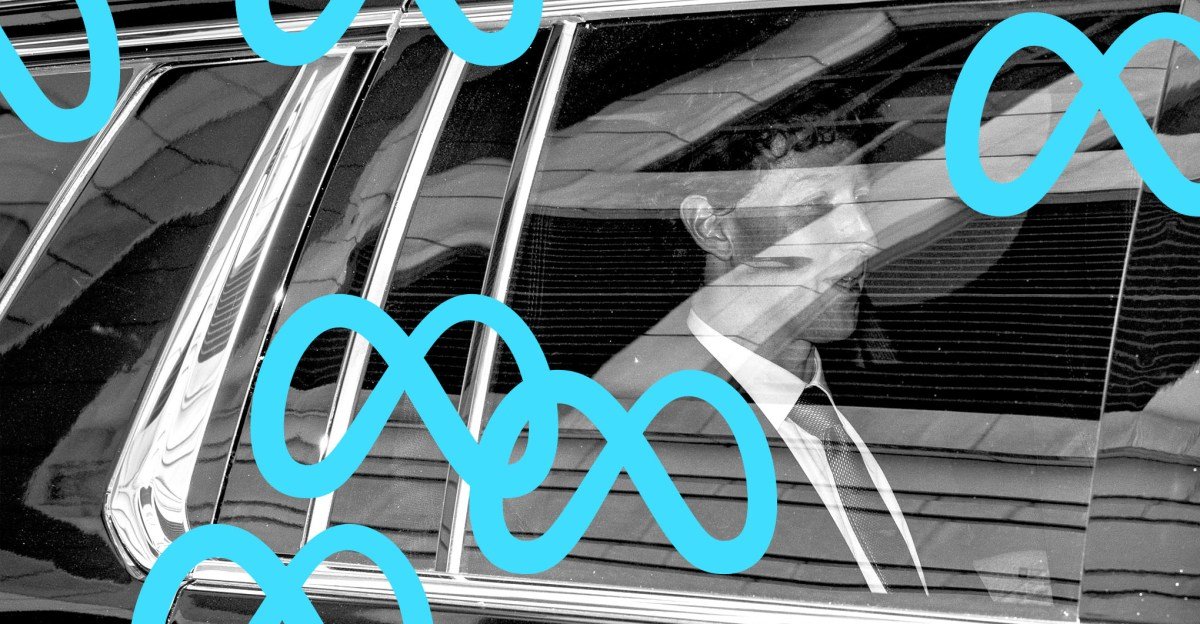

Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg entered the downtown Los Angeles courthouse the same way as all the lawyers, journalists and advocates who had come to watch testimony in his landmark trial, but with one notable difference: He was accompanied by a group that appeared to be wearing Meta’s Ray-Ban smart glasses. On his way to the courtroom, he walked past a crowd of parents whose children died after struggling with issues they blame on the design of the social media platform created by Meta. He spent the next eight hours often answering questions in his signature matter-of-fact (or less charitable, monotonous) cadence, denying that his platform was liable for the loss.

Zuckerberg was questioned in the morning session by lead plaintiff Mark Lanier of KGM. She is a 20-year-old woman who claims that Meta and Google’s design features encouraged her to compulsively use their apps and caused mental health problems, which the companies generally deny. Lanier’s charismatic style, inspired by his other profession as a pastor, was a sharp contrast to Zuckerberg’s reactions on the witness stand, where he tried to add nuance to discussions — and sometimes criticism — of various security decisions by employees. At times, Zuckerberg pushed back against Lanier’s characterization of his testimony. “I’m not saying that at all,” he said at one point. npr. Meanwhile, the judge advised people in the courtroom not to wear Meta’s AI glasses, and that they could be held in contempt of court if they fail to delete any recordings; Parents whose children died after experiencing loss are seen on his platform.

During his time on the stand, Zuckerberg was pressed on both his decisions at Meta and previous public statements. He was asked about perceived contradictions between earlier claims that he had tried to keep children under 13 off Facebook and Instagram and documents that described the importance of getting users on these platforms at an early age. He was also asked about decisions that would impact young users of his platform, such as his decision to lift the permanent ban on AR filters that alter users’ faces in ways that simulate cosmetic surgery.

“You don’t really make social media apps unless you care about people being able to express themselves”

Zuckerberg’s answer to the AR filter question helped clarify one of his strategies: arguing that Meta had made careful decisions to balance free expression against potential harm. During the testimony, Zuckerberg addressed a discussion among Meta executives in 2019 about whether to lift a temporary ban on the filter, which Instagram chief Adam Mosseri was asked about last week. Zuckerberg testified that after reviewing research on the impact of filters on user well-being, he felt that the available evidence of their harm was not sufficient to justify an agreement to limit one form of speech on the platform. “At some level you don’t really make a social media app unless you care about people being able to express themselves,” Zuckerberg said. “I think we need to be careful when we say, ‘There are restrictions on what people can say or express themselves.’ “I think we need to have clear evidence that things are going to be bad.”

Zuckerberg ultimately decided to allow creators to create some filters, except for things like copying nip and tuck lines, but did not recommend them or allow Instagram to create them itself.

Lanier suggested that Meta prioritized increasing users’ time on the platform rather than well-being, but – as he has long done in other settings – Zuckerberg insisted that Meta deliberately shifted its internal messaging to focus on increasing product value for users, even if it led to a short-term decline in usage. While some documents revealed that staff considered how banning filters might discourage some users, Zuckerberg said it was not a big factor in his decision because they were not extremely popular tools in the first place.

“I don’t have a college degree in anything.”

Still, Zuckerberg acknowledged that not everyone on his team agreed with the decision. “You have a group of people who care about well-being issues, who had some concern that there might be an issue, but they weren’t able to show any data that would compel me that there was enough of an issue to warrant restricting people’s expression,” he said. Lanier showed them an email from another Meta executive, who said she respected Zuckerberg’s call, but did not agree with it based on the risks and her personal experience with her daughter, who experienced body dysmorphia. “There will be no solid data to prove causal harm for many years,” the executive said.

When Zuckerberg reiterated that he did not find the available research sufficient to justify a blanket ban, Lanier asked if Zuckerberg had degrees in different professions. Zuckerberg responded, “I don’t have a college degree in anything.”

Zuckerberg’s all-day testimony concluded part of the second week of the trial, which was expected to last at least six. Jurors will soon hear from former Meta employees, including those who disagreed with the company’s approach to teen safety, and executives from YouTube, which is also a defendant in the case.

Parents watching from public seats told reporters they did not feel they learned anything new from the testimony, but several said they still felt it was important to make their presence felt in front of the CEO. “I think it’s very clear who the parents in the room are, and I hope that when he looks in that courtroom, as we’re sitting right there, that he sees that and that he feels that way, because we can only really get change from him if he’s empathetic,” said Amy Neville, whose son Alexander died at age 14 from fentanyl poisoning, which was allegedly facilitated by Snapchat (which had its own version of the KGM case. Part was solved). “When we can tap into their empathy, we can get the change that we want. And so hopefully, maybe we got a little bit of that today. It remains to be seen.”

<a href