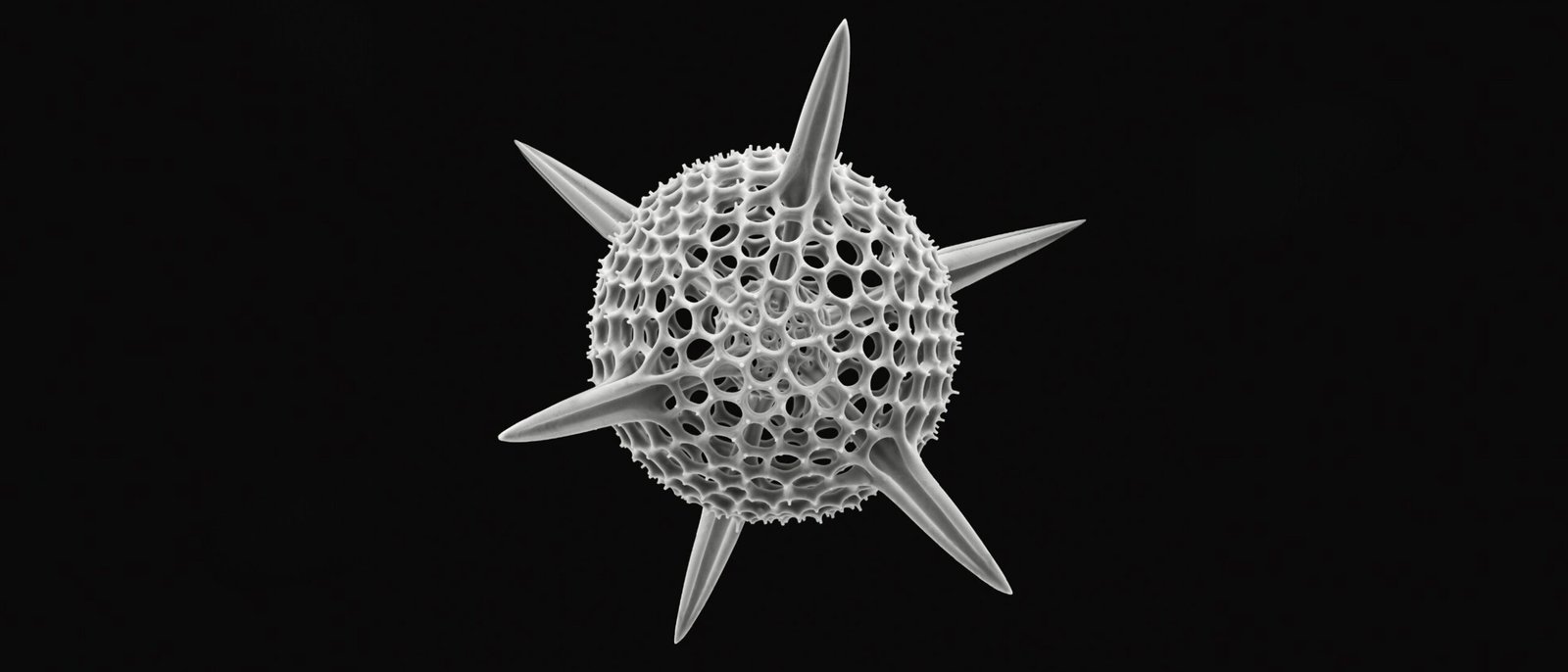

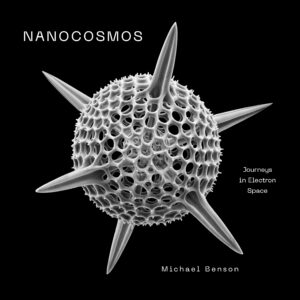

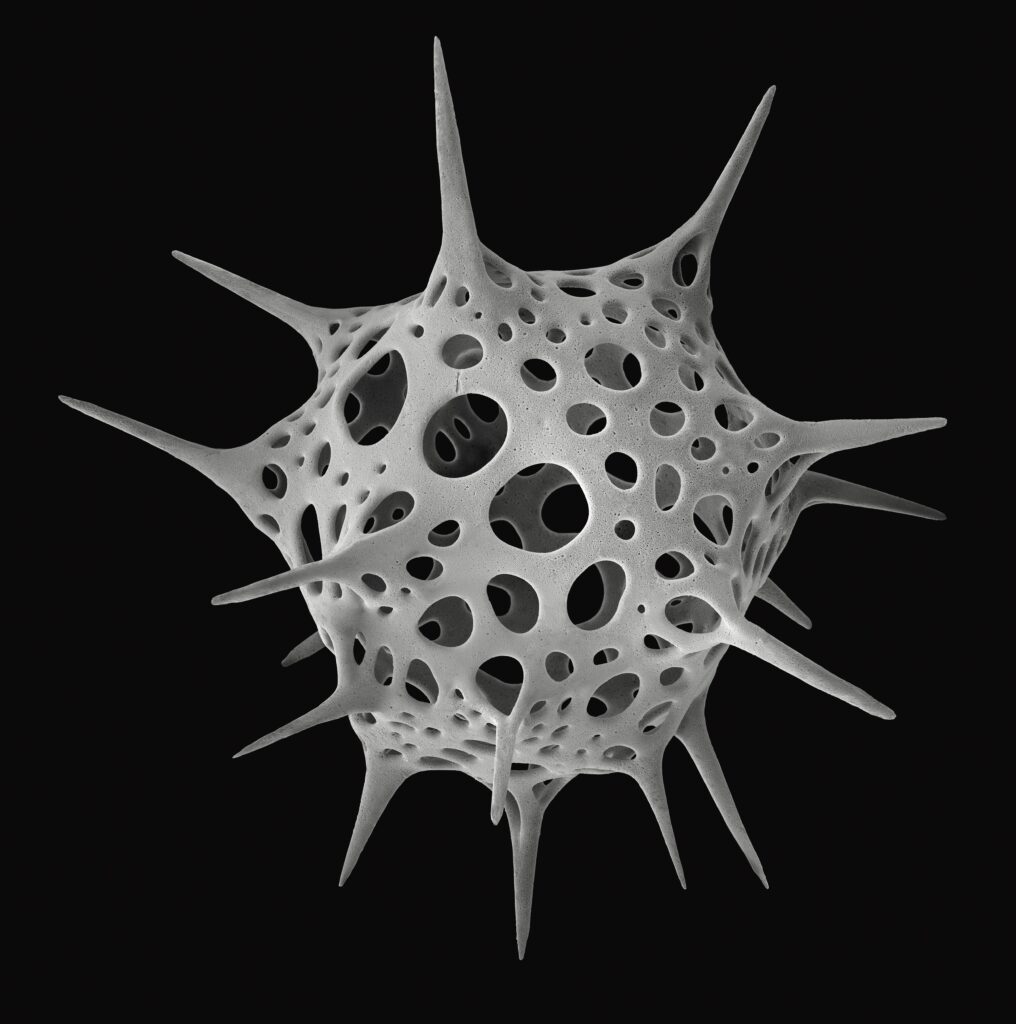

No creature of the microscopic world has succeeded in capturing the human imagination with such authority as the radiolarian. Since the late nineteenth century, they have made their presence felt in art, architecture, design and even literature. These single-celled sea creatures, which appear to have been teleported straight from some rare Euclidean space to all the world’s oceans, seamlessly combine geometry and biology. Their surprisingly complex glassine skeletons may serve to protect and regulate buoyancy for the cell inside, but they also appear to be a kind of physical embodiment in sculptural glass of what luminosity means.

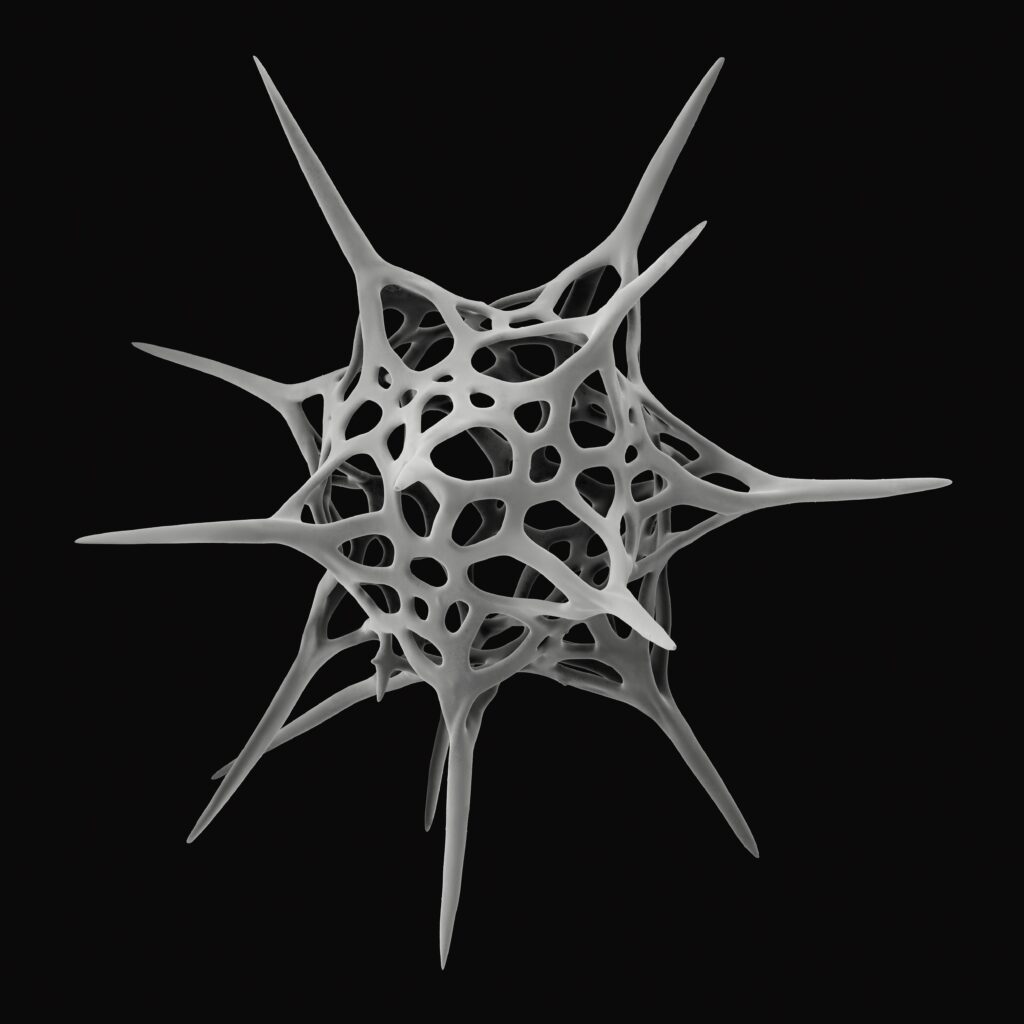

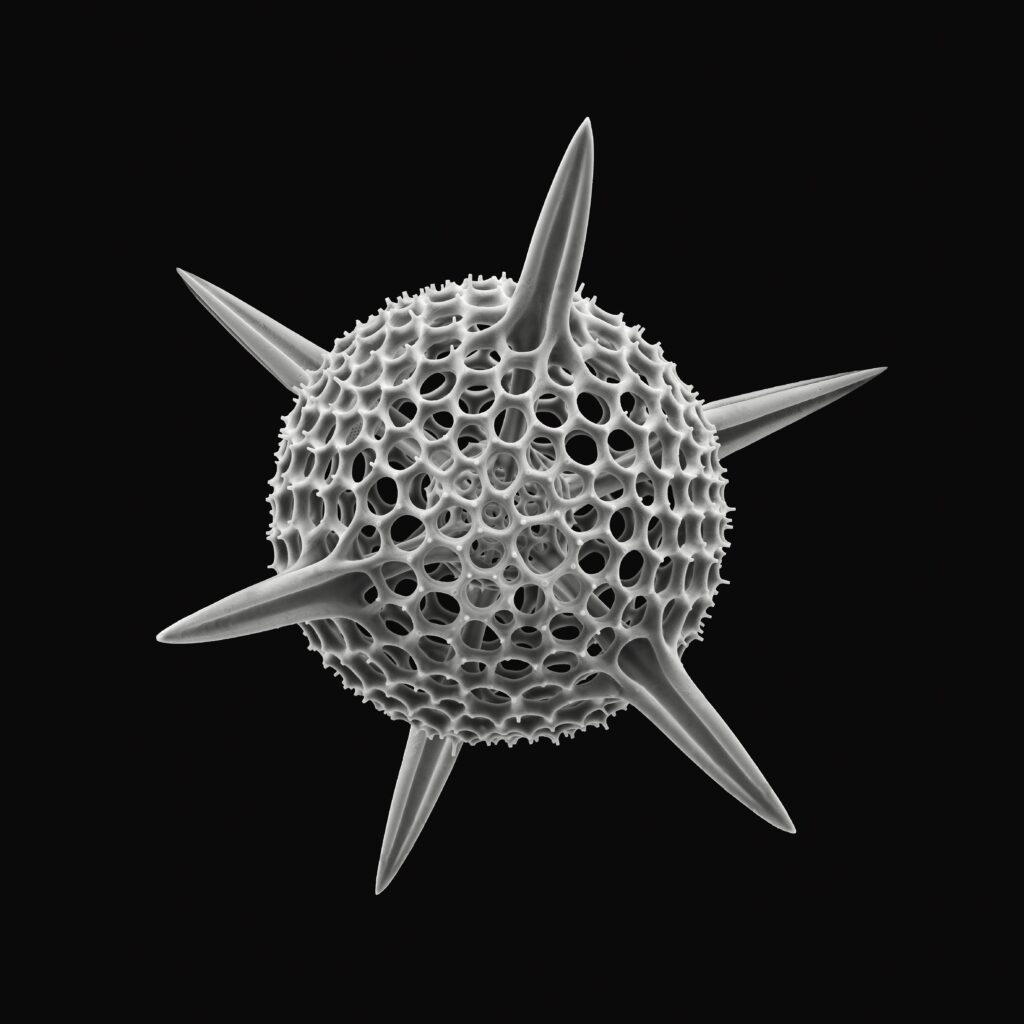

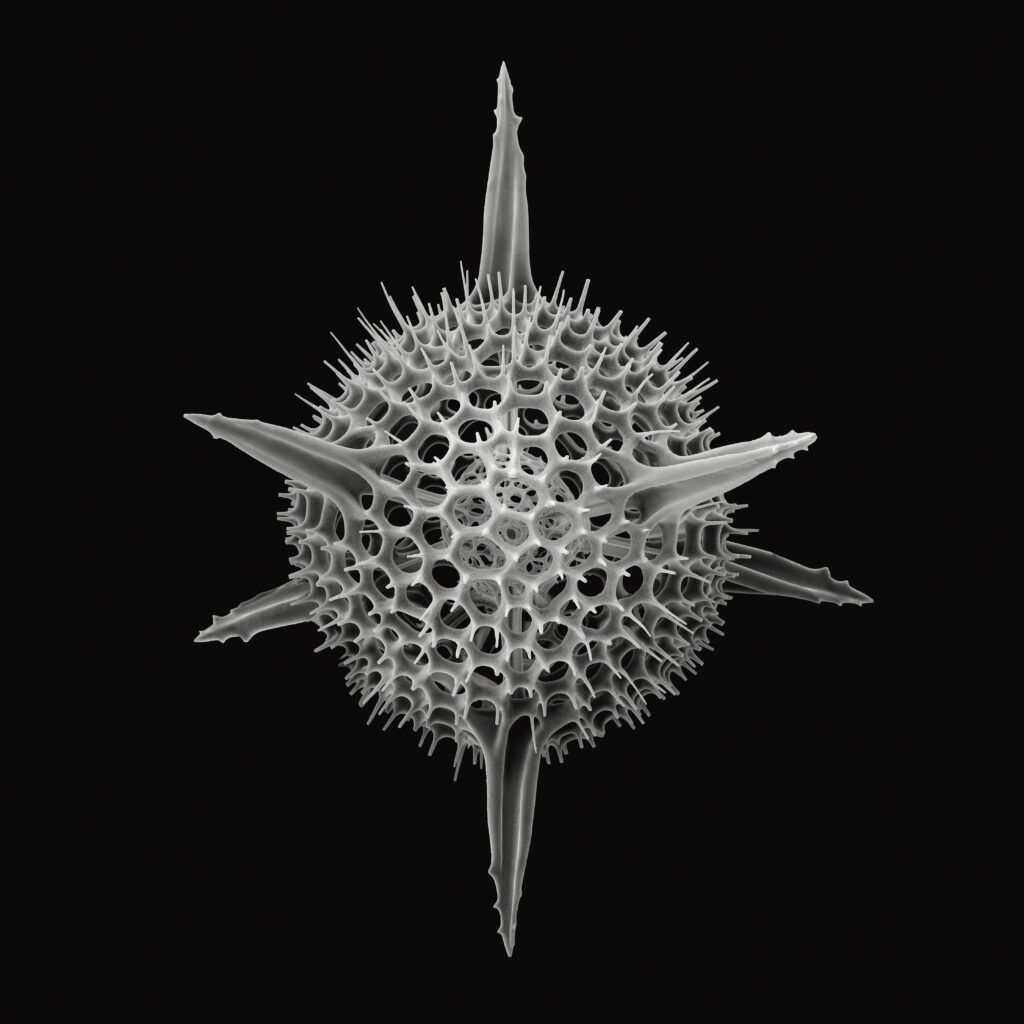

Radiolarians specialize in distilling silica, a form of quartz, from seawater, a process known as biomineralization. In the process, they generate a kind of frenetic geometer vocabulary of forms – polyhedra, Archimedean solids, icosahedrons, dodecahedrons and so on – tongue-curved shapes punctuated by spines and microtubule radiation. Their extraordinary shapes serve to refute any suggestion that organic forms should simplify as they become smaller.

1833 120 microns wide, 0.12 of a millimeter. © 2025 Michael Benson.

If anything, the opposite appears to be true. They can be found where salt water forms waves, but especially in the warm surface layers of the Indian and Pacific oceans. No one species is dominant.

The complexity packed within the geometry is a Radiolarian signature.

Radiolarian skeletons are typically constructed from an arranged mesh of rigid polygons. These are often shaped into nested spheres – although there are many exceptions, including complex axial symmetry. The central region contains the endoplasm and nucleus of the cell, which is the site of greatest cellular activity. Surrounding it and protected by an outer shell is the cytoplasm, which is a foamy liquid containing protein-synthesizing ribosomes, energy-producing mitochondria, energy-storing lipids, and so on.

Most radiolarians are heterotrophic, meaning they consume plant and animal matter, but many also have photosynthetic capabilities due to endosymbiosis (in which one organism, the photosynthetic, lives within the larger radiolarian for the benefit of both). This allows them to obtain energy from sunlight as well. Their distinctive projecting spines act as flotation modulators (through a complex process such as raising and lowering the protoplasmic sail) and mast form to allow the cell to extend itself outward into the surrounding water and feed. The complexity packed within the geometry is a Radiolarian signature.

Despite all this, they only live for about two weeks. After which the radiolarians sink, causing a continuous snowfall of the delicate glasswork on the ocean floor. Depending on the depth, it could take up to fifty years for their skeletons to sink to the bottom – there has been consistent light rain in all of the world’s oceans since at least the mid-Cambrian era, 500 million years ago. The resulting carpet of fallen forms eventually mixes into a siliceous res which, on million-year time scales, eventually produces a particularly dense, fine-grained rock called radiolarite, aka chert or flint.

In this way, one of the first forms of life to possess any kind of skeleton returned to land. Chert was used by some early protohumans to make tools and thus was an important material in the 3.4 million year long Stone Age. There are many ways to infiltrate human culture.

So how did radiolarians manage to do anything more than this in relatively recent history? There is a story in this.

In 1859, a young German physician newly licensed to practice surgery and obstetrics decided to take a trip to Italy. Ernst Haeckel was never completely convinced that medicine was his vocation. He went into the field under parental pressure and was dismayed by the surgical gimmickry of medical school.

1433 Approximately 150 microns, 0.15 millimeters © 2025 Michael Benson

But Haeckel’s side was certainly research-oriented and his interest in the natural sciences was supported by the anatomist Albert von Kölliker, a distinguished professor at the University of Wurzburg. Deploying the latest compound microscopes being manufactured by Carl Zeiss in nearby Jena, von Kölliker virtually moved from the dissection table to the laboratory, thereby establishing a new medical field: microscopic anatomy.

Amazed by their radial symmetry and gem-like skeletons, Haeckel felt that the only way to do justice to radiolarians was to depict them with as much accuracy as possible.

Haeckel’s Italian trip was part of a secret alternative life plan. While visiting a friend at the University of Jena, he was offered the possibility of an academic career – which he chose to keep confidential. The friend, Carl Gegenbauer, was already a professor at the university. He recommended Italy as an ideal educational destination for the young Ernst in preparation for a possible post at Jena.

At the beginning of his journey Haeckel was still shaken by the death, probably by suicide, of one of his professors, the distinguished physician and marine biologist Johannes Müller. He was determined to continue the research on Radiolaria, a type of marine organism, that Müller had begun.

Considered one of the greatest natural philosophers of the nineteenth century, Müller was among the first to describe this group of single-celled plankton with complex skeletal structures. He also coined the term radiolarion, which is derived from the Latin radiolusWhich refers to their specific radiation points. Working primarily in the North Sea, Müller pioneered the use of extremely fine nets to collect these and other small sea creatures.

On an extended visit to Messina, Haeckel planned to resume Müller’s radiolarian work. He employed an elderly fisherman in the Sicilian port city, Domenico Nina, while he was scouring the sea with nets based on Müller’s design. Investigating what he brought back with growing fascination, he quickly realized that the rich waters of the Strait of Messina – a unique Mediterranean environment where strong currents funnel nutrients through a narrow space – were giving rise to dozens of previously undiscovered species.

Just as the use of von Kölliker’s microscope in anatomy had created a new field, now the combination of Müller’s trap, Haeckel’s artistic abilities, and a special feature of the microscope brought from Germany, manufactured by the Berlin company Schieck, enabled a new chapter in marine biology – which he had the opportunity to write.

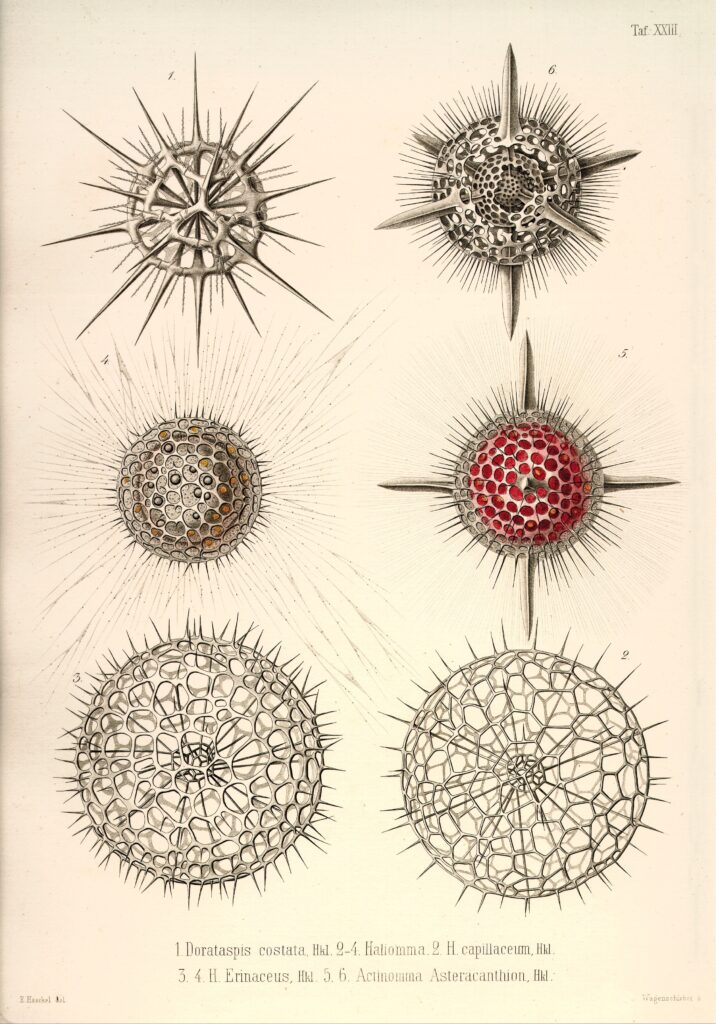

Amazed by their radial symmetry and gem-like skeletons, Haeckel felt that the only way to do justice to radiolarians was to depict them with as much accuracy as possible. To accomplish this, he used his microscope’s camera lucida attachment – an advanced feature that enabled him to project his marine specimens directly onto paper, where they could be traced by his pen. The results were unprecedentedly accurate renderings.

By the early 1860s, Haeckel had discovered over a hundred new radiolarian species. Clearly in using his artistic abilities for a creative scientific expedition, he also achieved his own merits. By 1862 he had published an illustrated monograph, radiolarionWhich he dedicated to Johannes Müller. It contained ten brilliantly colored plates, each of which depicted several species in detail.

ernst haeckel art forms in nature It remains one of the most influential illustrated books ever published.

Nothing like it had ever been seen before, and when Haeckel sent a copy to Charles Darwin, whose on the origin of Species Published only three years earlier, it soon received an enthusiastic response. The great naturalist wrote, “It is one of the most magnificent creations I have ever seen, and I am proud to possess a copy from the author.” “It is very interesting and instructive to study your admirably made pictures; for I did not know that animals with so little organization could develop such beautiful structures.”

Having established himself as a marine biologist and establishing relationships with the greatest scientists of his time, Haeckel rapidly gained international fame. Constantly illustrated monographs on marine sponges, jellyfish, and zoology earned him a full professorship at Jena, and he became the leading proponent of Darwin’s evolutionary theories in Germany.

By the end of the 1870s, he was asked to participate in the huge task of evaluating and cataloging the results of five years. contender The expedition – an ambitious British global research voyage, dedicated purely to science for the first time. Haeckel’s contribution to the final 50-volume Voyage Report of HMS Challenger It took a decade to complete and consisted of three volumes, 2,750 pages and 130 plates.

The latter was produced with the talented master lithographer Adolf Giltsch, a lifelong colleague from Jena who had “the enlightenment-seeking inspiration of a true naturalist”, as Haeckel put it. in his contender Working alone, Haeckel described over 4,000 new radiolarian species. He had by now become the leading authority on the subject.

Ernst Haeckel and Adolf Giltsch, Radiolarians, 1887, lithograph.

Smithsonian Libraries and Archives.

By the end of the century, Ernst Haeckel had collected enough drawings to create his magnum opus and the single most famous work bearing his name, Kunstformen der Nature ,art forms in natureOnce again, Giltsch’s lithographs transformed Haeckel’s drawings into finely rendered renditions suitable for large-scale reproduction. Radiolarians were visible throughout the book, which was published as separate volumes between 1899 and 1904 and eventually as a complete edition in 1904 with one hundred full-page lithographs. It was an immediate commercial success; it never went out of print.

As already mentioned in the introduction, art forms in nature Had an almost immediate impact on the visual culture of the early twentieth century. Artists of the Art Nouveau and German Jugendstil movements incorporated Haeckel’s discoveries into their work, as did prominent architects and designers such as Antoni Gaudí and Louis Sullivan. In 1898, architect René Binet unveiled his design for the Porte Monumentale, a grand three-legged archway intended to serve as the entrance to the upcoming 1900 Paris Exposition. The massive structure was based on the radiolarian that Binet had seen at Haeckel. contender Plates, a fact he made clear in letters to the marine biologist, now in his late sixties.

The Port of Binet was duly constructed late the following year and marks a kind of apotheosis of naturalistic design incorporated within architecture. Comparable in size to the Arc de Triomphe, the Porte Monumentale also featured surface ornamentation based on Haeckel’s precise lifetime documentation of organisms found in the world’s oceans. However, when the exhibition closed that November, it was unceremoniously taken away, never to be seen again.

In contrast, Ernst Haeckel’s art forms in nature It remains one of the most influential illustrated books ever published. Ranking as the first international image-based art-science bestseller, it brought to the public the enduring mystery of nature’s extraordinary ability to create dazzlingly complex structures.

,

From Nanocosmos: Electron Journeys into SpaceUsed with permission of the publisher, Abrams Books, Copyright © 2025 by Michael Benson