BBC

BBCIn the bright lights of an operating theater in the Indian capital Delhi, a woman lies unconscious as surgeons prepare to remove her gallbladder.

She is under general anesthesia: unconscious, insensitive, and completely immobilized by a mixture of drugs that induce deep sleep, block memory, blunt pain, and temporarily paralyze her muscles.

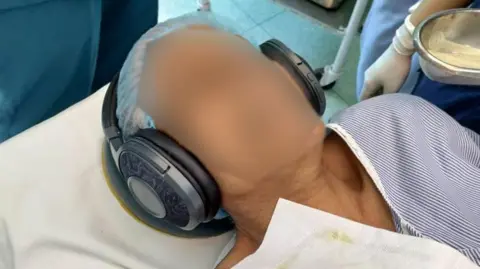

Yet, amidst the hum of the monitors and the steady rhythm of the surgical team, a light stream of flute music plays through the headphones placed over her ears.

Even though the medications silence most of his brain, his auditory pathways remain partially active. When she wakes up, she will regain consciousness more quickly and clearly because she will require lower doses of anesthetic drugs such as propofol and opioid painkillers compared to patients who did not listen to music.

At least, that’s what a new peer-reviewed study from Delhi’s Maulana Azad Medical College and Lok Nayak Hospital suggests. The research, published in the journal Music & Medicine, offers some of the strongest evidence to date that music played during general anesthesia can modestly but meaningfully reduce medication requirements and improve recovery.

The study focused on patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy, the standard keyhole operation to remove the gallbladder. The procedure is short – usually less than an hour – and typically demands fast, “clear-led” recovery.

To understand why researchers turned to music, it helps to understand the modern practice of anesthesia.

“Our objective is early discharge after surgery,” says Dr. Farah Hussain, a senior expert in anesthesia and a certified music therapist for the study. “Patients need to wake up clear-minded, alert and oriented, and ideally pain-free. With better pain management, the stress response is reduced.”

Achieving this requires a carefully balanced mixture of five or six drugs that work together to put the patient to sleep, block pain, block the memory of the surgery, and relax the muscles.

getty images

getty imagesIn procedures such as laparoscopic gall bladder removal, anesthesiologists now often supplement this drug regimen with regional “blocks” – ultrasound-guided injections that numb the nerves in the abdominal wall.

“General anesthesia plus block is ideal,” says Dr. Tanvi Goyal, primary investigator and former senior resident at Maulana Azad Medical College. “We’ve been doing this for decades.”

But the body does not accept surgery easily. Even under anesthesia, it reacts: heart rate increases, hormones increase, blood pressure increases. Reducing and managing this cascade is one of the central goals of modern surgical care. Dr. Hussain explains that the stress response can slow recovery and increase inflammation, highlighting why careful management is so important.

The stress begins even before the first cut, with intubation – the insertion of a breathing tube into the windpipe.

To do this, the anesthesiologist uses a laryngoscope to elevate the tongue and soft tissues at the base of the throat, obtain a clear view of the vocal cords, and guide the tube into the trachea. This is a routine step in general anesthesia that keeps the airway open and allows precise control over the patient’s breathing while he or she is unconscious.

“Laryngoscopy and intubation are considered the most stressful responses during general anesthesia,” says Dr. Sonia Wadhawan, director-professor, anesthesia and intensive care at Maulana Azad Medical College and supervisor of the study.

“Although the patient is unconscious and will not remember anything, his body still reacts to the stress with changes in heart rate, blood pressure and stress hormones.”

Certainly, medicines have evolved. The old ethereal masks have disappeared. In their place are intravenous agents – notably propofol, the hypnotic substance that became infamous for causing the death of Michael Jackson but is appreciated in operating theaters for its rapid onset and clean recovery. “Propofol works within about 12 seconds,” says Dr. Goyal. “We prefer it for minor surgeries like laparoscopic cholecystectomy because it avoids the ‘hangover’ caused by inhaled gases.”

The team of researchers wanted to know if music could reduce patients’ need for propofol and fentanyl (an opioid painkiller). Less medications means faster awakening, stable vital signs and fewer side effects.

So he designed a study. A pilot involving eight patients ran a full 11-month trial on 56 adults, approximately 20 to 45 years of age, who were randomly divided into two groups. All were given the same five-drug regimen: a drug that prevents nausea and vomiting, a sedative, fentanyl, propofol, and a muscle relaxant. Both groups wore noise-canceling headphones – but only one heard music.

“We asked patients to choose between two quiet musical instruments – a soft flute or a piano,” says Dr. Hussain. “There are still areas in the unconscious mind that remain active. Even if the music is not explicitly remembered, implicit awareness can produce beneficial effects.”

The results were shocking.

Patients exposed to music require lower doses of propofol and fentanyl. They experienced better recovery, lower cortisol or stress-hormone levels and better control of blood pressure during surgery. “Since the ability to hear remains intact under anesthesia,” the researchers write, “music may still shape the internal state of the brain.”

Apparently, music seemed to calm the inner storm. “The auditory pathways are still active even when you’re unconscious,” says Dr. Wadhawan. “You may not remember the music, but the brain registers it.”

The idea that the mind behind the anesthetic veil is not completely silent has long troubled scientists. In rare cases of “intraoperative awareness” patients remember fragments of operating-room conversations.

If the brain is able to perceive and remember stressful experiences during surgery – even when a patient is unconscious – it may also be able to register positive or relaxing experiences such as music, even without conscious memory.

“We are only beginning to explore how the unconscious mind responds to non-pharmacological interventions such as music,” says Dr. Hussain. “It’s a way to humanize the operating room.”

Music therapy is not a new thing in the field of medicine; It has long been used in psychiatry, stroke rehabilitation and palliative care. But its entry into the highly technical, machine-ruled world of anesthesia marks a quiet change.

If such a simple intervention could reduce medication use and speed up recovery – even if modestly – it could reshape the way hospitals think about surgical wellness.

As the research team prepares its next study exploring music-based sedation based on earlier findings, one truth is already humming through the data: Even when the body is calm and the mind is asleep, it appears that a few gentle notes can help initiate the treatment.

<a href