The most interesting robots are not built to do work, but to make us imagine other worlds.

A few months ago, I visited the Futurism retrospective organized to commemorate the 80th anniversary of the death of Filippo Tommaso Marinetti at the National Gallery in Rome. The rooms were filled with archives of ultra-modernist mechanical dreams: engines, telegraphs, cars and airplanes as well as posters, paintings and sculptures. It was impossible to ignore the voice of Futurism’s visionary thinker echoing from the museum’s cool neoclassical halls: “We affirm that the grandeur of the world has been enriched by a new beauty: the beauty of motion.”

For the Futurists, every machine was, essentially, a time-machine: more than devices designed to perform a specific task, technological objects were the historical embodiment of humanity’s universal drive toward progress. Looking beyond the notoriously controversial implications of its political affiliations, the genius of the futurist avant-garde was its intuition that the development of machines could capture cultural changes better than any other human practice. And thus, art and writing – the highest expressions of humanism – also had to hear the rumble of engines.

In October 2021, visitors to London’s Tate Modern entered a space filled with visions of a very different future. Floating, semi-transparent creatures hovered softly in the air like seraphic creatures from the depths of the ocean. in aerobicsBecause they were baptized by the Korean-American artist Anika Yi, who imagined them, they are pachydermic, calm and silent. These flying automata react to human presence, changing altitude and behavior depending on the proximity of people in space. “When you look at these aerobes, it gives you almost the opposite feeling of the uncanny valley”, explains Yee. “You know they’re mechanical, yet they feel distinctly alive.” Unlike anthropomorphic robots, whose imperfect resemblance to humans often creates a sense of subtle unease (or “unnaturalness”), Yee’s automata are neither unsettling nor reassuring, but are designed to create a sense of sublime otherness, like swimming with whales in the ocean. Their scale is impressive, but their appearance attracts attention rather than fear. These artistic-technical objects are difficult to define: they are man-made artefacts but perform no instrumental function. They move around their environment, interacting with each other and the world around them, guided by their perceptions. Borrowing a term from Donna Haraway, Yee describes them as “a new kind of companion species.” In Haraway’s words, a “companion species” is not a familiar reflection of the human, but a meaningful otherness, whose distance from us enables us to live in new forms of relation and coexistence.

There is something paradigmatic and powerful about robots that dominate our imagination of the future.

Robots are strange objects of investigation. Whenever I encounter them in my research, I consider the difference between their negligible impact on my daily life and their dominant presence in my cultural imagination. Of course, industrial robots already serve important purposes, but their utility does not fully justify their appeal to us. Beyond its intended use, each robot, in its synthetic and self-sufficient individuality, represents something like the quintessence of a technological object. There is something iconic and powerful about these creatures that dominates our imagination of the future. And while the term “robot” has long corresponded to a very specific image (an anthropomorphic, mechanical, rigid artifact), Anika Yee’s flying automata signals a broader shift in the way these technological objects are imagined and constructed.

Over the past 20 years, there has been a significant change in robotics. The field once dominated by anthropomorphic bodies and rigid materials has begun to embrace a wide range of possible incarnations, starting with the use of plastics and flexible materials to replace steel and rigid polymers. Cecilia Laschi, one of the most authoritative figures in the field of robotics, has often emphasized how this change from “hard” to “soft” robots goes far beyond a simple change in the choice of materials, reflecting a broader change in the entire anatomy of the automata, in the strategies used to control them, and in the philosophy governing their construction. The most notable engineering achievement of Leschi and his colleagues at the Sant’Anna Institute of Pisa is a robotic arm originally designed in 2011 and inspired by the muscular hydrostatics of an octopus. In octopuses, limbs are capable of performing complex behaviors such as swimming and manipulating objects through coordinated contractions of muscle tissue, without the need for rigid components. In the robot designed by Laschi and his colleagues, robotic limb movement is achieved through deformable smart materials known as “shape memory alloys.”

Unlike a traditional robot, these movements are not pre-programmed, but rather emerge from the material’s response to external forces. This new engineering logic is part of the embodied intelligence described by Laschi, an approach in which a robot’s behavior emerges from integrating its physical structure and interactions with the world. The concept of “embodiment” challenges the hierarchical separation between body and mind, representation and experience. Rather than imagining intelligence as the product of an active mind controlling a passive body, embodiment emphasizes the connection between cognition and materiality. Originating in philosophy, over the past 20 years, this concept has begun to spread and establish itself in the field of engineering, opening new avenues for the design of versatile and adaptive robots. “The octopus is a biological demonstration of how closely effective behavior in the real world is linked to body morphology,” Laschi and her colleagues explain, “a good example of embodied intelligence, the principles of which are derived from the observation in nature that adaptive behavior emerges from complex and dynamic interactions between body morphology, sensorimotor control, and the environment.”

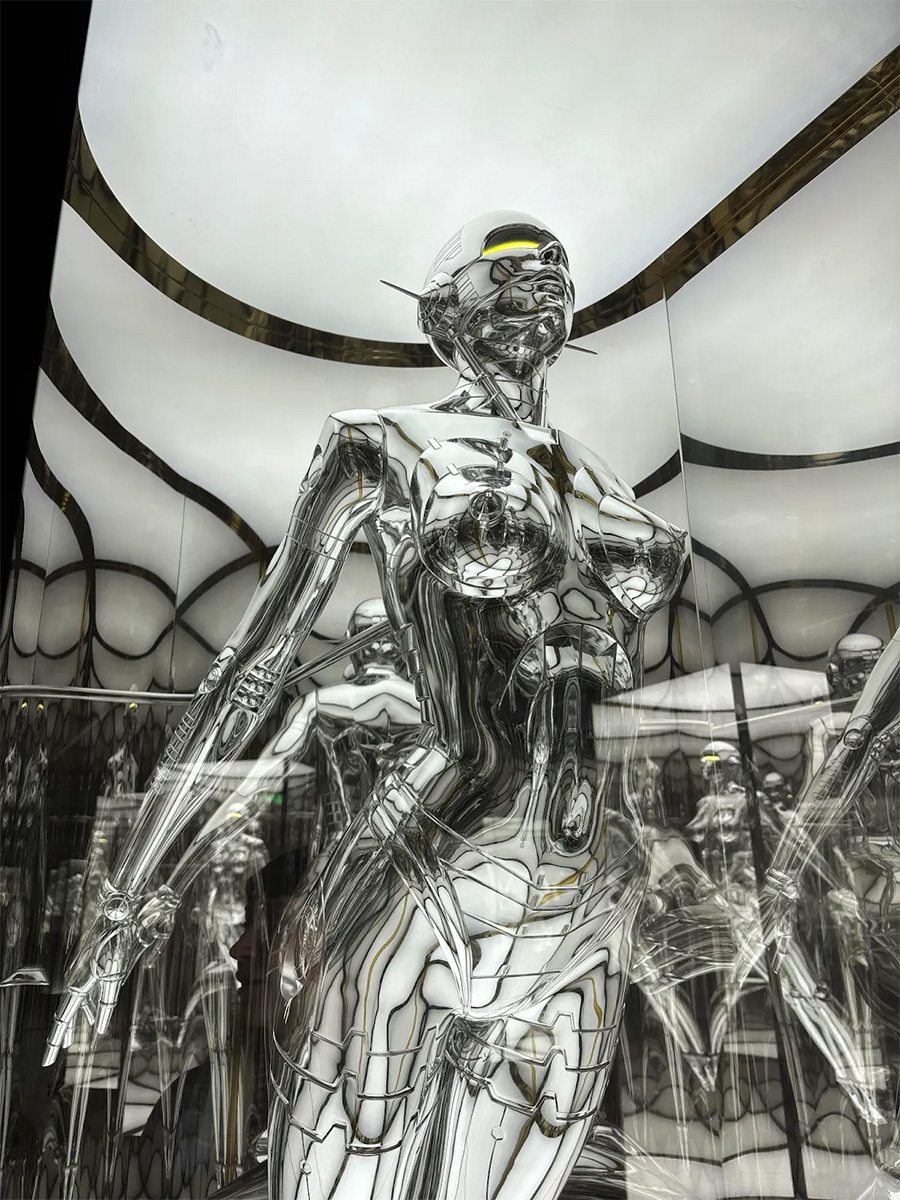

Back in Shanghai, shortly after visiting the National Gallery, I visited a retrospective on Hajime Sorayama, a Japanese artist famous for crystallizing the image of 20th-century robots into simultaneously futuristic and nostalgic icons. Since the 1980s, Sorayama has endlessly reproduced the same sculpture with minimal variations: a slim, shapely female figure covered in chrome-plated armor, halfway between an erotic fetish and a deity of a long-lost future. These creations, branded with the acronym “Sexy Robot” followed by a serial number, celebrate and mock the modernist stereotype of the automaton as a triumph of control and mechanical efficiency, mimicking the seductive mirage of shiny, endless progress. While Yi’s creatures introduce us to an alien and still nascent technological future, Sorayama’s figures are as captivating as they so perfectly reflect our expectations. if yi’s aerobics Soft, sentient, and fundamentally non-human, Sorayama’s sexy robots are superhuman, luminous, and surprisingly insensitive.

Despite their fundamental aesthetics and philosophical distance, Sorayama and Yi’s robots have at least one thing in common – their uselessness. More specifically, they are both tools for aesthetic contemplation rather than functional tools. For that matter, robots are often described in terms of what they can do: as artifacts designed to facilitate work, if not complete it for us. This concept, already described in the familiar etymology of the word “robot” (from Czech Robota“Forced labor,” a term popularized by science fiction author Karel Čapek), is deeply entrenched in twentieth-century industrial culture. Yet, even before being called by this name, robots were not always mere tools in the service of human productivity.

In a 1964 article titled Automata and mechanisms and the origins of mechanical philosophyHistorian of technology Derek de Sola Price traces the history of automata from ancient times, challenging the notion that such machines were created primarily to serve human labor. Mechanisms, he observed, functioned as epistemological devices long before they became useful tools: they functioned as microcosmic mirrors onto the larger order of the world. For centuries, automata have accompanied the human imagination, helping thinkers imagine a rational universe governed by regular mechanisms (before such mechanisms were put into practical use). This historical lineage complicates seeing the machine as a purely instrumental device: its material utility was often secondary to its epistemic power. This non-utilitarian interest in robots is emerging again and again in art practices.

Robots weren’t always mere tools in the service of human productivity.

In “After Care,” an installation recently exhibited at Copenhagen Contemporary, artists Rhoda Ting and Mikael Bojesen set up completely soft, pneumatically actuated robots to swing and sink inside a large pit of rocks and dirt. Visitors were invited to handle the robots as if they were in a “petting zoo” – engaging with them not as tools but as alien “companion species”, valued more for their strangeness and appearance than for any practical use.

The work of Cecilia Laschi and many other pioneers in robotics is already demonstrating that new soft robots can significantly expand the functionality, stability, and flexibility of technologies from past centuries. However, beyond the still limited applications of these artefacts, 21st century soft machines seem to signal a more complex transition, primarily epistemological and cultural, in our understanding of and relationships with the world.

Yi’s fluttering creatures and Ting and Bojesen’s swinging mollusks exist in continuity with a long history in which technological artifacts were philosophical and cosmological tools before they were tools programmed to perform a function. And if the automata of past centuries spoke of celestial spheres and universes arranged like clockwork, what worlds do the soft machines of the 21st century evoke? Even contemporary robots, whether floating in engineering laboratories or in art galleries, are first and foremost cosmological mirrors, and the world they evoke is very different from that of their ancestors. The new automata seem to speak to us of ecological continuity, profound otherness, and possible coexistence with what is furthest from us.

Laura Tripaldi is a writer and researcher at the Center for AI Culture at NYU Shanghai. She is the author of “Parallel Minds” (Urbanomic Press).

This article first appeared on Laura’s Substack, Soft Futures.