Most of the developer world is familiar with AWS outages us-east-1 This happened on October 20 due to a race condition bug inside the DNS management service. The backlog of events that needed to be processed from that outage on the 20th stretched our systems to the limit, and so we decided to increase our headroom for event handling throughput. When we attempted to upgrade the infrastructure on October 23, we encountered another race condition bug in Aurora RDS. This is the story of how we discovered it was an AWS bug (later confirmed by AWS) and what we learned.

background

The HiTouch Event product enables organizations to collect and centralize user behavior data such as page views, clicks, and purchases. Customers can setup sync to load events into a cloud data warehouse for analytics or stream them directly to marketing, operational, and analytics tools to support real-time personalization use cases.

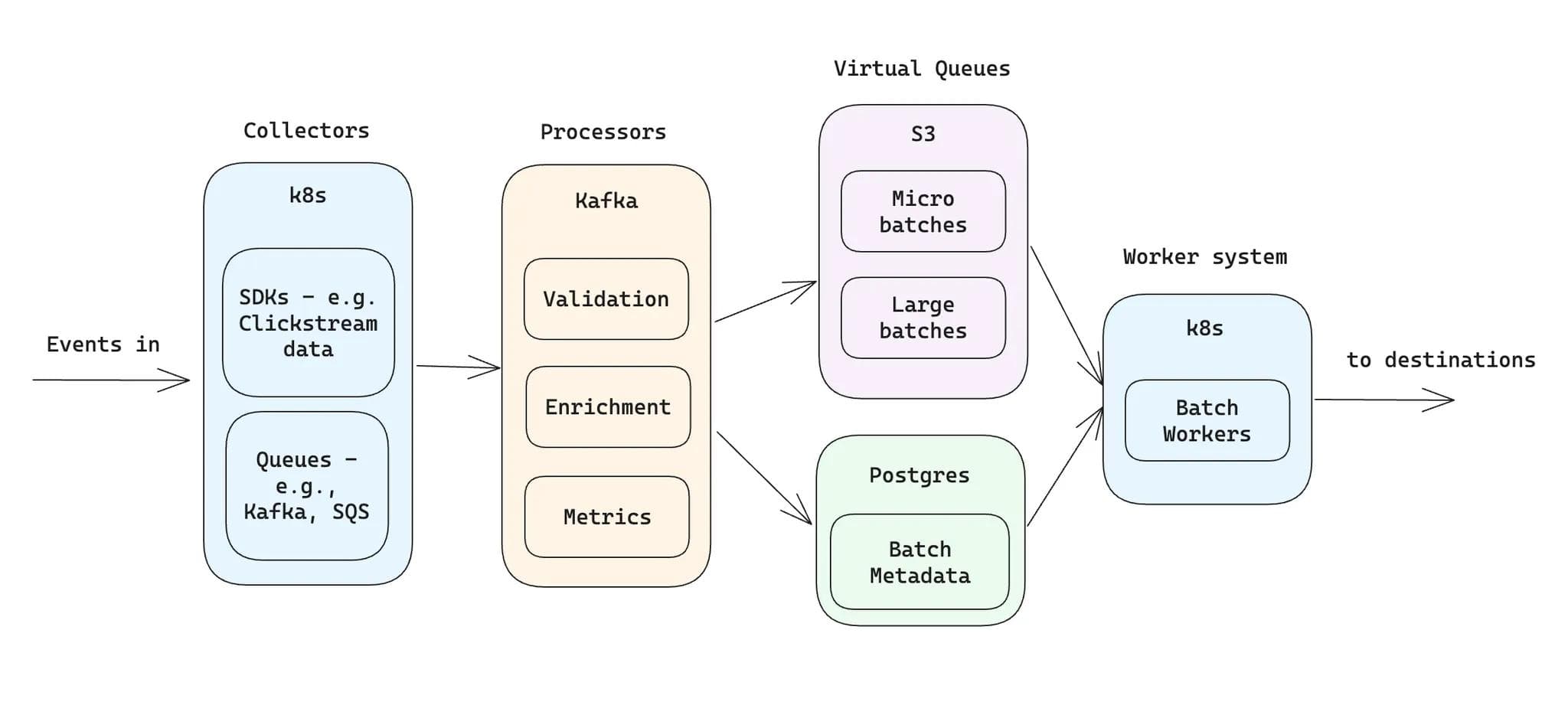

Here is the part of HiTouch’s architecture dedicated to our event system:

HiTouch Event System Architecture

Our system scales on three levers: a Kubernetes cluster containing event collectors and batch workers, Kafka for event processing, and Postgres as our virtual queue metadata store.

When our pagers went down during the AWS outage on the 20th, we saw:

- Services were unable to connect to Kafka brokers managed by AWS MSK.

- Services struggled to autoscale because we couldn’t provision new EC2 nodes.

- Client functions for realtime data changes were unavailable due to AWS STS errors, which caused our retry queues to grow large.

Kafka’s durability meant that no events were canceled after they were accepted by collectors, but there was a massive backlog to process. With consistently high traffic or with the enhancements required to call slow third party services it took longer to catch up with sync and was testing the limits of the ability of our (small) Postgres instance to act as a queue for batch metadata.

Additionally, at HighTouch, we start with Postgres wherever possible. Postgres queues serve our non-event architecture well for events scaled up to 500K events per second at ~1M sync/day and ~1s end-to-end latency on a small Aurora instance.

After watching the events of the 20th, we wanted to increase the size of the DB to give more headroom. Given that Aurora supports fast failover for scaling up instances, we decided to proceed with the upgrade on October 23 with no scheduled maintenance window.

AWS Aurora RDS

Central datastore used for real-time streaming of customer events and warehouse delivery Amazon Aurora PostgreSQL,

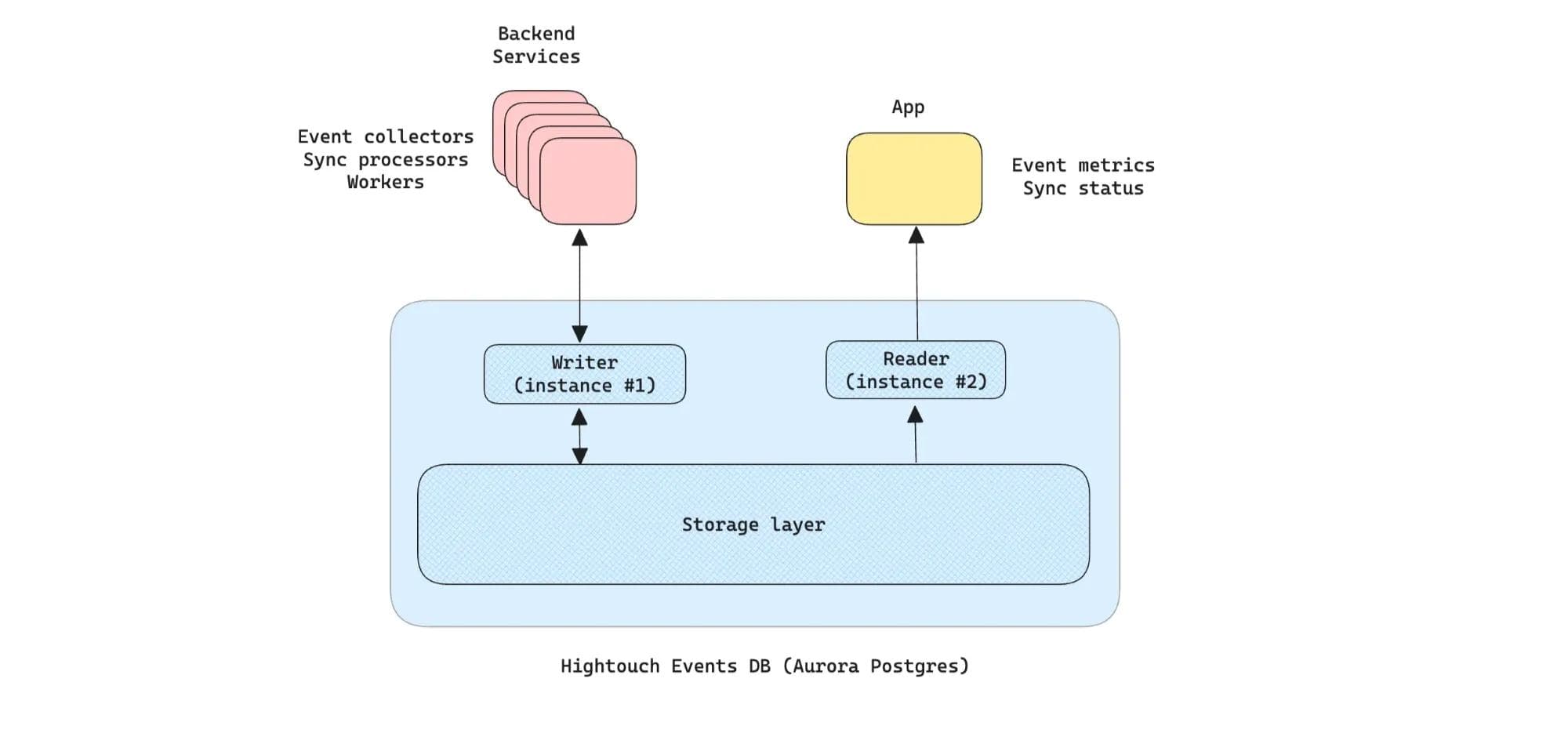

Aurora’s architecture differs from traditional PostgreSQL in one important way: it separates computation from storage. The Aurora Cluster consists of:

- a primary author example who handles all writing tasks

- multiple read replication examples which handles read-only queries

- a shared storage layer Access to all instances is automatically replicated across multiple Availability Zones

This architecture enables fast failover and efficient read scaling, but as we discovered, it also introduces unique failure modes.

A failover This is the process of promoting the read replica to become the new primary writer – usually done automatically when the primary fails, or manually triggered for maintenance operations like ours. When you trigger failover in the AWS console:

- Aurora designates a read replica as the new primary

- The storage layer grants write privileges to the new primary.

- Cluster endpoint points to new writer

- The old primary becomes a read replica (if it’s still healthy)

The diagram below shows how HighTouch Events uses Aurora.

How does HighTouch Events use Aurora?

Plan

This was our upgrade plan:

- Add another read replica (instance #3) to maintain read capacity during the upgrade.

- Upgrade the existing reader (example #2) to the target size and give it the highest failover priority.

- Trigger failover to promote instance #2 as the new writer (expected downtime less than 15s, handled decently by our backend).

- Upgrade the old writer (example #1) to match the size and make it a reader.

- Delete the temporary additional reader (Example #3).

The AWS docs supported this approach and we had already successfully tested the process in a staging environment when performing load testing, so we were confident in the correctness of the process.

upgrade attempt

On October 23, 2025 at 16:39 EDT, we triggered a failover in newly-upgraded instance #2. The AWS console showed typical progress: parameter adjustments, instance restarts, general status updates.

Then the page refreshed. Example #1 – The original author was still primary. there was a failover turned myself upside down,

According to AWS everything was healthy. The cluster appeared healthy across the board. But our backend services could not execute the written query. Restarting the services cleared the errors and restored normal operation, but the upgrade had failed.

We tried again at 16:43. Same result: brief promotion followed by immediate reversal.

Two failed failovers in five minutesNothing else had changed – no code updates, no unusual queries, no traffic spikes, We successfully tested this exact process in a staging environment under load earlier in the day, We checked our process to see if we made any mistakes, We searched online to see if anyone else had encountered this problem, but couldn’t find anything, Couldn’t find anything to explain why Aurora was refusing to complete the failover in this cluster, We were confused,

Test

We first checked the database metrics for anything unusual. There was an increase in connection count, network traffic, and throughput committed to read replicas (example #2) during failover.

High commit throughput may be due to replication or execution of write queries. The other two metrics only indicated higher query volumes.

We checked read query traffic from the app (graph below), and found no change during this period. This showed us that the additional traffic on instance #2 came from our backend services that need to connect to the Writer instance.

Inquire about traffic from HiTouch app

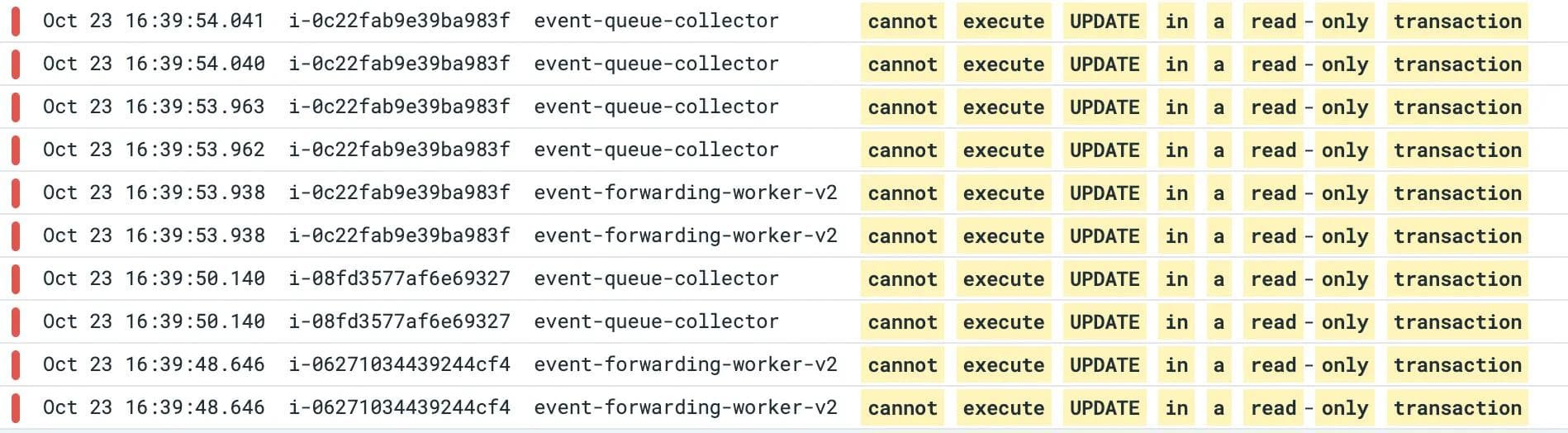

When we looked at the backend application log, we found this error –DatabaseError: cannot execute UPDATE in a read-only transaction In Some? pod.

backend application log

Our services do not connect directly to the Writer instance, but rather to a cluster endpoint that points to the Writer. This could mean one of 3 things:

- Pods did not receive a signal that the writer changed – i.e. the cluster did not terminate the connection.

- The cluster endpoint incorrectly points to the reader instance.

- The pod was connected to the writer, but the write operation was rejected at runtime.

We found no evidence supporting or refuting #1 in the application logs. We strongly suspected it was either #2 or #3. We downloaded the database logs to take a closer look and found something interesting. In both the promoted reader and the original writer, we got the same order of logs:

2025-10-23 20:38:58 UTC::@:[569]:LOG: starting PostgreSQL...

...

...

...

LOG: database system is ready to accept connections

LOG: server process (PID 799) was terminated by signal 9: Killed

DETAIL: Failed process was running: <write query from backend application>

LOG: terminating any other active server processes

FATAL: Can't handle storage runtime process crash

LOG: database system is shut down

This led us to a hypothesis:

During the failover window, Aurora briefly allowed write processing to both instances. The distributed storage layer rejected concurrent write operations, causing both instances to crash.

We expect Aurora’s failover orchestration to look something like this:

- Stop accepting new writing. Customers can expect connection errors until the failover is complete.

- Finish processing in-flight write requests.

- Demote the author and also demote the reader.

- Accept new writing requests on New Writer.

It was clearly a race situation between stages 3 and 4.

hypothesis testing

To validate the theory, we conducted a controlled failure attempt. This time:

- We have minimized all services writing to the database

- We triggered failover again

- We monitored storage runtime crashes

after finishing concurrent writesFailover completed successfully. This strongly reinforced the race-status hypothesis.

AWS confirms root cause

We delivered the findings and log patterns to AWS. After internal review, AWS confirmed that:

The root cause was due to an internal signaling problem in the old writer’s demotion process, resulting in the writer remaining unchanged after a failure.

They also confirmed that there was nothing unique about our configuration or usage that would trigger the bug.The circumstances that led to this were not under our control,

AWS has indicated that there is a fix on their roadmap, but so far, the recommended mitigation aligns with our solution: Use Aurora’s failover feature on an as-needed basis and ensure that no writes are executed against the DB during failover.

final stage

With understanding and mitigating race conditions, we:

- Cluster successfully upgraded in

us-east-1 - Updated our internal playbook Deliberately Prevent Writers Before Failure

- Added monitoring to detect any unexpected author role ad flips

takeaway

The following principles were reinforced during this experience:

- Be prepared for the worst in any migration – you may end up in your desired end state, starting state, or in-between state – even with services you trust. Making sure you’re prepared to redirect traffic and handle brief interruptions in dependability will minimize downtime.

- The importance of good observation cannot be emphasized enough. The “brief author ads” were only detectable because we were monitoring queries for each instance in Datadog and had access to the database logs in RDS.

- For large-scale distributed systems, isolating the impact any one component has on the system can help with both uptime and maintainability. It helps a lot if the design allows such events without completely shutting down the system.

- Test setups are not always representative of the production environment. Even though we practiced the upgrade process during load testing in a staging area, we could not reproduce the exact conditions that caused the race condition in Aurora. AWS confirmed that there was nothing specific about our traffic patterns that would trigger this.

If challenges like this one sound interesting, we encourage you to check out our careers page