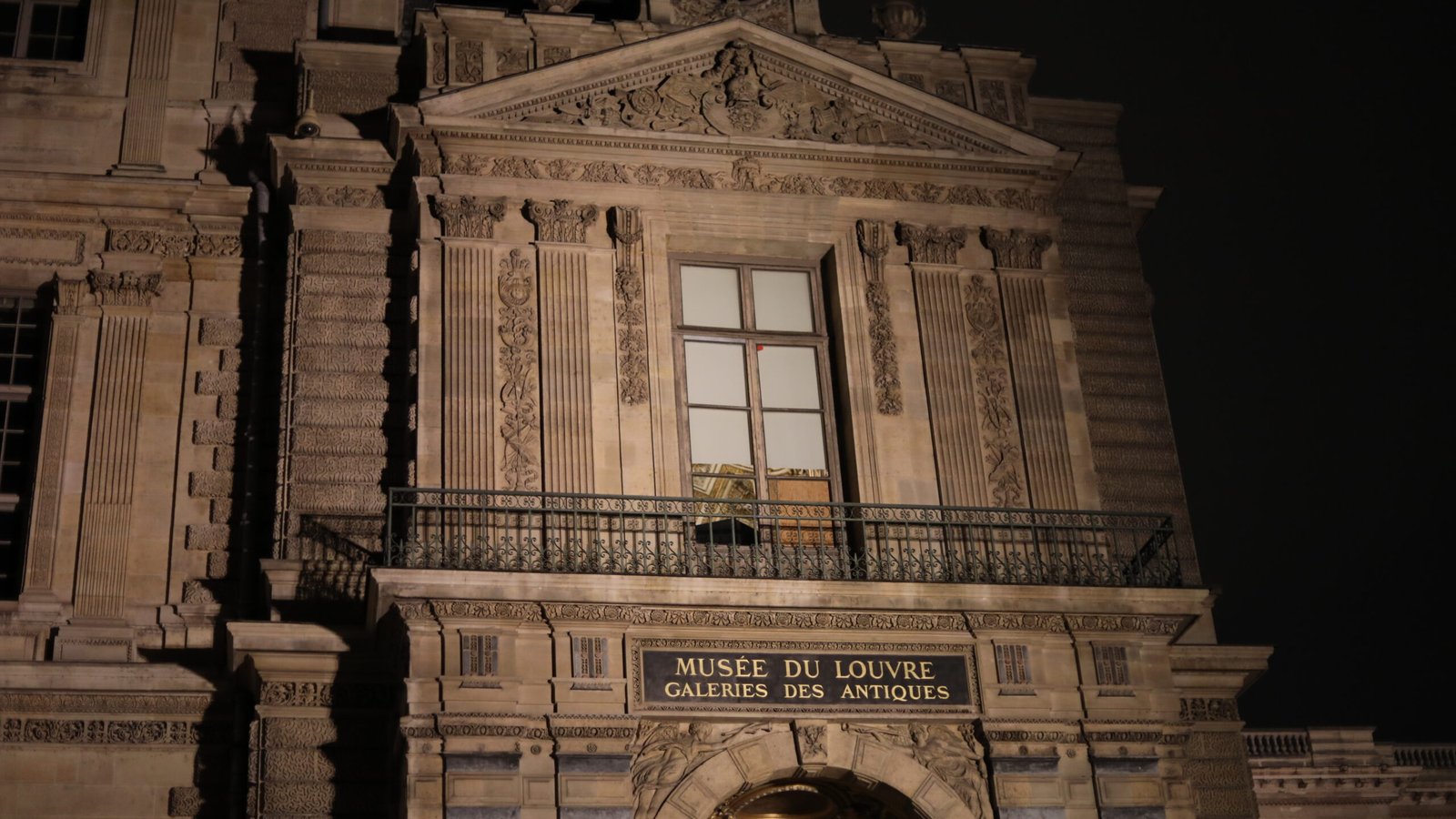

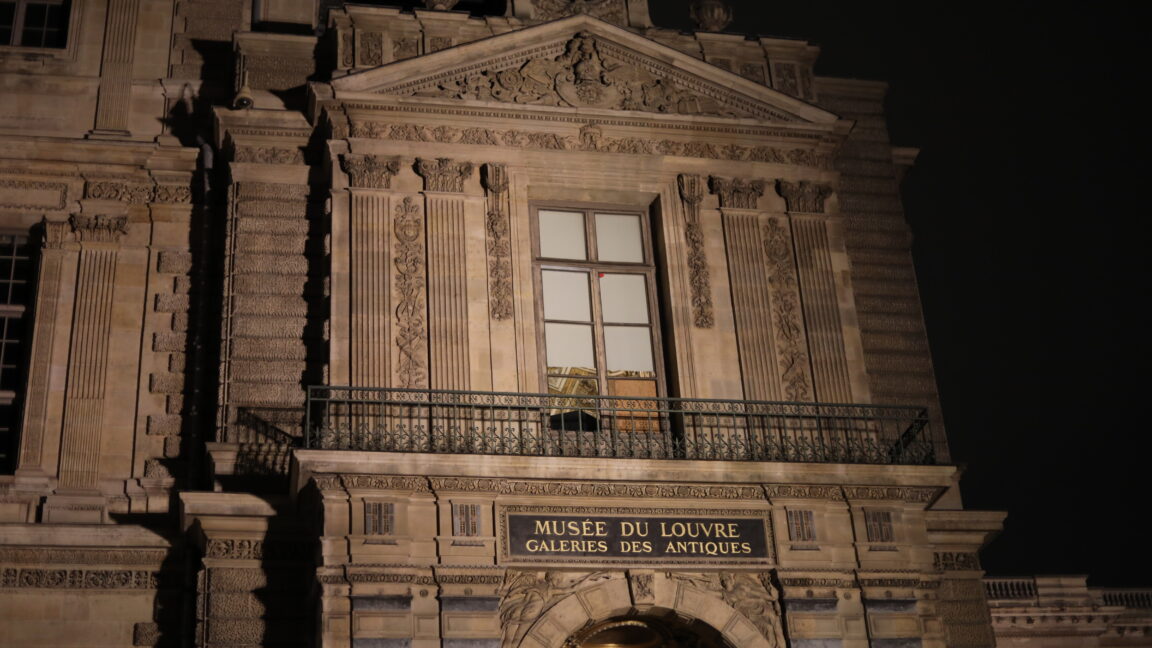

on a sunny day On the morning of October 19, 2025, four men reportedly walked into the world’s most visited museum and a few minutes later walked away with the crown jewels worth 88 million euros ($101 million). The theft from Paris’s Louvre Museum, one of the world’s most monitored cultural institutions, took just less than eight minutes.

Visitors kept browsing. Security did not respond (until alarm was triggered). Before anyone knew what had happened, they disappeared into the city traffic.

Investigators later revealed that the thieves wore high-vis jackets to disguise themselves as construction workers. They arrived with a furniture lift, a common sight in the narrow streets of Paris, and used it to reach a balcony overlooking the Seine. Dressed as laborers, they looked as if they belonged to them.

This strategy worked because we don’t see the world objectively. We see it through categories – through what we expect to see. Thieves understood the social categories we consider “normal” and exploited them to avoid suspicion. Many artificial intelligence (AI) systems work in the same way and as a result are susceptible to the same types of mistakes.

Sociologist Erving Goffman described what happened in the Louvre using his concept of self-presentation: People “perform” social roles by adopting cues that others expect them to play. Here, the display of mediocrity became the perfect camouflage.

sociology of vision

Humans make mental classifications all the time to understand people and places. When something fits the category of “normal”, it slips out of focus.

AI systems used for tasks like facial recognition and detecting suspicious activity in public areas work in a similar way. For humans, classification is cultural. For AI, it’s mathematical.

But both systems rely on learned patterns rather than objective reality. As AI learns from data who looks “normal” and who looks “suspicious,” it absorbs the categories implicit in its training data. And this makes it vulnerable to bias.

The Louvre robbers were not seen as dangerous because they fell into a trusted category. In AI, the same process can have the opposite effect: people who do not fit statistical norms become more visible and are excessively scrutinized.

This could mean that facial recognition systems flag certain racial or gender-based groups as potential threats while ignoring others.

A sociological perspective helps us see that these are not separate issues. AI does not invent its own categories; This is our learning. When a computer vision system is trained on security footage where “normal” is defined by particular bodies, clothing, or behavior, it reproduces those perceptions.

Just as museum guards kept an eye out for thieves because they appeared to be related, AI can pick up on certain patterns while overreacting to others.

Classification, whether human or algorithmic, is a double-edged sword. It helps us process information quickly, but it also codes our cultural perceptions. Both people and machines rely on pattern recognition, which is an efficient but imperfect strategy.

The sociological view of AI treats algorithms as mirrors: they reflect our social categories and hierarchies. In the Louvre case, the mirror is turned towards us. The robbers succeeded not because they were invisible, but because they were seen through the prism of normality. In terms of AI, they passed the classification test.

From museum halls to machine learning

This link between perception and classification reveals something important about our increasingly algorithmic world. Whether it’s a guard deciding who looks suspicious or an AI deciding who looks like a “shoplifter”, the underlying process is the same: grouping people into categories based on cues that seem objective but are culturally learned.

When an AI system is described as “biased,” it often means that it reflects those social categories too faithfully. The Louvre robbery reminds us that these categories not only shape our perspective, they also shape what is paid attention to.

After the theft, France’s culture minister promised new cameras and tighter security. But no matter how advanced those systems become, they will still rely on classification. Someone, or something, has to decide what counts as “suspicious behavior.” If that decision is based on assumptions, the same blind spots will remain.

The Louvre robbery will be remembered as one of Europe’s most spectacular museum heists. The thieves succeeded because they mastered the sociology of appearance: they understood the categories of normality and used them as tools.

And in doing so, they showed how both people and machines can mistake conformity for safety. Their success in daylight was not the only victory of the plan. It was a triumph of clear thinking, the same logic that underlies both human perception and artificial intelligence.

The lesson is clear: Before we can teach machines to see better, we must first learn to question how we see.

Vincent Charles, Reader in AI for Business and Management Sciences, Queen’s University Belfast and Tatiana Gherman, associate professor of AI for Business and Strategy, University of Northampton.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.