In a safe Rochester, New York, In the office basement, a refrigerator-sized nuclear device that spent three decades quietly firing neutrons without any fuss for Eastman Kodak. But after it was sealed and shipped, an employee mentioned it to a reporter. Word spread, alarms went off in newsrooms, and even CNN jumped in to cover the story: Kodak was using weapons-grade uranium in its labyrinthine research laboratories.

But the truth about the reactor was even stranger and weaker than the headlines.

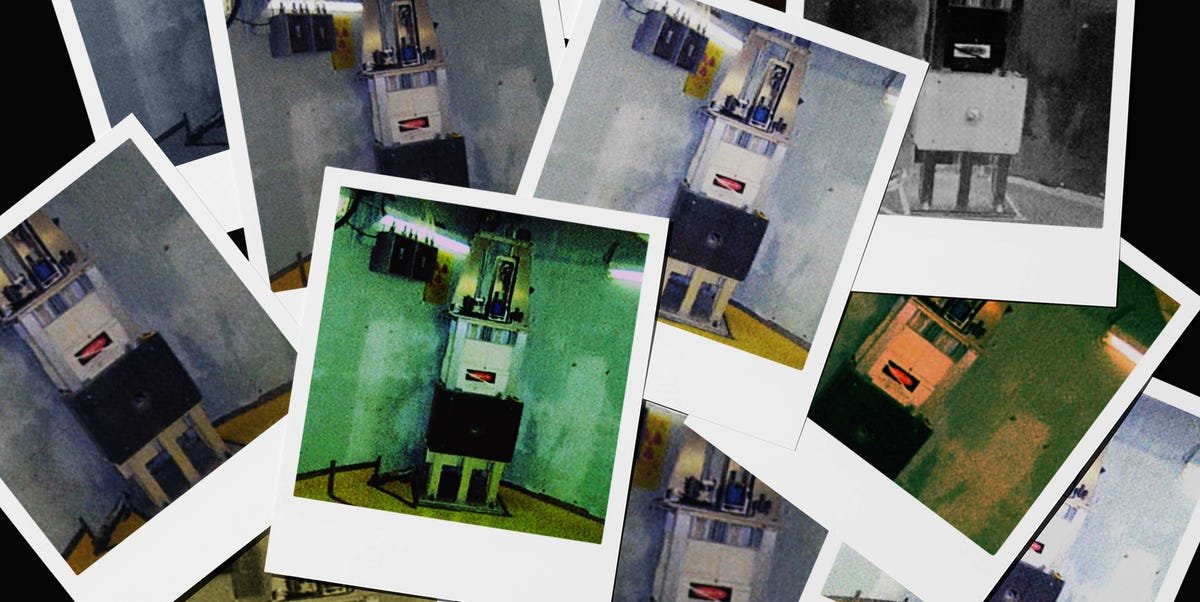

In 1975, Kodak operated the nation’s first California Neutron Flux Multiplier (CFX). Although it couldn’t live up to the sci-fi promise of its name, it did take advantage of a neat trick of nuclear engineering to provide Kodak R&D with an ample stream of neutrons for materials analysis.

CFX served two purposes: neutron activation analysis and neutron radiography. The former allowed Kodak to test chemicals for impurities. By bombarding a sample with neutrons, its elements form radioactive isotopes that emit gamma rays. Researchers can measure the energy levels of gamma rays to find out what the sample is actually made of.

The analysis was convenient to have handheld, but neutron radiography was a superpower for a private company. Although it works similarly to X-rays, neutrons interact with nuclei and X-rays interact with electrons. This means that while X-rays are powerful tools for examining heavy elements with abundant electrons, lighter elements and compounds, such as water or films, are washed out in the images. This is not the case with neutrons. If an X-ray shows you a crack in a pipe, a neutron will show you a leak.

The really impressive part was how Kodak’s machine achieved its stream of neutrons. It used the spontaneous fission of californium-252 (CF-252). The isotope created in the laboratory sheds neutrons in the same way as a husky sheds its fur in July. However, this fountain of neutrons was too expensive to be the sole source (today it costs about $30,000 per milligram). So the designers of CFX looked at a fission standard: highly enriched uranium (HEU).

Neutrons will exit the tiny CF-252 source – about 3.1 mg in the device’s core – and pass through 52 plates of highly enriched uranium. Behind lead shielding, neutrons collide with HEU atoms to produce unstable nuclei. These often, but not always, break into lighter fragments, releasing two or three more neutrons as well. When the stream reached the sampling port, the flux was 30 times higher than that of CF-252 alone.

At first glance it might appear worryingly similar to a nuclear reactor: uranium fuel plates, fission neutrons, heavy shielding. The key difference is that the CFX was deliberately engineered to remain subcritical so that each fission produces fewer neutrons than needed to sustain a chain reaction. Without feeding the CF-252, the process terminates.

From 1975 to 2006, the CFX operated within its two-foot-thick walls and government-approved security protocols. Approximately every seven years, the CF-252 source was replenished. And apart from a license renewal glitch in 1980, the device made no stir until its existence was shared with a local newspaper – it was not a secret, just unpublicized.

Not surprisingly, when news of Kodak’s CFX spread across the country in 2012, most outlets focused on the dangers of HEU rather than its potential to generate neutron flux. In fact, it is hard to trust private corporations with the stuff that makes nuclear bombs today. But CFX was founded at a time of nuclear optimism, where it was standard for top-tier universities to run reactors and ambitious companies wanted to harness nuclear power.

According to Kodak and officials, within its bunker, CFX was a strictly regulated non-hazard. The biggest threat came in decommissioning in 2007. An old CFX is the industrial laboratory equivalent of the asbestos-coated pipe in your basement. It is completely safe until you decide to delete it.

While the CF-252 component weighed about the same as an ice cube, the HEU was a more significant 3.5 pounds. And although it takes about 100 pounds to make a nuclear bomb, the fear is that bad actors will work with a quantity small enough to create a weapon. The plates were discreetly transported to a government facility, under Department of Energy investigation. As evidence of the security involved, no public records reveal who actually moved the plates, or how they moved them beyond safety protocols, using tongs and a shield made of plexiglass – which is surprisingly capable of slowing down the neutrons and alpha radiation of HEU.

The real story of Kodak’s Flux Multiplier is less a conspiracy than a technical curiosity. It was a unique example of Cold War-era engineering, housed within a corporate complex subject to strict government oversight. The building has been sold by Kodak and the room has long ago been declared safe, despite some isotopes being active in the concrete. But it’s a reminder that the bleeding edge of technology was once radioactive.

Matt Allyn wrote and edited for men’s Health, men’s journal, men’s fitness, bicycling, popular mechanicsAnd runner’s world Magazines. He has run 10 marathons and has come very close to becoming BQ three times. In addition to running, cycling, and never leaving a leg during the day, he has also been brewing beer for nearly two decades and is a certified beer judge.