I liked the rhythm and immediacy of it. But I still didn’t know what it meant to be angry from inside the belly of the beast.

I will learn soon.

When education is not enough

I began studying law while in solitary confinement at the Hudson County Correctional Facility in Kearny, New Jersey. At 25, I was educated, street-smart, well-traveled, well-read, and ran a successful business selling phones and laptops. And yet, I couldn’t follow the jargon in court. It seemed like a strange language that everyone else spoke fluently. I asked my lawyers some questions, but I did not press. I was new. I trusted him.

It’s a mistake that still haunts me. If I had known what I know now, I would have emphasized different strategies in court to fight my case. If I had done that, I don’t think I would have been sentenced to two consecutive life sentences – 150 years in prison.

You see, the system wants you to sit down, shut up, and comply. But every wrong step hangs around your neck like a noose. And when your lawyer fails you, if you try to appeal, the court’s starting point is “accurate trial strategy”, meaning they believe defense counsel did their job well to begin with.

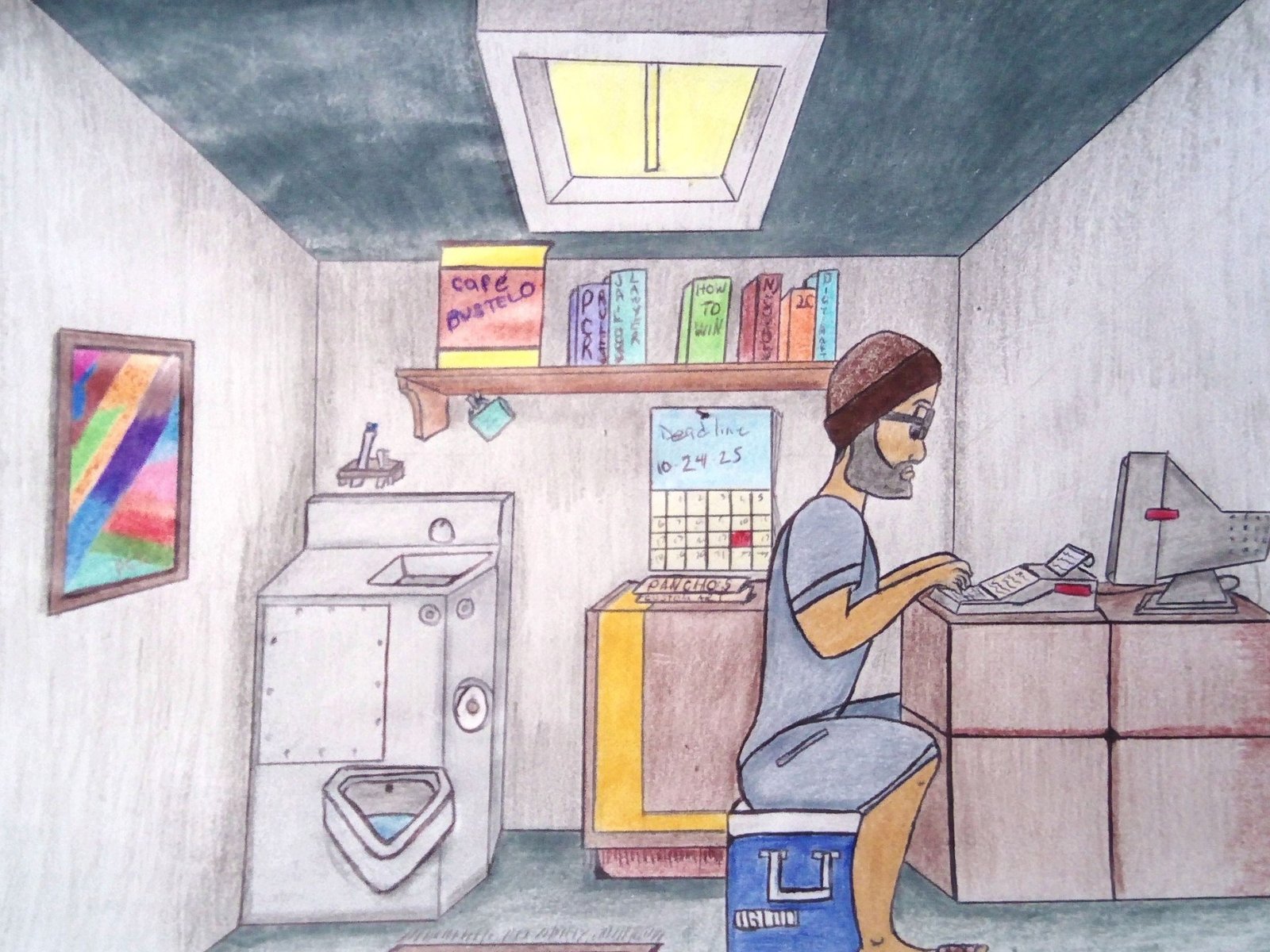

In the law library: no saviors, just strategies

When I arrived at the New Jersey State Prison (NJSP) in Trenton in 2005, an elderly inmate told me, “Your job is to stay out of trouble, survive, and fight for your life. There is no one to save. Go to the law library and learn.”

So I joined the inmate-run paralegal group, the Inmate Legal Association (ILA). They trained me and I became an uncertified paralegal.

Soon after joining ILA, I started my legal fight and started helping others. My first victory was a procedural motion that helped a fellow prisoner get back into court. That memory still sits in my mind like a trophy. Helping someone else made the struggle worthwhile.

Another victory came in federal prison court, where I wanted to appeal my conviction. My petition was rejected. But I appealed. I was confident in my research. I filed. And I won. There was no result and the petition was later dismissed. But the short-term victory meant something: We could push back.

Resistance hidden behind bars

This is the life of a pro se litigant – pro se means “for oneself” in Latin – someone who represents oneself in court. Serving as your own legal counsel is rarely an option; More often than not, it’s a necessity. I hired my own attorney, and the state hired a second attorney for my trial and initial appeals. After that, I was on my own. I could no longer afford legal representation. And I am far from alone.

Thousands of lawsuits are filed every year by people in jail. US court data from 2000-2019 shows that 91 percent of legal challenges by prisoners were filed pro se.

This is not a new thing. A report by the Bureau of Justice Statistics in the mid-1990s showed that 93 percent of federal habeas corpus petitions filed by state prisoners were also professional.

These numbers confirm what we see inside: Legal representation almost ends after the first appeal, and besides, we are on our own, with no training, limited resources, and enormous obstacles.

Voices from the legal underground

Take Martin Robles, a 52-year-old Puerto Rican who has spent nearly 30 years behind bars. Once he could not afford a lawyer, Martin took charge of his appeals. “Courts don’t follow their own rules,” he told me. “They don’t hold prosecutors accountable like we do. We get time-outs imposed (and appeals denied) for being an hour late. But prosecutors? They get unlimited leeway.”

Courts do not care about the difficulties prisoners face communicating with paralegals or researching case law to prepare legal briefs. To top it all, access to the law library has been reduced. We have to request a pass to visit during our housing unit’s weekly rotation, but passes are limited, and sometimes we wait weeks to enter the library. Courts routinely impose time limits on prisoners that are impossible to meet, yet fail to make any allowance for the constraints of prison. For example, a friend was given a month to file legal briefs, but during this time he was not allowed to visit the prison library because his arm was in a cast, and it was considered a potential weapon. But without access to a library, he could not seek help from paralegals, consult legal reference books, or use a computer to type his brief. The deadline passed, and he wrote to the judge about his plight, but was not granted an extension.

Martin has turned his anger into something productive. “I am starting the first Spanish-language law class at NJSP,” he said.

“It’s voluntary. I’m doing it for the people. I’m tired of them being taken advantage of.”

When money can’t buy security

Kashif Hasan, 39, entered the system with a master’s degree and hired private lawyers. “I threw money at lawyers and thought I was good,” he said. “But I was manipulated and betrayed. I didn’t fight fast enough.”

Eventually, Kashif took up legal lessons and took charge of his own future. “My first victory was a bail plea in the county (jail),” he said.

“If you won’t fight, no one else will. If you know what you’re doing, professional litigation works. But the courts treat us like rookies. Like we don’t count.”

A lawyer who did not prepare for the defense

Tommy Koskovich, 47, was arrested at the high school. “My lawyer made fun of me,” he recalled. “Was told he wasn’t getting paid enough from the public defender’s office so he didn’t prepare a defense. When I refused the plea deal, he said, ‘I didn’t prepare a defense for you.'”

Tommy subsequently lost all of his appeals, but is now pursuing his only remaining option: a motion to overturn his conviction and pardon. He has also applied for the latter through New Jersey’s new clemency initiative.

Throughout the process, Tommy has learned to identify legal issues. “Sometimes the courts will only take your case seriously if you file a lawsuit,” he said. “That’s how State v. Comer happened, where an inmate brought up the issue himself.”

James Comer was 17 years old when he was convicted of aggravated murder and other crimes in 2000 after carrying out several armed robberies with two other men. He was sentenced to prison until the age of 85. He would likely have died in prison, but he took his fight to the New Jersey Supreme Court with his lawyers and was disbarred. He was released in October after serving a 25-year sentence.

Martin, Kashif and Toomey reflect what many of us behind the wall already know: The system isn’t built for justice — it’s built for conviction. The moment your initial appeals wear off, you will be on your own.

Every mistake you make is punished. Every mistake is used to close the door tightly.

Legal fight is also moral

Still we fight. We write on broken chairs under flickering lights. We teach others how to file motions, navigate case law, and explain legal jargon.

As for me, I am working on a motion for DNA testing to prove my innocence and an alternative motion to vacate my conviction. But there are some cases pending in the New Jersey Supreme Court that may help my case, so I am waiting for their results.

Because we do not remain silent.

We do not go easy on that good night.

We are angry – against wrongful convictions, indifferent courts, and a system that expects us to give up.

We get angry, even when no one is watching.

Even when no one believes.

Even when the victories are small.

After all, anger is hope in motion.

This is the first in a three-part series on how prisoners are challenging the American justice system through the law, prison hustles, and a hard-earned education.

<a href