The listing includes two entries for Mobile Fortify – one for Customs and Border Protection (CBP), the other for Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) – and says the app is in the “deployment” phase for both. CBP says Mobile Fortify became “operational” in early May last year, while ICE got access to it on May 20, 2025. This date is approximately a month before 404 Media first reported on the existence of the app.

The inventory also identified the vendor of the app as NEC, which was previously unknown to the public. On its website, NEC advertises a facial recognition solution called Reveal, which it says can perform one-to-many searches or one-to-one matching against databases of any size. CBP says the vendor of the app is NEC, while ICE says it was partially developed in-house. The $23.9 million contract between NEC and DHS from 2020 to 2023 stated that DHS was to use NEC biometric matching products “for an unlimited amount of faces, on unlimited hardware platforms, and in unlimited locations.” NEC did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

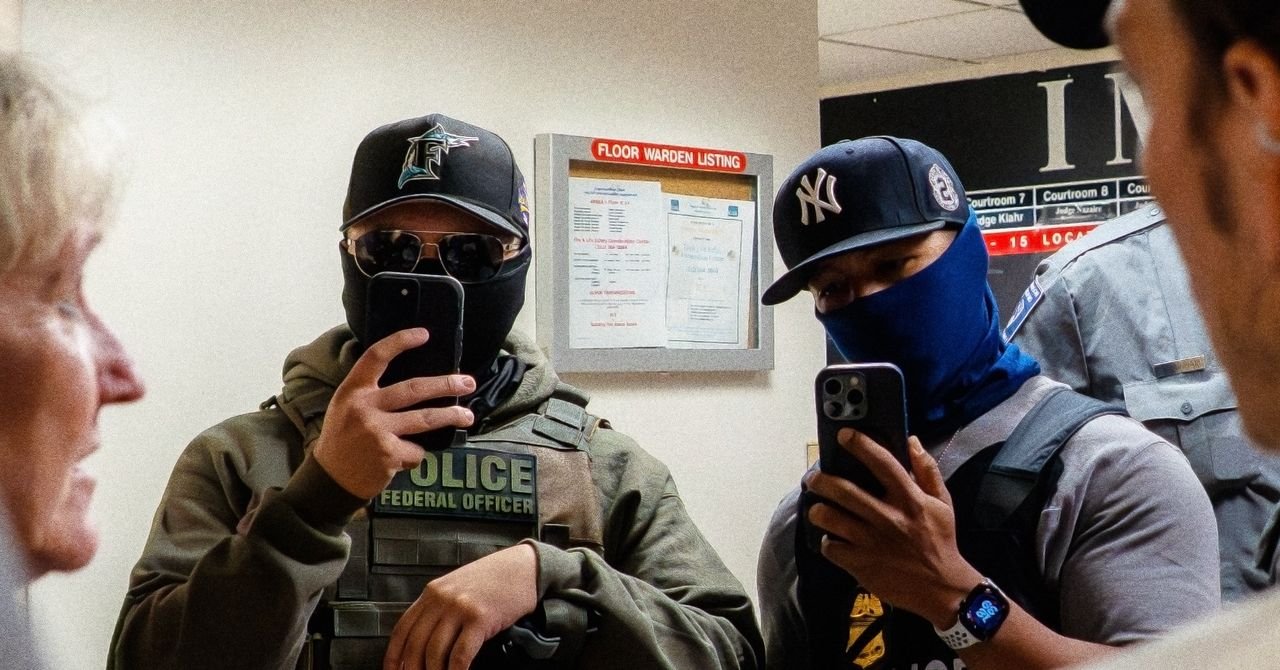

Both CBP and ICE say the app helps quickly confirm people’s identities, and ICE further says it helps do so in the field “when officers and agents have to work with limited information and have access to many different systems.”

ICE says the app can capture photos of faces, “contactless” fingerprints and identification documents. The app sends that data to CBP “for submission into the Government biometric matching system.” Those systems then use AI to match people’s faces and fingerprints with existing records, and return potential matches with biographical information. ICE says it also extracts text from identification documents for “additional investigation.” ICE says it does not own the AI models or interact with them directly, and they belong to CBP.

CBP says “vetting/border crossing information/credible traveler information” was used to train, fine-tune, or evaluate the performance of Mobile Fortify, but it did not specify which, and did not respond to WIRED’s request for clarification.

CBP’s Trusted Traveler programs include TSA PreCheck and Global Entry. In an announcement earlier this month, a Minnesota woman said her Global Entry and TSA PreCheck privileges were revoked after a conversation with a federal agent she was seeing who told her he had “facial recognition.” In another announcement of a separate lawsuit filed by the state of Minnesota, a man who was stopped and detained by federal agents says an officer told him, “Anyone who is the registered owner [of this vehicle] It will be fun to try traveling after this.”

While CBP says there are “adequate monitoring protocols” for the app, ICE says development of monitoring protocols is in progress, and it will identify potential impacts during an AI impact assessment. According to guidance from the Office of Management and Budget, which was issued before the inventory was deployed to CBP or ICE, agencies are required to complete an AI impact assessment. First Deploying to any high-impact use case. Both CBP and ICE say the app is “high-impact” and “deployed.”

DHS and ICE did not respond to requests for comment. CBP says it plans to look into WIRED’s investigation.

<a href