Researchers used Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL)’s exascale supercomputer El Capitan to conduct the largest fluid dynamics simulation to date – exceeding a quadrillion degrees of freedom in a single computational fluid dynamics (CFD) problem. The team focused efforts on rocket-rocket plume interactions.

El Capitan is funded by the Advanced Simulation and Computing (ASC) program of the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA). The work – partly conducted in advance of the change in the classified operations of the world’s most powerful supercomputer earlier this year – is led by researchers at Georgia Tech and supported by partners at AMD, NVIDIA, Apache, Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL) and New York University’s (NYU) Courant Institute.

This paper is a finalist for the 2025 ACM Gordon Bell Award, the highest honor in high-performance computing. this year’s winner — selected from among a handful of finalists — will be announced Nov. 20 at the International Conference for High-Performance Computing, Networking, Storage, and Analytics (SC25) in St. Louis.

To tackle the extreme challenge of simulating the turbulent exhaust flow generated by multiple rocket engines firing simultaneously, the team’s approach combined a newly proposed shock-regularization technique called information geometric regularization (IGR), which was invented and implemented by Professor Spencer Bringelson of Georgia Tech, Florian Schaefer of NYU Courant, and Ruijia Cao (now a Cornell PhD student).

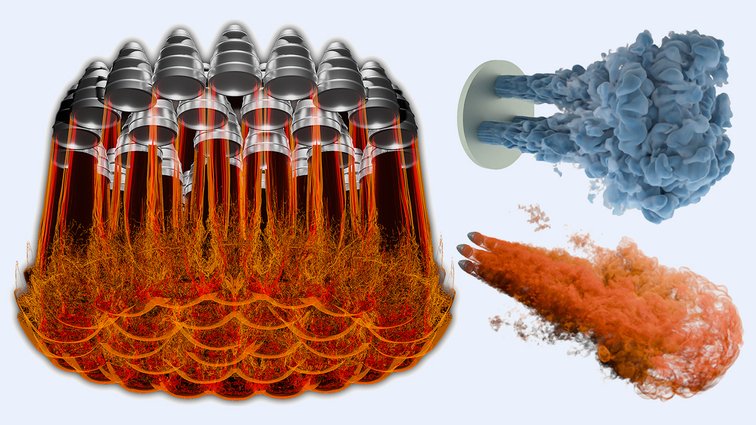

Using all 11,136 nodes and more than 44,500 AMD Instinct MI300A Accelerated Processing Units (APUs) on El Capitan, the team achieved 500 trillion grid points or better than 500 quadrillion degrees of freedom. They extended it to ORNL’s Frontier, overcoming a quadrillion degrees of freedom. The simulations were conducted with MFC, a licensed open-source code maintained by Bringelson’s group. With these simulations, they represented the full exhaust dynamics of a complex configuration inspired by SpaceX’s Super Heavy booster.

The simulation sets a new benchmark for exascale CFD performance and memory efficiency. According to the team, it also paves the way for computation-driven rocket design, replacing expensive and limited physical experiments with predictive modeling at unprecedented resolution.

The project leader, Georgia Tech’s Bringelson, said the team used special techniques to make efficient use of El Cap’s architecture.

“In my view, this is an interesting and remarkable advancement in the fluid dynamics field,” said Bringelson. “This method is fast and simple, uses less energy on El Capitan, and can simulate much larger problems than prior state-of-the-art – Order of magnitude larger.

The team gained access to El Capitan through prior collaboration with LLNL researchers and worked with LLNL’s El Capitan Center of Excellence and Apache to use the machine on a classified network. LLNL facilitated the effort as part of system-scale stress testing prior to El Capitan’s classified deployment, serving as a public example of the system’s full capabilities before turning it over for classified use in support of NNSA’s core mission of stockpile stewardship.

“We supported this work primarily to evaluate the scalability and system readiness of El Capitan,” said Scott Futrell, development environment group leader at Livermore Computing. “The greatest benefit of the ASC program was to expose system software and hardware problems that only become visible when the entire machine is used. Addressing those challenges was critical to operational readiness.”

While the actual computation time was relatively short, most of the effort was focused on debugging and resolving issues that arose at full system scale. Futral said internal LLNL teams working on tsunami early warning and inertial confinement fusion have also conducted full-system science demonstrations on El Capitan – efforts that reflect the lab’s broader commitment to mission-relevant exascale computing.

Next generation challenge solved with next generation hardware

As private sector space flight expands, launch vehicles are increasingly relying on compact, high-thrust engines rather than a few large boosters. This design offers manufacturing advantages, engine redundancy and easy transportation, but also creates new challenges. When dozens of engines fire simultaneously, their plumes interact in complex ways that can send scorching hot gases back toward the vehicle’s base, threatening mission success, the researchers said.

The solution depends on understanding how those plumes behave in different conditions. While wind tunnel experiments can test some physics, only large-scale simulations can see the full picture at high resolution and under changing atmospheric conditions, engine failures or trajectory variations. According to the team, until now, such simulations were too expensive and memory-intensive to run on a meaningful scale, especially in the era of multi-rocket boosters.

To break that barrier, the researchers replaced traditional “shock capturing” methods – which struggle with high computational costs and complex flow configurations – with their IGR approach, which improves how shock waves are treated in simulations to enable non-propagative treatment of the same phenomenon. With IGR, more stable results can be calculated more efficiently.

With IGR, the team focused on scale and speed. Their optimized solver took advantage of El Capitan’s unified memory APU design and mixed-precision storage via AMD’s new Flang-based compiler to pack more than 100 trillion grid cells into memory without performance degradation.

The result was a full-resolution CFD simulation that ran on the entire system of El Capitan – about 20 times larger than the previous record for this class of problem. The simulation tracked exhaust from 33 rocket engines emitting exhaust at Mach 10, capturing the moment-by-moment evolution of plume interactions and heat recirculation effects in fine detail.

At the center of the study was El Capitan’s unique hardware architecture, which is equipped with four AMD MI300A APUs per node – each combination of CPU and GPU chips directly accessing the same physical memory. For CFD problems that require simultaneous high memory load and executable computation, that design proved necessary and comparatively harmless compared to the integrated memory strategies required by separate memory systems.

The team conducted scaling tests on multiple systems, including ORNL’s Frontier and the Swiss National Supercomputing Center’s ALPS. Only El Capitan supports physically shared memory architecture. The system’s unified CPU-GPU memory, based on AMD’s MI300A architecture, allows the entire dataset to reside in a single addressable memory space, eliminating data transfer overhead and enabling larger problem sizes.

“We needed El Capitan because no other machine in the world could run a problem of this size at full resolution without any compromises,” said Bringelson. “The MI300A architecture gave us unified memory with zero performance penalty, so we could store all of our simulation data in one memory space accessible by both the CPU and GPU. This eliminated overhead, cut the memory footprint, and allowed us to scale across the entire system. El Capitan made this work not only possible; it made it efficient.”

The researchers achieved 80 times speedup compared to previous methods, reduced the memory footprint by 25 times, and reduced energy-to-solution by more than five times. By combining algorithmic efficiency with El Capitan’s chip design, they showed that simulations of this size could be completed in hours, not weeks.

Implications for space flight and beyond

While the simulations focused on rocket exhaust, the underlying method is applicable to a wide range of high-speed compressed flow problems — from aircraft noise prediction to biomedical fluid dynamics, the researchers said. The ability to simulate such flows without introducing artificial viscosity or sacrificing resolution could transform modeling in many domains and highlights a key design principle behind El Capitan: combining breakthrough hardware with real-world scientific impact.

Bronis R., Chief Technology Officer, Livermore Computing “From day one, we designed El Capitan to enable mission-level simulations that were not possible before,” de Supinski said. “We are always interested in projects that help validate large-scale performance and scientific usability. This demonstration provided insight into the behavior of El Capitan under real system stress. While we are supporting many efforts internally – including our own Gordon Bell submission – this was a valuable opportunity to collaborate and learn from an external team with a proven code.”

<a href