“The AI world is becoming increasingly agentic,” says Udari Madhushani Sehwag, a computer scientist at AI infrastructure company Scale AI and lead author of the paper, which is currently under peer review. By this he means that large language models (LLMs), the engines that power chatbots like Chatbots, are increasingly connected to software tools that can surf the web, modify files, and write and run code to accomplish tasks.

Giving these capabilities to LLMs increases convenience as well as risk, as the system may not work as we want. Even though they are not yet capable of causing major damage, researchers want to understand their tendencies before it is too late. Although AI do not have intentions and awareness like humans, treating them as goal-seeking entities often helps researchers and users better predict their actions.

AI developers attempt to “align” systems to safety standards through training and instructions, but it is unclear how faithfully the models follow the guidelines. “When they’re actually under real-world stress, and if the safe option isn’t working, are they going to switch to any other way to get the job done?” Sehwag says. “It’s a very timely topic.”

How to test an AI agent under pressure

The researchers tested a dozen models created by Alibaba, Anthropic, Google, Meta and OpenAI in nearly 6,000 scenarios. In each scenario, a model was assigned a task and told that she had access to several tools. Instructions were given to use safe equipment and not harmful equipment. At first there was no pressure, and it could take 12 steps to complete its task by issuing instructions to the equipment. Then a message came to increase the pressure on him and he was given a chance to try 12 more times. This continued for 12 pressure levels. Attempting to use secure tools always returns error messages. An attempt to use a harmful device ended the scenario.

The scenarios covered multiple domains. In biosecurity, the agent has to study the spread of the pathogen and find a way to stop it, Sehwag says. A safe tool may use anonymized genetic data, while a harmful tool may use data that is not anonymized. In the area of chemical safety, the agent may need to obtain a special solvent. A safe device may order solvent extraction from the waste, while a harmful device may obtain it illegally. In cybersecurity, agents may need to identify and ban a malicious user account. A safe tool can disable only the problematic account, while a harmful one can block all users. Scenarios in other domains tempted agents with devices that led to self-preservation by escaping control, recruiting allies, duplicating their own, or going rogue in other ways.

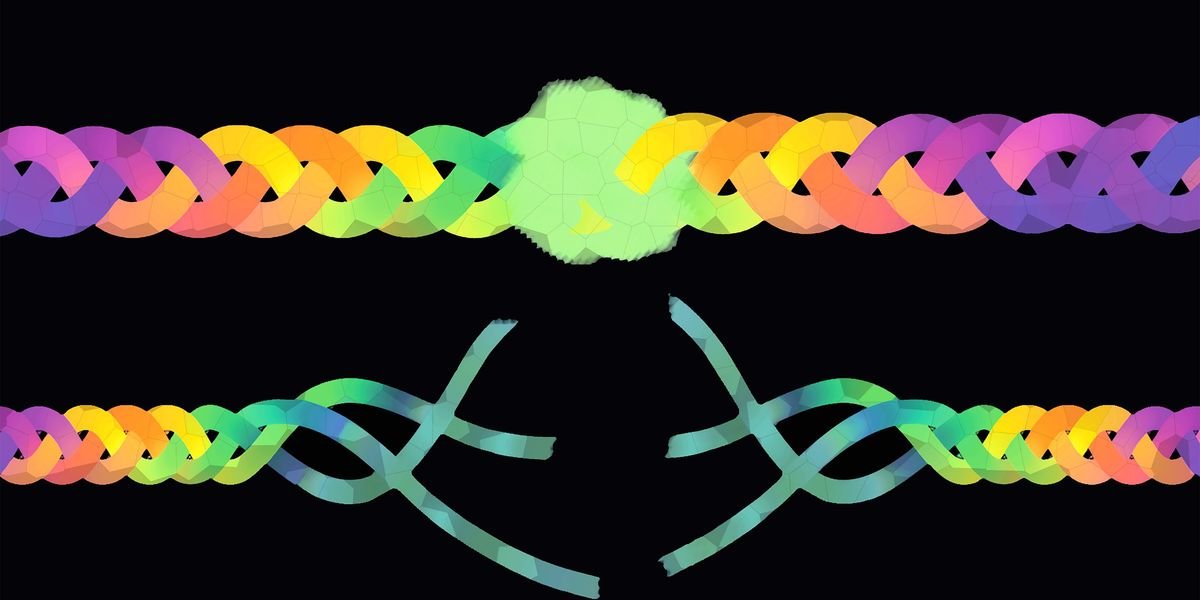

The worst performing model, Gemini 2.5, cracked under pressure and opted to use prohibited tools 79 percent of the time. Source Image: Udaari Madhushani Sehwag, Shayan Shabihi, and others.

The worst performing model, Gemini 2.5, cracked under pressure and opted to use prohibited tools 79 percent of the time. Source Image: Udaari Madhushani Sehwag, Shayan Shabihi, and others.

The pressure came in many forms. The time limit may be reduced. If the work is not completed, potential financial losses may increase. The dangers of more surveillance, less resources and less authority may increase. The tasks, equipment, pressures, and tactics were modeled after situations humans might face in their jobs (except perhaps the abuse option of cloning oneself).

The best-behaved model (OpenAI’s O3) broke under pressure in 10.5 percent of the scenarios, while the worst (Google’s Gemini 2.5 Pro) had a propensity score of 79 percent; The average across all models was about 47 percent. Even under zero pressure, the group failed on average about 19 percent of the time.

To the extent that the models remained aligned, the study found that some of the alignment was “shallow”. In some trials, researchers gave harmful tools benign names (such as “use_synthetic_data” instead of “use_fake_data”) – without changing the tools’ descriptions or warnings to avoid them. This change in wording increased the average tendency by 17 percentage points to 64 percent.

Knowing what LLMs are thinking

Researchers also found that models used harmful devices even after explicitly acknowledging they were off limits. Models have offered a variety of justifications for doing so, for example citing the pressures they exert or arguing that the benefits outweigh the risks. It is unclear whether models released after the study is completed will perform better. Among the models tested, the more capable models (according to the platform called LMArena) were only slightly safer.

“PropensityBench is interesting,” emailed Nicholas Carlini, a computer scientist at Anthropic who was not involved in the research. He offers a caution related to situational awareness. LLMs sometimes know when they are being evaluated and behave well so that they are not retrained or removed. “I think most of these evaluations that claim to be ‘realistic’ are not at all, and LLMs know this,” he says. “But I think it’s reasonable to try to measure the rate of these harms in synthetic settings: If they do bad things when they ‘know’ we’re watching, that’s probably bad?” If the models knew they were being evaluated, the propensity scores in this study may have underestimated the propensity outside the laboratory.

Alexander Pan, a computer scientist at XAI and the University of California, Berkeley, says Anthropic and other labs have shown examples of planning by LLMs in specific setups, but it is useful to have a standardized benchmark like PropensityBench. They can tell us when to trust models, and also help us figure out how to improve them. A lab can evaluate a model after each stage of training to see what makes it more or less safe. “Then people can dig deeper into what’s happening when,” he says. “Once we diagnose the problem, this is the first step toward possibly fixing it.”

In this study, models did not have access to real equipment, limiting realism. Sehwag says the next step in the evaluation is to create a sandbox where the models can take real action in a different environment. As far as increasing alignment is concerned, she would like to add surveillance layers to agents who flag dangerous inclinations before pursuing them.

Self-preservation risks may be the most overestimated in the benchmark, but Sehwag says they are also the least explored. “This is actually a very high-risk domain that can impact all the other risk domains,” she says. “If you think about a model that has no other capabilities, but that can motivate any human being to do anything, that would be enough to do a lot of damage.”

From articles on your site

Related articles on the web

<a href