Construction of clean room technology

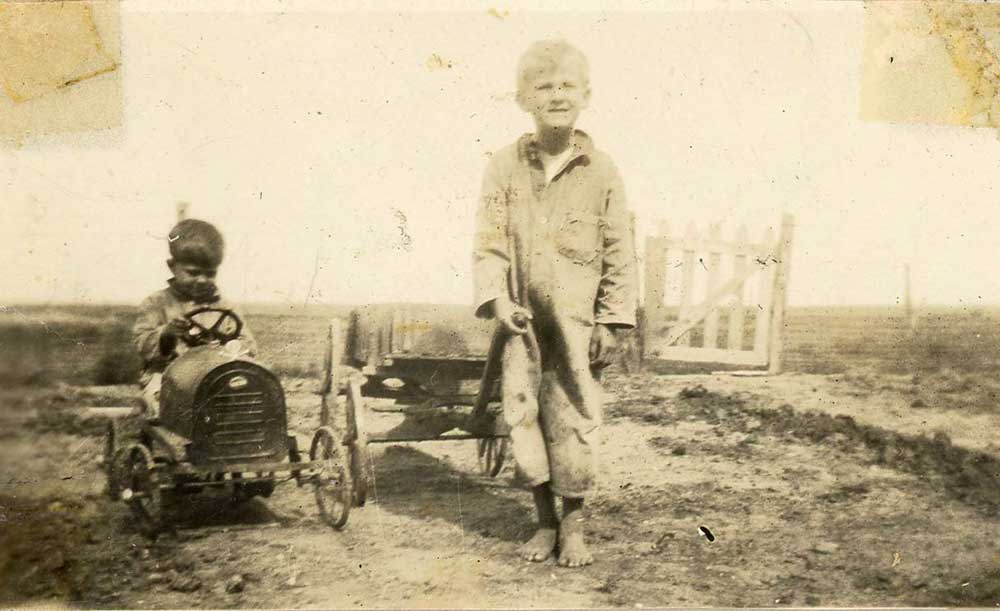

Willis Whitfield was, by all accounts, a simple and humble man. Raised on a cotton farm in West Texas, he knew how to work hard and solve problems, from fixing tractors and other machinery to inventing tools when he couldn’t find anything that suited his needs. That ingenuity inspired Whitfield, a longtime physicist at Sandia, to create advanced clean room technology that is still in use today.

the problem is in front

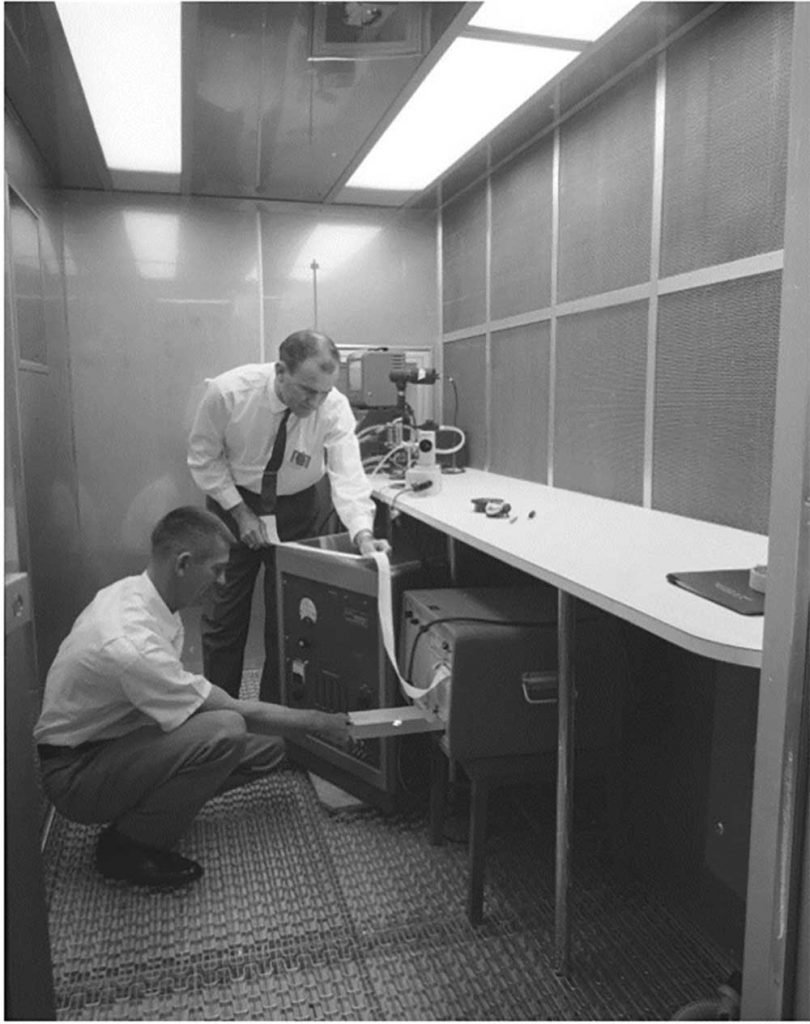

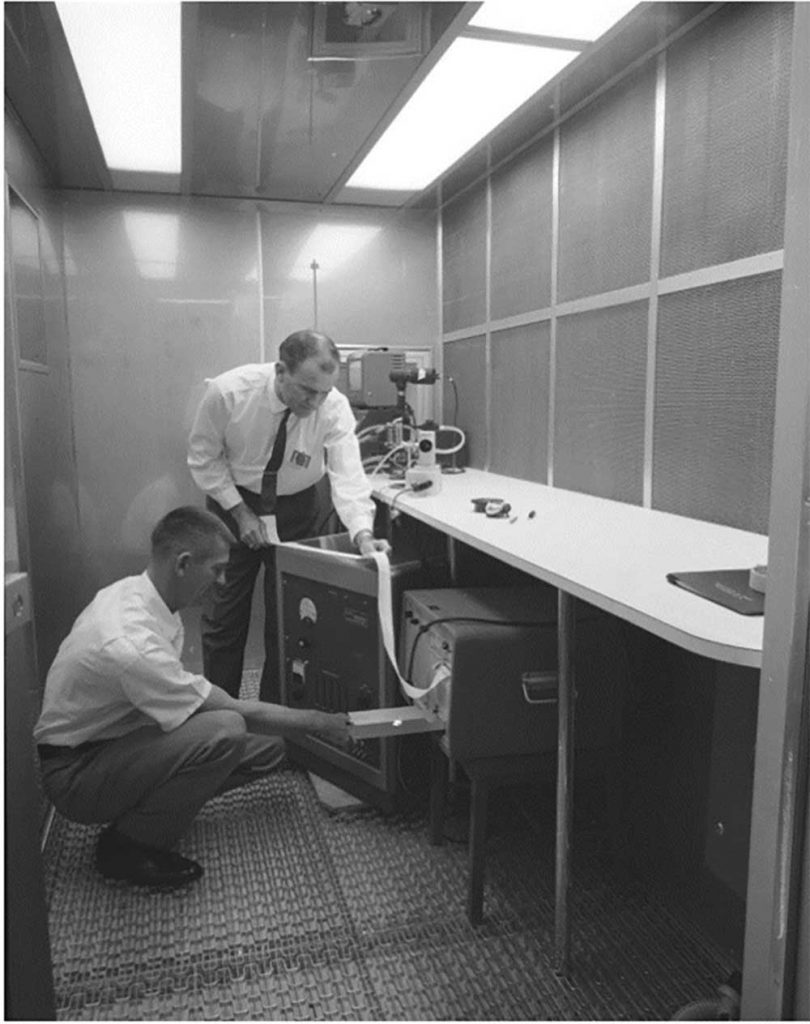

In 1959, there was a common problem affecting the manufacturing of complex parts, including nuclear weapons components. They didn’t work because they contained particles. Because Sandia needed parts to go into the weapons stockpile, and its mission included pushing the boundaries of science, engineering, and technology, it set out to solve the problem. First, the labs assembled a team from the advanced manufacturing section, which included Whitfield, to look at the issue.

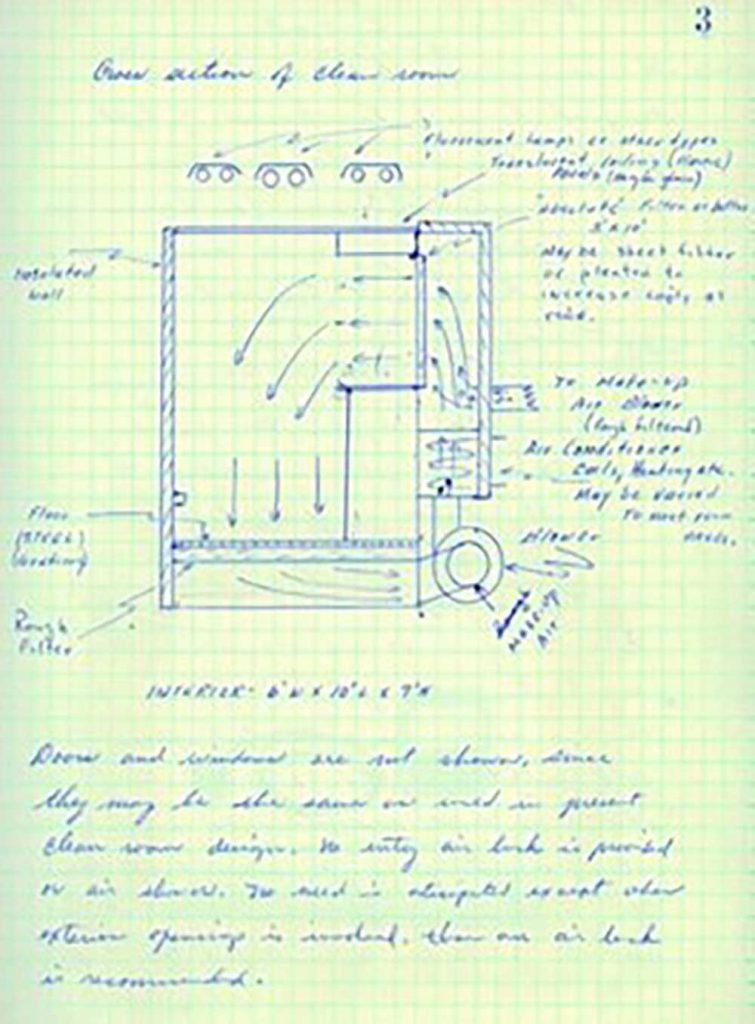

An idea sketched on a tablet

The team spent the next few months traveling to different manufacturers to see the problem firsthand, as well as the clean rooms they had in place at the time. Those clean rooms were not so clean. Tests showed that one of the best clean rooms of that period contained an average of more than a million particles per cubic foot of air.

While driving home from one of those trips, Whitfield had an idea. Whitfield’s son Jim, who was 6 years old at the time, said, “He was on an airplane, and he took out a tablet and basically drew out the entire outline of how the clean room should work.” “It was just a simple sketch. It took just a few minutes, and it’s the basic principle that’s still used today.”

That principle is called laminar-flow, or continuous cleaning of a room with highly filtered air. As Whitfield once said, “It’s letting the wind be the watchman.” The process involves pushing particles onto the floor, filtering them, and recirculating them back into the room with a constant but very slow movement of air. Data collected on Whitfield’s 1961 prototype showed an average of 750 dust particles per cubic foot of air – 1,000 times cleaner than the clean rooms in use at the time.

It was so clear that some people doubted that Whitfield’s data was accurate.

Sandia historian Rebecca Ulrich said, “In the meetings, people questioned the claims. There were people there who had to confirm Whitfield’s credibility.” “Once they realized it was real, the idea spread like wildfire. By the mid-1960s, there were standards in place and various industries adopted the design. It was Sandia’s very first technology transfer. It was transformative.”

The Atomic Energy Commission filed a patent application on the laminar airflow clean room in Whitfield’s name. On November 24, 1964, the US issued Patent No. 3,158,457, titled Ultra Clean Room.

Clean rooms based on Whitfield’s concept are still used today in everything from electronics and pharmaceutical manufacturing to operating and recovery rooms to prevent infection. Early adopters included RCA Corp., General Motors Co., Western Electric Co., Bell Laboratories, and Lovelace Medical Center.

a humble man

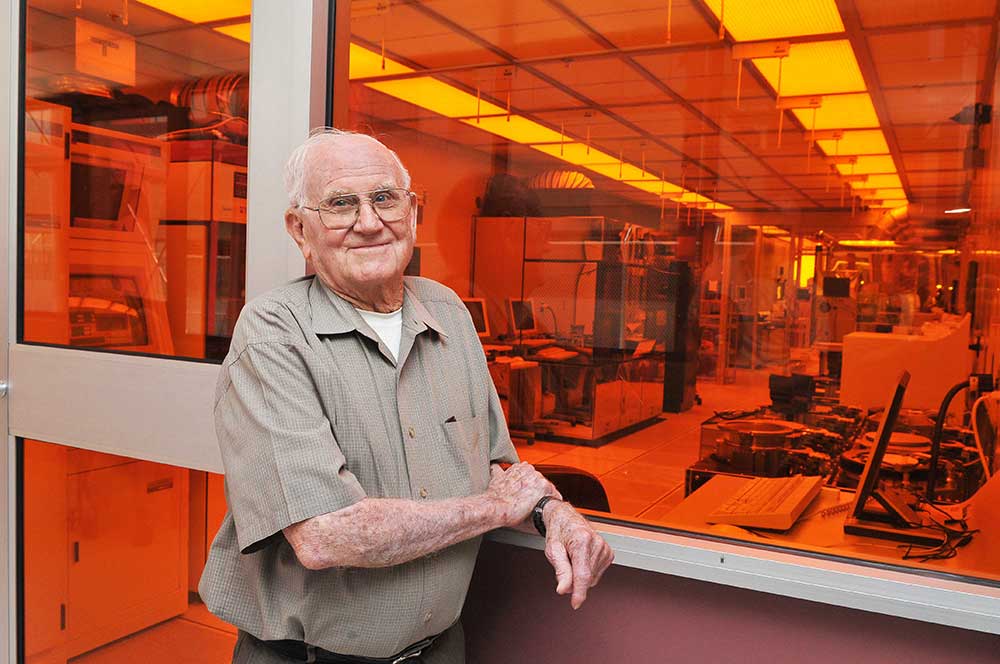

While Whitfield became known as one of Sandia’s historic innovators, he always remained humble.

“I know one of the things he was always insistent about was mentioning the other people involved. He always gave credit to everyone. While the original idea was his, he always talked about the team that helped design, develop and test the concept,” Rebecca said. The team included Claude Marsh, James McDowell, James Mashburn, William Netzel, Irving Codell, Longinos Trujillo, and Harold Baxter.

Whitfield’s son says that when his father invented the clean room he was so young that he did not fully understand what he had accomplished.

“The only thing I remember was that one day my father came home and said to my mother, ‘We got a raise,'” he said. “At that time, this 6-year-old heard the word ‘raisins,’ and I couldn’t quite understand why they were getting so happy with the breakfast food.”

Whitfield said that as he grew up, he saw his father’s influence firsthand.

Whitfield said, “He could take very complex things and boil it down to just the essentials. Being an old farm boy, he would invent something that worked effectively. Even as a kid, a young man, he was like that.”

Jim Whitfield followed in his father’s footsteps and studied physics, mathematics and electrical engineering. He worked for Motorola for 25 years, where he oversaw a clean room. “I actually spent a lot of time working on my father’s inventions. From a personal perspective, I would say to myself ‘I’m working on something my father created.’ Whenever I came in, I’d say, ‘Thanks, Dad.’

Whitfield’s other work

Willis Whitfield worked at Sandia for 30 years. Although the creation of the modern clean room was undoubtedly his greatest achievement, Whitfield also did other important work, such as eliminating sewage by turning it into clean water.

Rebecca said, “This process did not gain much popularity outside the laboratory, but it is an early exploration into energy work and solar energy that Sandia still focuses on today. It is part of the work that Whitfield invented and participated in.”

Later in his career, Whitfield helped NASA develop techniques for sterilizing spacecraft before missions.

honoring a great man

Whitfield died in 2012 at the age of 92, just after his clean room invention celebrated its 50th anniversary. Two years later, in 2014, Whitfield was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame, an honor he shares with the likes of Eli Whitney, Thomas Edison, Orville and Wilbur Wright, Albert Einstein and, most recently, Steve Jobs and John Harvey Kellogg. Whitfield is the only Sandian to date to be honored with a full-size bronze statue. It is located outside Sandia’s Microsystems Engineering, Science and Applications campus where clean rooms are used to manufacture precision mechanical assemblies.

<a href