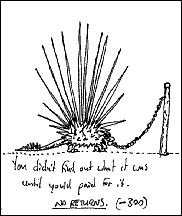

A sample card in the usual 3 by 2.5 inches (7.6 cm × 6.4 cm) US format. A sample card in the usual 3 by 2.5 inches (7.6 cm × 6.4 cm) US format.

|

|

| year active | 1996 to present |

|---|---|

| styles | party game card game Economic |

| player | variable |

| setup time | variable |

| play time | variable |

| Opportunity | variable |

| Skill | cartooning, satire |

1000 blank white cards is a party card game played with cards in which a deck is built as part of the game. Although it is played by adults in organized groups around the world, 1000 Blank White Cards is also said to be suitable for children. rules of hoyle’s games.[1] Since the rules of any game are contained on the cards (rather than being present in the form of ubiquitous rules or in a rule book), 1000 blank white cards can be considered a type of nomogram. It can be played by any number of players and provides the opportunity for card construction and gameplay outside the confines of a single sitting. Creating new cards during the game, dealing with the effects of previous cards, is allowed, and rule modification is encouraged as an integral part of the gameplay.[1][2]

Games include everything that players define by building things and playing. There are no starting rules, and although there may be traditions among certain groups of players, it is in the spirit of the game to protest and condemn these traditions, as well as religiously follow them.

However, for many typical players, the game can be divided into three logical parts: deck building, the game itself, and the epilogue.

A deck of playing cards consists of any number of cards, usually of uniform size and of paper stock stiff enough so that they can be reused. Some may contain artwork, writing, or other game-relevant content created during a previous game, with a fair stock of cards being blank at the beginning of gameplay. It may take some time to create cards before gameplay begins, although card creation can be more dynamic if no advance preparation is done, and it is suggested that the game be simply blitzed to a group of players who may or may not have any idea of what they are getting into. If the game has been played before, all previous cards may be used in gameplay unless the game specifies otherwise, but probably not unless the game allows them to be played.

A typical group’s traditions for deck building are as follows:

Although cards are created all the time throughout the game (except the epilogue), it is necessary to start with at least some pre-generated cards. Despite the name of the game, a deck of 80 to 150 cards is usual, depending on the desired duration of the game, and about half of these will be created before the game begins. If a group does not already have a partial deck they may choose to start with fewer cards and build up most of the deck over the course of the game.

Whether the group already has a deck (from the previous game) or not, they will usually want to add a few more cards, so the first phase of the game involves each player drawing six or seven new cards to add to the deck. Look card structure Below

When the deck is ready, all the cards (including the blanks) are shuffled together and five cards are dealt to each player. The remainder of the deck is placed in the center of the table.

The rules of the game are determined according to the game being played. There is no set order of play or any limit on the length or scope of the game. Such parameters can be set within the game but are of course subject to change.

A sample conference suggests the following:[citation needed]

Play progresses in a clockwise direction, starting with the player to the left of the dealer. On each player’s turn, he draws a card from the central deck and then plays a card from his hand. The card can be played by any player (including the person playing the card) or on the table (so that it has an effect on everyone). Cards with permanent effects, such as awarding points or changing the rules of the game, are placed on the table to remind players of those effects. Cards that have no permanent effect, or cards that have been canceled, are placed in the discard pile.

Blank cards can be turned into playable cards at any time by simply drawing them (see). card structure).

Play continues until there are no cards left in the central deck and no one can play (if they have no cards that can be played in the current position). The “winner” is the player who has the most total points at the end of the game, although in some games the points do not actually matter.

Since the cards created in any given game can be used as the start of a deck for a future game, many players like to trim the deck down to a collection of their favorites. The denouement is an opportunity for the players to collectively decide which cards to keep and which to discard (or set aside as not to be played).

Many players believe that discarding one’s own cards as favorites during the epilogue is a true “win” of the 1000 blank white cards, although the game’s creator has never discarded or destroyed any cards unless that action was specified within the scope of the game. Retaining and replaying cards that seem less than perfect at the moment can help reduce a certain stagnation and tendency to overthink that can otherwise kill the pace of the game.

A group of players in Boston (not long-time Harvard cadre) have come up with the idea of the “suck box”:

We don’t like destroying cards, even if they’re bad, so we have a notecard box called The Sock Box. If a player feels that a card is boring and useless to the gameplay, they will nominate it for entry into The Sock Box. All players present then vote (sometimes pleading their cases), and the cards either go into The Sock Box or remain in the primary deck. Ironically, when The Suck Box was introduced, a player drew a card for the express purpose of adding it to The Suck Box. However, the rest of us thought it was too entertaining a card and had to stay in the deck.[3]

card structure

[edit]

At its simplest, a card is just that: a physical card, which may or may not have any modifications. Its role in the game is as the game itself and any information it contains can be changed, deleted, or modified. Used cards vary widely in size from the original 1+1⁄2-By-3+1⁄2-inch (3.8 cm × 8.9 cm) Wiz-Ed brand flash cards, half or full index cards, just up to an A7 sized sheet of paper. Cards may be created with any numbering medium and are not required to conform to any conventions of size or material unless specified within the scope of the game. Cards have been made from a variety of materials, and it is perfectly acceptable to modify the shape or structure of a card: there is still a card in the original Vis-Aid box, made by Bell Labs developer Microcraft’s Plan 9, to which a tablet of zinc has been affixed with adhesive tape; The card reads “Eat This!… Within a few minutes, the zinc will enter your system.”[2] Many cards have been created that call for their own modification, destruction, or duplication, and many have been created that display nothing more than a picture or text that has no apparent significance. Some have been eaten, burned, or cut and bent into other shapes.

The game falls into structural traditions, a good example of which is the following:

A card contains (usually) a title, a picture, and a description of its effect. The title must uniquely identify the card. The picture can be as simple as a stick figure or as complex as the player prefers. The details, or rules, are the part that affects the game. It can award or deny points, force the player to miss a turn, change the direction of the game, or do anything else the player can think of. The rules written on the cards in the game make up the majority of the total rules of the game.

In practice, these conventions can produce monotonous decks of one-panel cartoons affecting point values, rules, or both. As conceived, sport is far more comprehensive, as it is not inherently limited in length or scope, is fundamentally self-modifying, and may include references to or actual examples of other sports or activities. Games can also encode algorithms (functioning trivially as a Turing machine), store real-world data, and hold or reference non-card objects.

The game was originally created by Nathan McQuillen of Madison, Wisconsin in late 1995.[2][4] He was inspired by seeing a product at a local coffeehouse: a box of 1000 Wis-Aid brand blank white flash cards.[2] He introduced “The Game of 1000 Blank White Cards” to a mixed group including students, improv theater members, and club children a few days later. The early playing sessions were frequent and high-energy, but a fire destroyed the regular venue shortly after play began.[5] The game survived physically, but with the destruction of their regular meeting place, most of the original players lost touch with each other and most soon moved to other cities.

The game began to spread as a meme in the late 1990s through various social networks, mostly collegiate. Former Madison resident Aaron Mandel brought the game to Harvard University and started an active playgroup that changed the size of the cards to more standard half-index dimensions (2+1⁄2 By 3+1⁄2 inches [6.4 cm × 8.9 cm]). Boston players Dave Packer and Stewart King created the first web content representing the game.[2] His graduation helped spread the game further on the west coast and on the web. Subsequently, an article in game Inclusion in the magazine and 2001 revision rules of hoyle’s games[1] Established the game as an independent part of gaming culture. Various celebrities have also contributed cards to the game, including musicians Ben Folds and Jonatha Brooke and cartoonist Bill Plympton.[2]

The game’s inventor and its original players have often expressed joy at the spread of the game, which they mostly considered a brilliant but highly specialized form of conceptual humor that provided them with an excuse to create silly cartoons.[2]

- ^ A b C Hoyle’s Rules of Games, Third Revised and Updated EditionIn material revised by Philip D. Morehead. Penguin Putnam Inc., New York, USA, 2001. ISBN 0-451-20484-0. p. 236-7.

- ^ A b C D E F Yes Fromm, Adam (August 2002). “Drawing the Blank”. game. pp. 7-9.

- ^ “Bob: 1KBWC in Boston”. Archived from the original on 15 July 2006. recovered 7th July, 2006.

- ^ McQuillen, Nathan. “1000 blank white cards”. Archived from the original on 19 September 2000. recovered 30 December, 2013.

- ^ Meg Jones, Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, Monday, February 19, 1996, p. 5 b

<a href